“I’ve got a little list — I’ve got a little list!” crows the Lord High Executioner, and the chorus eggs him on. As well they might – there’s no cheap thrill quite so fiendishly enticing as a hit list, a shit list, a list of those who’ll “none of ‘em be missed.” From the moment Ko-Ko the tailor first belted out his maniacal patter-song as the new sheriff in town midway through the first act of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado, the little list has taken on a life of its own, making fresh mince-meat out of an endless supply of “society offenders who might be underground” and spawning meta-lampoons by the score that go after one jugular after another.

By longstanding custom, Ko-Ko updates his little list with most every revival since that first run in 1885, supplanting the benighted “banjo serenader” and “that singular anomaly, the lady novelist” with any number of newly hatched boors, louts, twits, churls, creeps, and dolts. The ink had hardly dried on his ur-spoof when the sporting W. S. Gilbert himself sent up his own handiwork in style, merrily blackballing another batch of insufferables including “those who hold the principle, unalterably fixed, / That instruction with amusement should most carefully be mixed” and, of course, “All narrow-minded people who are stingy with their jam.” The list gets longer. The heads keep rolling. The chorus never flags.

Lists are funny that way. Lists are funny, period. The art of the list may have been born in deadly earnest and come up in the world by dint of due diligence, but somewhere along the line the spirit of the thing was shanghaied by the Lords of Misrule and we’ve been cracking wise and kicking against the pricks with it ever since. Once a list gets rolling it doesn’t take long before it’s barrelling off in the general direction of travesty and absurdity, no matter what course it might be charting. Getting there in one piece just depends on the hand at the throttle. For the bureaucrat and the quant, a list is a list and nothing but a list. For the jester and the wag, a list is nothing less than one of the great running gags going, a gift that keeps on giving.

Any doubts on the matter can be pretty much laid to rest by taking in the riotous carnival that is the chapter “Comic Elaborations” in Francis Spufford’s boffo anthology of literary lists, Cabbages and Kings. The star of the show is Rabelais, whose riproaring fun and games with lists in Gargantua and Pantagruel inaugurates a saturnalian tradition of listing that Spufford sees running through the pages of Sterne, Joyce, and Beckett with a vengeance. Never mind that these giants of the genre plied their trade in the precincts of prose: what gave the Rabelaisian list its boundless sphere of influence, Spufford argues, was its breakthrough imaginative premise that “you could make the rules of a discipline your playground, in rather the same way nonsense poetry does.” But he also sensibly acknowledges that there’s a more down-to-earth explanation for the revolutionary lunacy of Rabelais’s hyperkinetic listmaking: “Well-judged excess is always funny.”

To judge by the specimens on display in “Comic Elaborations,” there’s another funny thing about the masquerades of listing: more often than not, its harlequins turn out to be armed and dangerous. The more excessively elaborate the list, the more it takes on an aura of animus and air of malice, as if on a mission to administer the coup de grace by a thousand cuts. Tacitly acknowledging as much, Spufford makes a point of fencing off what he deems to be the most nakedly rancorous animadversions under the chapter heading “Hostilities: Polemic, Satire, Abuse,” and that’s where you’ll find “The Lord High Executioner’s Song” baring its fangs.

But the effort to draw a bright line between levels of militancy and degrees of toxicity in the deployment of lists seems at bottom quixotic. By what unit of measure is Koko’s little list demonstrably nastier than the Earl of Rochester’s finely distilled witches’ brew of ethnic slurs near the end of “Upon Nothing”? (“French Truth, Dutch Prowess, British Policy, / Hybernian Learning, Scotch Civility, / Spaniards’ Dispatch, Danes’ Wit, are mainly seen in thee.”) What are Rabelais’s double-column lineup of breeds of fools (“Kitchen-haunting f. ; “Beetle-headed f.) and his rundown of “the inward Parts of Shrovetide” (“His Notions, like Snails crawling out of Strawberries ... His Judgment, like a Shoing-horn”) if not patently abusive to the core? Polemic, Satire, Abuse, Farce, Burlesque, Parody, Obloquy, Ridicule, Caricature, Invective, Shtick, the Putdown, the Comeback, the Jape, the Affront, the Taunt – such is the stuff that the lustiest of lists are made on.

Those sharp edges and raised hackles may be one of the surest ways to tell a poetic list apart from all the rest. As the Chaucer scholar Stephen Barney notes, “That genre in which gargantuan excesses of vice find their counterpart in a surfeited language of abused plentitude is satire. As satire magnifies and deals in ‘disorderly profusion,’ it naturally uses lists.” That’s not to say that there’s no such thing as an artful list in earnest. It simply means that a stellar hit list, a scintillating shit list, a blacklist possessed, has a special place in the heart of the diehard satirist. If you want to push it, you might want to place a small bet that there’s a little Lord High Executioner with a little list in all of us.

