A curated lunar roster of songs and poems all about the Moon. Lines and lyrics about the Moon or to the Moon, our one and only. The Moon in all its phases and guises, lauded by poets and troubadours the world over. My own annotated playlist of poems and songs for a fantasy lunar payload, just for fun. A vanity project, like all the off-world archives already up there. The Moon is on the Watchlist, and there’s no time to lose.

Shoot the Moon: The Lunar Library Has Landed [LINK]

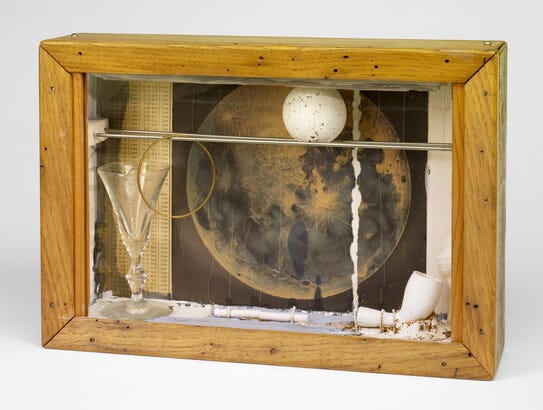

Note on art: All images from Joseph Cornell’s Soap Bubble Set series, shadowboxes often containing moon maps or “lunar-space objects.” Complete list of catalogue credits at the end of the post.

“Midnight Poem” | Attributed to Sappho

A fragment. Title made-up. A fragment of lyric poetry about the moon, the moon going down at midnight. By long tradition, attributed to Sappho, the ancient Greek poetess Plato crowned The Tenth Muse. “I am convinced that the first lyric poem was written at night,” writes Mary Ruefle in her 2012 essay “Poetry and the Moon” (Madness, Rack, and Honey), “and that the moon was witness to the event and that the event was witness to the moon…. In the West, lyric poetry begins with a woman on an island in the seventh or sixth century BC, and I say now: lyric poetry begins with a woman on an island on a moonlit night, when the moon is nearing full or just the other side of it, or on the dot.” Sounds just about right. There are many translations of the moon fragment in English, but you can’t go wrong with the versions in Mary Barnard’s Sappho: A New Translation (1958) and Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho (2002). And get this: In 2016 a team of scientists reported in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage that a custom software program for plotting the movements of celestial bodies through history had projected that the poem may have been written on a starry night over the Greek island of Lesbos in 570 BCE sometime between January 25 and March 31. According to the report, the estimate confirmed the longstanding conjecture that the poem was “composed in late winter/early spring, a time frame that is not unusual for lyrics of an amorous nature.”

Li Po (Li Bai) | “Drinking Alone Under the Moon”

Legend has it that the storied T’ang Dynasty poet Li Po (701-762) perished by drowning when he fell out of his boat attempting to embrace the moon’s reflection in the river. On the strength of this drunken moonlit reverie translated by many hands, it might just be true.

Sir Philip Sidney | Astrophil and Stella 31 “With how sad steps, O Moon, thou climb’st the skies”

A celebrated sonnet from Sidney’s celebrated sonnet sequence written around 1582, poems of unrequited love cast in the persona of a “Star-lover” fruitlessly wooing his “Star.” Begins by buttonholing the rising moon as a fellow-sufferer of lovesickness (“how wan a face!”), then rattles off a succession of beseeching rhetorical questions (“O Moon! tell me…”) asking why on earth the heavens have decreed that “lovers scorn whom that love doth possess.” A lament so potent it would go on to spawn moony copycat poems by William Wordsworth and Philip Larkin.

“Au Clair de la Lune” | Trad. French

Traditional French folk song of unknown origin, the tune often attributed to Baroque composer Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687). Best-known as a popular French children’s song often crooned as a lullaby, with lyrics featuring the fabled commedia dell’ arte characters Harlequin and Pierrot. In English, usually translated “In the Moonlight” or “By the Light of the Moon.” Not to be confused with Claude Debussy’s familiar 1905 piano composition “Clair de Lune,” based on Paul Verlaine’s poem of that name from 1869. An evergreen ditty making musical history in 2008, thanks to the discovery of the surviving cylinders for a “phonautograph” made by French inventor Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville in 1860 that stands by no small margin as the earliest sound recording of a human voice, some ghostly unknown singer warbling the opening bars of “Au Claire de la Lune.”

