The bard’s in a fix. He’s hit the wall. There he is, only a thousand lines or so into the sweeping war story that will launch Western literature as we know it, and he’s already cracking under the strain.

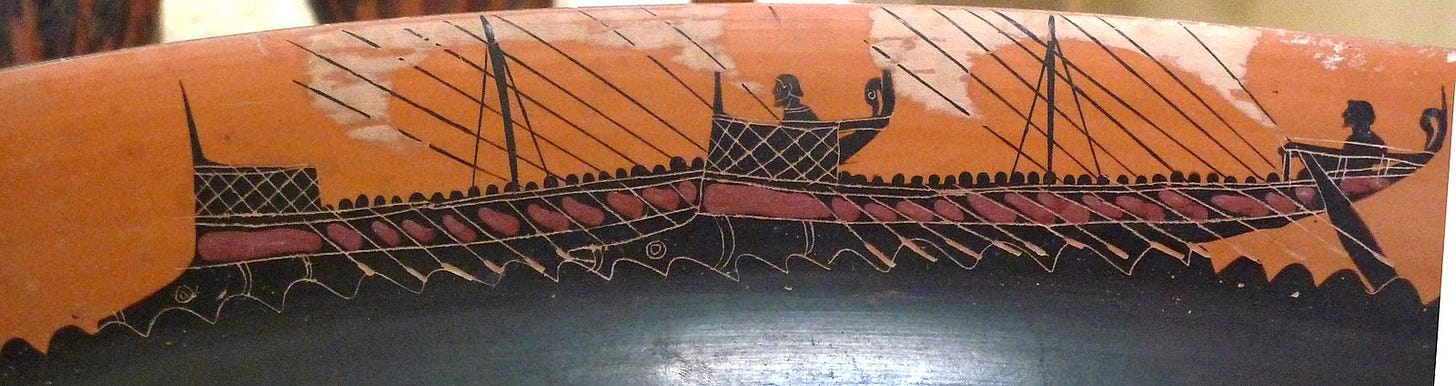

He’s doing his damnedest to conjure up the headspinning immensity of the Greek armada mustering on an unheard-of scale for the assault on Troy, but it’s not working out. The force of heroic simile is not with him. His vaunted gift for metaphor has gone missing.

The monumental poem is just getting started and it’s looking like an epic fail. It’s crunch time for the premier oral poet’s complete and unabridged similes:

The great gathering of armies tribe by farflung tribe in their brazen chain-mail was like nothing so much as a ravening wildfire roaring over the ridges and hilltops.

No, make that like endless wheeling flocks of cranes or swans on the wing, wave after wave and still coming, or like all the shoots and spears and blades in all the fields, making the earth shake.

No, more like swarms of flies in the first days of springtime seething over the shepherds’ stalls when the buckets overflow with milk.

No, no, that still won’t cut it, not by a long shot.

What to do? What he’s always done. He’s got to get the Muses to lend a hand. It’s his first instinct and last resort. Remember, he’s not composing, he’s taking dictation – he’s an instrument, a vessel, a mouthpiece, a go-between. He knows nothing. The Muses know it all. Unless they tell him what to sing, he’s sunk: he could never tally the multitudes by name, not if I had ten tongues and ten mouths, a tireless voice and the heart inside me bronze....

And it’s then he hits on his plan. It’s inspired. Forget the metaphors and the similes, the extravagant figures of speech, the thunderclaps and lightning bolts of protean tropes and conceits. The Muses have given him a better idea.

He will list the ships. He will list them all. He will tick off the fleet ship by ship, sorting out each contingent by its homeland in turn. He will sing of arms and men, and list the captains and kings by name. He will list them all and not miss one. He will list the ships. He will turn an impossible task into a workmanlike job. He will do it with his one tongue. He will list the ships.

The rest is history – and ages of drudgery. The socalled “Catalogue of Ships” in Book II of The Iliad may have no rival as the most renowned literary list of all time – “the model list par excellence,” as uber-polymath Umberto Eco would have it – but it’s also gone down as the longest and hardest slog of them all. Clocking in at over 250 lines and rattling off somewhere in the vicinity of 200 place names, it’s as punishing a passage of ancient poetry as a modern reader can try to soldier through, and its casualties are legion. Depending on which commentaries you’re consulting, informed opinion seems about evenly split between those who bellyache that it’s remorselessly unreadable and those who bemoan that it’s positively unendurable.

This reputation for epic tedium naturally puts the acolyte of lists in a tight spot. If the grand-daddy of them all leaves such flailing in its wake, how to defend the bedrock aesthetics of the thing? And it’s not just the mayfly attention span of the mass-media age that makes the Homeric shipping news such hard going. As Francis Spufford reminds us in the introduction to his 1989 anthology The Chatto Book of Cabbages and Kings: Lists in Literature, no less an Augustan than Alexander Pope harbored similar misgivings way back when was proffering his translation of The Iliad to a presumably more classically savvy reading public. The snippet Spufford quotes from Pope’s notes hardly seems to have passed its expiration date in getting to the nub of the problem:

I had some cause to fear that this Catalogue which contributed so much to the Success of the Author, should ruin that of the translator. A meer heap of Proper names tho’ but for a few lines together, could afford little Entertainment to an English reader, who probably could not be appriz’d either of the Necessity or Beauty of this Part of the Poem.