A quick online keyword search of “I’ve Got a Little List” also turns up a puckish think piece of that title by William Gass, dating back to the cusp of the millennium when e-mail “list-servs” were breaking out all over. It’s not to be missed. What mainly seems to tickle Gass’s fancy is the primordial tug of war between hierarchy and anarchy he discerns throughout the checkered cultural history of listing, stirring up all kinds of funny business along the way. On one side are the lists that rank and rate and discriminate; on the other the ones that mean to make a mockery of their opposite numbers. Gass doesn’t hide his allegiances to the dissident faction, but it’s the shifty metaphysics rather than the wonky mechanics of lists that really wind him up. For anyone with a dog in the fight, that’s also where the real action is. If lists can be literary in their own right, they can’t be literary all on their own. There has to be an organizing principle on the line. The true nature of the list has to be in dispute. The proof of the pudding is in the push and pull.

That doesn’t stop Gass from getting off some of his choicest darts and digs in defense of the renegade list, the libertine list, the list on the loose. Do you think of the list as above all else a systematic idea of order? Think again: “The list is the fundamental rhetorical form for creating a sense of abundance, overflow, excess.” Are you nodding at the notion that a list must be as dry as dust and boast about as much artistic sensibility as bubble-wrap? Wake up: “Lists are juxtapositions, and exhibit many of the qualities of collage.” Isn’t the list ideal for charting who’s up and who’s down in the great chain of being? On the contrary: “Normally lists are the purposeful coming together of names like starlings to their evening trees. They tend to confer equality on their members, also like starlings to their evening trees.” Aren’t lists the antithesis of all that’s democratic and egalitarian? Not on your life: “The thousand and three ladies on Don Giovanni’s were each equally enjoyed, the list presumes, all equally loved.”

Then there’s Lord High Executioner’s little list itself, a cheeky little monument to wishful listing that by now has become something of its own term of art. Ever the kibitzer, Gass plumps to have it classified as a canonic example of a “maybe, maybe” list that oftentimes pokes fun at its own facetious futility. “Since most of these ‘maybes’ are ‘never, nevers,’ ” he remarks, “ it should be clear that some lists are actually counterfactual, like daydreams, and require the subjunctive.”