“Hey Diddle Diddle” | Mother Goose’s Melody

You’ve known it forever – The cow jumped over the moon. A classic nursery rhyme from way back. Earliest appearance in print: Mother Goose’s Melody, brought out by pioneering children’s publisher John Newbery, London, circa 1765. Hey diddle diddle, | The cat and the fiddle, | The cow jumped over the moon… Pure unadulterated nonsense? A daffy jingle for nippers? All that and more, according to GK Chesterton. “It is a masterpiece of psychology, a classic and perfect model of education,” the great English scribe declares in his tart 1921 essay “Child Psychology and Nonsense.” He’s not just yanking your chain: “The cow jumping over the moon is not only a fancy very suitable to children, it is a theme very worthy of poets. The lunar adventure may appear to some a lunatic adventure, but it is one round which the imagination of man has always revolved…”

Giacomo Leopardi | “Alla Luna” (“To the Moon”)

A melancholy mash note to the Moon by the moon-smitten Italian poet Leopardi (1798-1837), from his landmark collection of lyric poetry Canti (1835). In “Poet of Problems,” the introduction to his 2011 annotated translation of Leopardi’s masterwork, Jonathan Galassi observes that the moon is adduced or addressed in fourteen of the forty-one poems in the Canti. That’s a strong dose of moonlight, and it was more than a Romantic obsession. As Italo Calvino noted in Six Memos for the Next Millennium (1988), the wunderkind Leopardi wrote “an amazingly erudite History of Astronomy” at age 15 and knew whereof he rhapsodized. Leopardi’s passion for the moon epitomizes for Calvino the literary essence of “Lightness”: “As soon as the moon appears in poetry, it brings with it a sensation of lightness, suspension, a silent calm enchantment. When I began thinking about these lectures, I wanted to devote one whole talk to the moon, to trace its apparitions in the literatures of many times and places. Then I decided that the moon should be left entirely to Leopardi.”

John Keegan Casey | “The Rising of the Moon”

Irish rebel ballad commemorating the failed Rising of 1798 led by the revolutionary Wolfe Tone’s United Irishmen. Title track on the 1961 album by the Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem, The Rising of the Moon: Irish Songs of Rebellion. From the liner notes:

While people were waiting for the 1798 rising, pikes and guns were hidden in thatch and bogs, and hearts were beating fast. Sixty years after the rising, John Keegan Casey wrote this song while in prison as a Fenian; he died in prison at the tender age of twenty-three as a result of his sufferings. The phrase “The rising of the moon” has become almost proverbial in connection with an Irish uprising in arms. The air is well-known as “The Wearing of the Green.”

A popular broadside ballad in circulation since 1865, and still in rotation today via recordings by Irish and American folksingers. Not be to missed: the amped-up version by Shane MacGowan and the Popes from 1994.

Percy Bysshe Shelley | “The Waning Moon” & “To the Moon”

Two postage-stamp lyric poems, the latter longer one a fragment trailing an ellipsis. Light-years away from Shelley’s best stuff, but worth a glance as fitful High Romantic high signs to “Thou chosen sister of the Spirit.”

Jules Laforgue | Complainte de la lune en province (“Complaint of the Moon in the Provinces”)

Just one of the many moon poems composed in the short life of French phenom Jules Laforgue (1860-1887), a perennial candidate for most moonstruck poet of them all. He wasn’t shy about it either, introducing his 1886 book The Imitation of Our Lady the Moon as “a contribution to the cult of the moon.” In Selected Writings of Jules Laforgue, the poet and translator William Jay Smith makes it sound like the opus took the cult to new heights: “The book is composed as a lunar manual with a preamble of disgust and dismissal addressed to the sun, litanies of the first quarter of the moon, and a description of lunar flora and fauna. The full moon is celebrated by a ‘decameron of pierrots,’ and there ensues a consideration of various lunar manifestations – ‘surrogates for the moon during the day’ – and litanies of the last quarter of the moon.” If you’re not up for all that, “The Complaint of the Moon in the Provinces” (from Laforgue’s dashing earlier collection Les Complaintes) is just the thing for a good quick hit – a piquant comic aria in fifteen punchy couplets that leaves you wanting more. If the opening couplet touches a sure nerve all by itself, consider yourself initiated into the cult: “Ah, the lovely full Moon, | As big as a fortune!”

Robert Louis Stevenson | “The Moon”

Verse XXXII in A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885), not one of the perennial faves like “My Shadow” or “The Land of Counterpane,” but reliably rife with pithy charm and eldritch zing. Hits the sweet spot right in between the earthy and the ethereal.