Spufford pounces like a cat on that “meer heap,” remarking that Pope’s lengthy apologia for keeping the heap intact “only claims compensations for something he assumes to be, at root, inexplicably dull.” All the same, there are those who evidently wouldn’t want it a ship shorter. For classicist and critic Daniel Mendelsohn, the Catalogue of Ships is “a prodigious history lesson” that teleports us back to the heyday of the Homeridae rhapsodes: “the sheer recitation of it must have been an astonishing tour de force in performance—epic poetry’s answer to CinemaScope.”

The staunchest scholarly supporters of the Catalogue as explicably enlightening tend to defend its demands on the same general terms, above all for the light it shines on the fossil record of the oral epic tradition. Far from an interlude of mind-numbing monotony, we’re assured, it’s a mesmerizing master class in the ancient arts of memory, the proceedings made possible by Mnemoysene Herself, the one and only mother of the muses.

Going by the expert testimony, the logjam of names turns out to be a mental filing system like none other. It’s an archive, a dossier, a roster, a rolodex, a Mycenean Who’s Who, even a Bronze Age GPS. As Homeric classicist Jenny Strauss Clay argues in her 2011 book Homer’s Trojan Theater, “Homer was able to recite the Catalogue by creating a mental journey that used the mnemonic techniques involving loci or places.... By envisioning a series of places, Homer could mentally walk – or sail – through Greece and produce a detailed catalogue.” And now you can too: the University of Virginia hosts a website built on Clay’s research called “Mapping the Catalogue of Ships” that aims to show how Homer’s rhapsodic cartography holds up with uncanny accuracy down to the last shipping manifest.

Umberto Eco is having none of it. He relishes the long march through the ships on completely different grounds. In The Infinity of Lists, his sumptuous historical survey of listmaking in Western art and literature, he begins by drawing a categorical distinction between the Catalogue of Ships and another celebrated passage much later in the Iliad, the magnificent bespoke shield Hephaestus forges for Achilles in the smithy of the gods. In the latter, claims Eco, we see “the epiphany of Form,” an aesthetic representation of “harmonious completion and closure.” The Catalogue of Ships confronts us with something else altogether: a full-scale figurative model of that which is innumerable and interminable, fearfully incomplete and openended, too vast to grasp either rationally or imaginatively. One mode invokes order; the other induces vertigo. Eco doesn’t pit one against the other so much as posit that culture by its nature toggles between their alternating currents. By his lights it’s been that way ever since the rosy-fingered dawn of Western Civ, pointing out that “already in Homer it seems that there is a swing between a poetics of ‘everything included’ and a poetics of the ‘etcetera.’ ”

Eco’s own allegiances could not be more clear. He adores the “etcetera,” he’s crazy about the incalculable, he’s ensorcelled by infinitude. He can’t get enough of “the rhetoric of enumeration” and the depiction of “coherent excess.” Give him ships, ships, and more ships. All of which explains why he’s enthralled by lists in all the ingenious and promiscuous forms lists take – he regards them as the indefatigable poetic expression of anything and everything that’s inexpressibly inexhaustible. He especially prizes the Catalogue of Ships as the prototype for the “topos of ineffability” that he sees as the catalyst for so many lists that followed in its wake:

Faced with something that is immensely large, or unknown, of which we still do not know enough or of which we shall never know, the author tells us he is unable to say, and so he proposes a list very often as a specimen, example, or indication, leaving the reader to imagine the rest.

You could pick a quarrel as to whether “this Part of the Poem” meets all the specs for ineffability on that score. Presumably the number of ships and captains is finite, and it wouldn’t be sporting for Mother Memory to let him leave any out. But if it’s possible to carp over the vagaries of any particular list on Eco’s docket, the preponderance of the evidence breaks down just about all resistance to his argument in toto. In reaching back to the Iliad for “the model list par excellence” and the foundational text for “the poetics of etcetera,” he gives the reader leave to imagine how the utilitarian list and the fantastical list might have parted ways from the start, thereby giving rise to a time-tested method of conducting raids on the incomprehensible.

Muse on it for a spell, and in the holds of those ships you can all but picture the infinity of literary lists to come – the lists of deep dark forest trees in Ovid, Chaucer, and Spenser; the lists of virtues and vices from Dante on down; the Aeneid’s list of Italian war heroes and Paradise Lost’s list of fallen angels; the list-happy tavern songs of the Carmina Burana and Villon’s blacklist mock testaments; the litanies on things sacred and profane in the pages of Dunbar and Nashe and Donne and Herbert and Herrick and Smart; the ludic playlists of major modern listophiliacs like Stein and Moore and Auden; the great all-out full-tilt American whistle-stop list that is Leaves of Grass, etcetera, etcetera.

Of the making of lists there is no ending, and it’s been like that from the beginning. Ships, ships, and more ships.

From a running series of takes on the poetics of lists

[Previously]

Got a Little List: Funny Business

https://postcardsfromthevolcano.substack.com/p/got-a-little-list