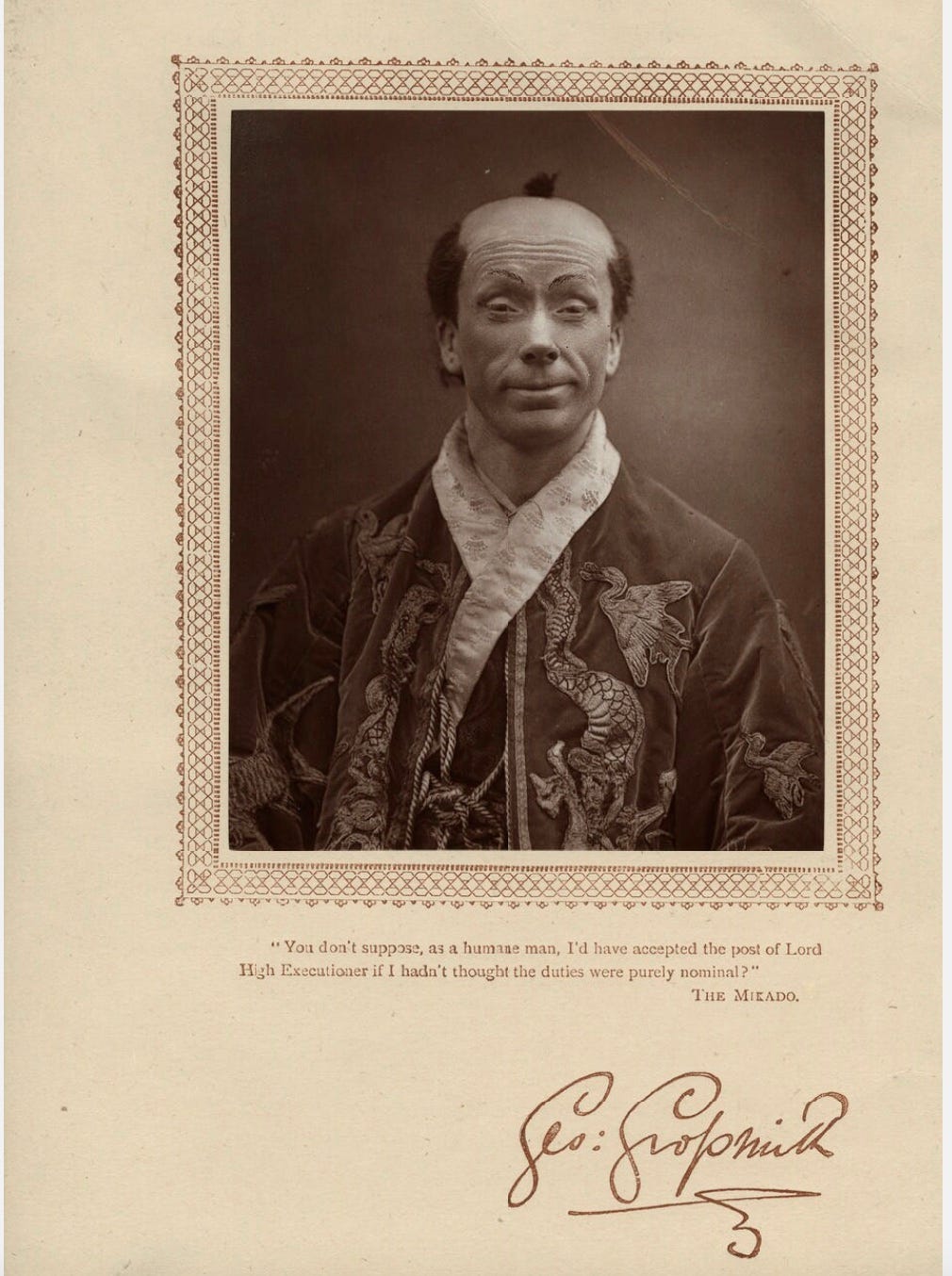

That would help explain the perennial charms of KoKo’s delirious countdown of those who never would be missed, not to mention its nine lives and then some as a pet cheat-sheet for remixed lists of presumptive goners. The English baritone Richard Suart, a frequently cast KoKo from way back, has seen fit to co-author a whole anthology of little-list parodies old and new, cataloguing the legions that such brazen daydreamers as George (Diary of a Nobody) Grossmith, Groucho Marx, and Eric Idle would dispatch in a trice.

Even in that heady company, there’s one that belongs at the top of any all-time list of little lists. That would be John Hollander’s pitch-perfect riposte to the breaking news of Nixon’s Enemies List, printed in the July 16, 1973 issue of New York Magazine alongside a David Levine sketch of a scowling Tricky Dick sporting a samurai tonsure and topknot. He’s got a little list, John Dean had testified at the Watergate hearings a few weeks earlier, and thanks to Hollander’s quick feet, now so did we:

Of the prominent and distinguished who have made poor Nixon cross

He’s got a little list, he’s got a little list –

Writers, businessmen and actors unadoring of the Boss

Adorn his litle list, and they really would be missed;

And therefore to be fair we’ve drawn a list up of our own,

Of Enemies both far and near the Presidential Throne –

From the giddy little Liddy and the Honorable Hunt

And the unemployed ex-Cubans who performed their cheesy stunt

To the gang of loyal lawyers who, despite (we must insist)

Their great deeds for God and Country, will never quite be missed.

We’ve got ‘em on the list – we’ve got ‘em on the list,

And they’ll none of them be missed – they’ll none of ‘em be missed.

Not exactly a fair fight, this asymmetrical battle of the lists, and not just because the poet’s dexterity handily takes the measure of the president’s duplicity. A humorless literal list doesn’t stand a chance against a counterfactual list in jest in the long run, especially when the sham assumes the belittling form of a slapstick shit-list calling out a self-righteous dumbass hit-list as ludicrous.

Even so, the list that’s in it for laughs needs the list that’s on the level to make its day, or else there soon won’t be anything left on its bucket list. Maybe then they’re best described as frenemies – the literal list and the literary list, the imperative list and the subjunctive list, the workhorse list and the waspish list, the straight-faced list and the tongue-in-cheek list, the forced march of a list and the wild goose chase of a list, the lockstep list and the larksome list, the buttoned-up list and the list unzipped.

The little list goes on. The chorus never stops. Lists are funny that way.

Sources

Stephen A. Barney, “Chaucer’s Lists.” In The Wisdom of Poetry: Essays in Early English Literature in Honor of Morton W. Bloomfield. Western Michigan University Press, Medieval Institute (1982)

Umberto Eco, The Infinity of Lists from Homer to Joyce. MacLehose Press (2009)

William Gass, “I’ve Got a Little List.” Salmagundi, (1996). Reprinted in Tests of Time. Knopf (2002)

John Hollander, “We’ve Got a Little List.” New York Magazine (16 July 1973)

François Rabelais, Gargantua & Pantagruel. Translated into English by Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty & Peter Antony Motteux. Gutenberg Editions (2004).

Francis Spufford, ed. The Chatto Book of Cabbages and Kings: Lists in Literature. Chatto & Windus (1989)

Richard Suart and A. S. H. Smythe, They’d None of ‘em Be Missed. Pallas Athene (2023)