One of the earliest and shiniest Tin Pan Alley moon numbers, debuted by the married vaudevilleans Nora Bayes and Jack Norworth for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1908. Ruth Etting recorded the tune for the Ziegfeld Follies of 1931.

“By the Light of the Silvery Moon”

By the light of the silvery moon | I want to spoon | To my honey, I'll croon love’s tune |Honeymoon, keep a-shinin’ in June

Another early and surely the most silvery Tin Pan Alley moon number, written in 1909 by composer Gus Edwards and lyricist Edward Madden. Notable recordings by Ada Jones (c. 1910), Fats Waller (1942), Little Richard (1960), and Julie Andrews (1962). Fixed in the pop firmament by Doris Day’s in the 1953 movie of the same name.

WB Yeats | “Adam’s Curse”

Where to begin with Yeats and the moon? Will it ever come to an end? For Yeats in later life, the moon wasn’t just the moon. It was a vision. Make that A Vision, the vertiginous treatise on occult mysticism first published in 1925. The book expounded an impenetrable system of universal correspondences governing historical cycles and individual lives, all in sync with the phases of the moon. Yeats embarked on the all-consuming project in October 1917 in concert with his new wife Georgie Hyde-Lees, spurred by her rapt experiments in channeling esoteric knowledge from the spirit world through “automatic writing.” Poems wrapped up in the moon’s secret powers would follow suit: “The Phases of the Moon” and “The Cat and the Moon” in the 1918 collection The Wild Swans at Coole, along with pieces of dramatic verse like “The Crazed Moon,” “Blood and the Moon,” and the title poem of the late collection A Full Moon in March. Is it all sheer lunacy, full stop? Your call, but for my money Yeats’s most sublime moon poem has to be “Adam’s Curse,” dating back to 1903, a lapidary vignette of companions who “talked of poetry” upon a late summer’s evening. Spoiler alert: the moon makes a late appearance with no fanfare, “worn as if it had been a shell | Washed by time’s waters as they rose and fell…” Leaving one pressing question: why wouldn’t the older Yeats take his wife’s chatty shades at their word? In his introduction to A Vision he tells of how in the first throes of Georgie’s auto-dictations he asked her to relay a message to the spirits. The poet was more than ready to “spend what remained of life explaining and piecing together those scattered sentences” so that all would be revealed. “No, was the answer, we have come to give you metaphors for poetry.”

Blue moon, you saw me standing alone | Without a dream in my heart | Without a love of my own…

The great Rodgers & Hart number for MGM (1934) that might just outshine them all. Recorded by just about everyone from Billie Holiday and Frank Sinatra to Sam Cooke and Cyndi Lauper. Crossover hit for Elvis in 1956. Sneaky-good countrified cover for Dylan on 1970 double album Self Portrait.

Blue moon of Kentucky, keep on shining

Shine on the one that's gone and left me blue

Writer: bluegrass colossus Bill Monroe. First recorded with his backing band The Bluegrass Boys in 1946. Elvis covered this one too, in an uptempo rockabilly version as the B-side of his maiden Sun Records release “That’s Alright” in 1954.

Mina Loy | “Lunar Baedeker”

A moonwalk on the wild side – sci-fi meets dada meets acid trip. Lucifer spooning out coke to somnambulists, spotlit backdrops of Necropolis and Lethe and Pharoah’s tombs, “onyx-eyed Odalisques” and “posthumous parvenues” on the make in a multisyllabic demimonde of “Delirious Avenues” and “mercurial doomsdays.” Title poem of Mina (don’t call her Myrna) Loy’s 1923 first poetry collection, calculated to discombobulate. A Grand Tour of the Moon (Baedekers were the name-brand travel guides of the day) staged as an in-your-face mashup of surrealist satire and avant-garde glossolalia. The man in the moon is still wondering what hit him.

Wallace Stevens | “Lunar Paraphrase”

As billed, on both counts. The moon in paraphrase, a distillation of lunar aura. First line: “The moon is the mother of pathos and pity.” Last line: “The moon is the mother of pathos and pity.” The ten-line stanza in between – one serpentine complex-compound sentence phrase by phrase unveiling “a golden illusion” – becomes the center of gravity for the poem’s complete metaphorical orbit.

Federico García Lorca, Romance de la Luna, Luna (“Ballad of the Moon Moon”)

Moon crosses the sky | With a boy by the hand…

First of the eighteen poems in García Lorca’s breakthrough 1928 book Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads), all constellating around traditional gitano life and lore in Lorca’s native Andalusia. In García Lorca’s own words, “A book that hardly expresses visible Andalusia at all, but where the hidden Andalusia trembles.” Aficionados say that the word la luna appears more than 200 times in the Romancero. See also: Viaje a la Luna (Trip to the Moon), the poet’s 1929 screenplay that was made into a short film by Catalan director Frederic Amat for García Lorca’s centenary in 1998.

You say it’s only a paper moon | Sailing over a cardboard sea | But it wouldn't be make-believe | if you believed in me

Music by Harold Arlen, lyrics by Yip Harburg & Billy Rose (1933). Original title: “If You Believed in Me.” Hit recordings by Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole, and the reprises never stop. Latest hot version: beabadoobee on the soundtrack for the 2024 first season of Apple-TV series The New Look.

“What a Little Moonlight Can Do”

Ooh, ooh, ooh |What a little moonlight can do | Ooh, ooh, ooh | What a little moonlight can do to you

Composer: Harry M. Woods (1934). Scads of renditions, but it all comes down to Billie Holiday and everyone else.

Somewhere there’s music | How faint the tune | Somewhere there’s heaven |How high the moon

Lyrics: Nancy Hamilton. Music: Morgan Lewis. Broadway standard from Two for the Show (1940). Famous home recording by Les Paul and Mary Ford in 1951 spent nine weeks at the top of the Billboard chart. Most famous take of them all: penultimate track on Ella Fitzgerald’s 1960 live album Ella in Berlin, 6:58 of regal swinging and scatting.

It’s that old devil moon | That you stole from the skies | It’s that old devil moon in your eyes

Composed by Burton Lane. Lyrics by Yip Harburg. Written for the original 1947 production of the musical Finian’s Rainbow. All-world version: Frank Sinatra on his all-world 1956 LP Songs for Swingin’ Lovers. Schmaltz-tacular version: Duet by Don Francks & Petula Clark for the 1968 movie adaptation of Finian’s Rainbow.

Fly me to the moon | Let me play among the stars | Let me see what spring is like on a-Jupiter and Mars

Songwriter: Bart Howard. Original title: “In Other Words (Fly Me to the Moon).” First recording: Kaye Ballard (1954). Iconic recording: Frank Sinatra with Count Basie & His Orchestra, conducted by Quincy Jones (1964). Personal favorite: Astrud Gilberto (1964).

Robert Hayden | “Full Moon”

Presciently moody elegy for the untrodden Moon circa 1962, when the lunar landing was still a twinkle in NASA’s eye. The Sixties scarcely underway, and already the poet has started the countdown — the full moon “No longer throne of a goddess to whom we pray…. and tomorrow perhaps an arms base.”

May Swenson | “Landing on the Moon”

Dare we land upon a dream? Another poem dating from the early days of the NASA lunar mission, metaphysical powers locked in a tug-of-war with technological prowess.

Creedence Clearwater Revival | “Bad Moon Rising” (1969)

I see the bad moon arising, | I see trouble on the way | I see earthquakes and lightnin’ | I see bad times today

Lead single from the album Green River. Recorded in March 1969, but with no apparent connection to the upcoming Apollo 11 mission. Songwriter John Fogerty allegedly wrote it after watching the 1941 movie The Devil and Daniel Webster, based on Pulitzer-winning poet Stephen Vincent Benét’s 1936 short story.

Van Morrison | “Moondance” (1970)

Jazzy title cut from Morrison’s third studio album, written while Belfast-born “Van the Man” was living in Cambridge, MA. Link version: “Moondance” live from the doc Too Late to Stop Now (1974), a mix of shows Morrison’s 1973 tour with his eleven-piece band, the Caledonia Soul Orchestra.

Philip Larkin | “Sad Steps”

A shout-out to Sir Philip Sidney’s iconic sonnet, one Philip to another across the chasm of four hundred years. Title cues up the plaintive original (“With how sad steps, O Moon…”); first line kicks off the jaded rejoinder (“Groping back to bed after a piss”). But it’s no crude take-down: even as Larkin’s post-loo moongazing takes the piss out of courtly lunar sentiment (“Lozenge of love! Medallion of art!”), the measured reflective tenor prompted by “looking up there” at the moon’s “wide stare” elicits an austere yet genuinely moving epiphany. Larkin at his most ineluctably Larkinesque.

The Police | “Walking on the Moon”

Giant steps are what you take | Walking on the moon | I hope my leg don't break | Walking on the moon

Composer: Sting (Gordon Sumner). Loping reggae-esque number from the band’s second album Reggatta De Blanc (1979). Official video shot at Kennedy Space Center in Florida (23 Oct 1979).

REM | “Man on the Moon”

If you believed they put a man on the moon | (Man on the moon) | If you believe there's nothing up his sleeve | Then nothing is cool (nothing)

From Automatic for the People (1992). Michael Stipe’s tribute to renegade comedian Andy Kaufman (1949-1984), referencing conspiracy theories that the moon landing was faked as a nod towards the conspiracy theory that Kaufman faked his own death. Song adopted as title of the 1999 Andy Kaufman biopic directed by Miloš Forman and starring Jim Carrey.

One Giant Leap | 20 July 1969

Special category: Occasional verse on the Apollo 11 touchdown and moonwalk, along with the occasional epigrammatic aperçu. Caveat: most of it hasn’t aged well. To the extent that things in this general line can be lumped together under the same heading, it’s usually the case that sociological interest by and large eclipses literary merit. Even so, getting a read on “how poets responded to the moon landing and its aftereffects on the imagination,” as Mary Ruefle puts it in “Poetry and the Moon,” is not without a certain appeal as its own sketchy field of inquiry. Consider the following short list a sampler rather than a survey.

Archibald MacLeish, “Voyage to the Moon” (New York Times, July 21, 1969)

Just two bylines appeared on the Gray Lady’s cover page under the banner headline MEN LAND ON THE MOON: chief science reporter John Noble Wilford and three-time Pultizer-winning poet Archibald MacLeish. His poem was commissioned on deadline by Times editor AM Rosenthal, who wrote a column about it for the twentieth anniversary:

We decided what the front page of The Times would need when the men landed was a poem.

What the poet wrote would count most, but we also wanted to say to our readers, look, this paper does not know how to express how it feels this day and perhaps you don’t either, so here is a fellow, a poet, who will try for all of us.

We called one poet who just did not think much of moons or us, and then decided to reach higher for somebody with more zest in his soul – for Archibald MacLeish, winner of three Pulitzer Prizes. He turned in his poem on time and entitled it “Voyage to the Moon.”

Bonus coverage: Harvard Law School, Poet on the Moon: Harvard Law School lawyer, poet, and statesman Archibald MacLeish LL.B. 1919 reads “Voyage to the Moon.”

W. H. Auden | “Moon Landing”

That dyspeptic poet Abe Rosenthal called first for the Times, the one who “did not think much of moons or us”? All the Gotham literary scuttlebutt agreed: WH Auden, a longtime NYC resident at 77 Saint Marks Place in the East Village. Turns out Auden was just biding his time. Nobody ranks “Moon Landing” as top-shelf Auden, but plenty appreciate its mordant wit and bite. “From start to finish, it’s one long grumble,” Nina Martyris writes in her 2019 piece “Auden’s Grumpy Moon Landing Poem,” and that’s what she likes about it. Noting an earlier Auden poem that addressed the moon as “Mother, Virgin, Muse,” Martyris takes his animus as the real thing: “Now it had a flag on it and had been exploited for television.” A minority report, it would seem. Here’s Thomas Mallon sizing up the poem in his lively 1989 moon-lit polemic “One Small Shelf for Literature”:

In 1930 W. H. Auden had happily noted that the “lunar beauty” he was observing had “no history”; four decades later it did, thanks to “a phallic triumph” at which he blew a bardic raspberry: “Worth going to see? I can well believe it. |Worth seeing? Mneh!”

James Dickey | “The Moon Ground”

Commissioned by ABC News and broadcast with a reading by Dickey on the network show Apollo 11: As it Happened. Dickey also wrote an earlier poem circa Apollo 7, “A Poet Witnesses a Bold Mission,” published in Life magazine on November 1, 1968. The poet witnessed it and was all for it, welcoming the astronauts to the club: “In a sense they are all poets, | expanders of consciousness beyond its known limits.”

Gil Scott-Heron | “Whitey on the Moon”

I can’t pay no doctor bills | But Whitey’s on the moon | Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still | While Whitey’s on the moon

Searing spoken-word performance by the “Godfather of Rap” on his 1970 debut album Small Talk at 125th Street and Lenox. Makes Auden’s kvetching sound like sweet nothings.

Simon Armitage | “Conquistadors”

the astronaut in him | doing his damnedest to coincide | the moon landing | with his first kiss

Current UK Poet Laureate’s first poem in the chair, written for the 50th anniversary of the moon in July 2019. Highlight: cameo appearance of a six-year-old “Simon Armstrong” as he “steps from the module | onto Tranquility Base.” Bonus coverage from Armitage’s interview with the UK Guardian, quoting English poet Robert (The White Goddess) Graves’s gut reaction to the first moonwalk: “the greatest crime against humanity in 2,000 years.”

Bonus Track ft. The Moonwalk

Michael Jackson | “Billie Jean” (25 March 1983)

Honorary category: the smash hit Michael Jackson was performing on the 1983 ABC special Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever when he busted his signature dance move, the “moonwalk.” The only thing new about it was the name. As exhaustively documented in print and video, the dance step executed by gliding backwards while appearing to walk forward – almost as if the dancer were floating in air – had long been a crowdpleasing tap-dancing bit known as the “backslide.” (“When Michael Jackson moonwalks,” the dance scholar Megan Pugh writes in American Dancing: From the Cake Walk to the Moon Walk, “he follows in the steps of both 1970s California street dancers and nineteenth-century blackface minstrels.”) But nobody had remade it in their own image until the taped special aired in May 1983, and nobody had known it as the moonwalk. It’s the perfect name for a pop star’s perfected move, even if it remains murky whether the true coiner was the moonwalking dervish himself. No matter – it’s a name-brand moniker if there ever was one, the only possible title for the peak-cult 1988 memoir. Jackson’s endless online tape-loop – maybe two seconds at most of “coasting backward across the stage, step by gliding step, as if on a cushion of air,” as dance critic Sarah Kaufman wrote in her 2009 obit – will always be the mother of all moonwalks.

List of Images & Sources

1. Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) 1936

Wood, glass, plastic, paper, box construction

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn.

Source: ArtNet

2. Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) c. 1957

The Art Institute of Chicago | The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation

3. Joseph Cornell, Soap Bubble Set (Lunar-Space Object) c. 1959

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

4. Joseph Cornell, Soap Bubble Set 1948

Box construction: cork, glass, velvet, gouache, clay pipes, coral, painted wood, and paper collage

Source: Sotheby’s Lot 29 (2019)

5. Joseph Cornell, Soap Bubble Set (Lunar Rainbow, Space Object) c. 1950s

Box construction Source: ARTFORUM

6. Joseph Cornell, Soap Bubble Set c. 1949-1950

Glasses, pipes, printed paper, and other media in a glass-fronted wood box

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Two notes on Joseph Cornell’s Soap Bubble Sets

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) 1936

Kirsten A. Hoving, “The Surreal Science of Soap: Joseph Cornell’s First Soap Bubble Set.” American Art (Spring 2006)

In 1936 Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) exhibited his first Soap Bubble Set at the Museum of Modern Art’s ground‐breaking exhibition entitled Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. A work that the artist later acknowledged as the first of an important line of shallow boxes with objects and collage elements, Soap Bubble Set is an important signpost in the artist’s early career. Variously interpreted by scholars as an autobiographical work describing Cornell and his family or as a vague rendition of the cosmos, it has puzzled scholars who have attempted to define the work’s meaning.

On one level, Cornell’s Soap Bubble Set belongs to the context of surrealism in America. It was produced for an important exhibition of dada and surrealist art, and Cornell chose “safe” items for it—such as a clay pipe, an egg, and a map of the moon—that would be familiar to anyone versed with surrealist imagery. However, in this work Cornell did not simply juxtapose familiar objects in strange ways to create the atmosphere of a surrealist dream. Instead, he used the vocabulary of surrealism to make a complex statement about the physical cosmos, paying homage to Galileo while also acknowledging exciting new theories of the expanding universe.

Soap Bubble Set c. 1949-1950

Joseph Cornell (1903-1972)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Soap Bubble Set offers a theatrical glimpse into the cosmos. Situated on Earth, the viewer observes the mountains and valleys of the moon, first discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. The glasses, holding specimens of land and sea, embody the gravitational pull of the earth, perhaps in relation to the lunar influence on tides. The freely moving sphere rolls between the opposing forces while cutouts of shells, stars, and other references to the natural world float above. Following Edwin Hubble's confirmation of the rapidly expanding universe in 1929, the metaphor of a swelling soap bubble proliferated in the popular press. For Cornell, who had a long-standing interest in astronomy and stayed abreast of breaking news, this metaphor would have resonated with his own memories of blowing bubbles with clay pipes as a child and the wonder of their creation. Cornell’s series of Soap Bubble Sets, sometimes called planetariums, is a decade-long rumination on the great astronomers of the past and the contemporary discoveries and innovations in space technology.