It’s a headline guaranteed to turn heads. Maybe you’ve heard of the WMF Watchlist and maybe you haven’t, but either way it’s the stuff of doubletakes:

World Monuments Fund Announces 2025 Watch

Including the Moon, Swahili Coast, Gaza, Ukraine

That’s not clickbait from The Onion or a chyron on SNL. It’s legit. It’s a bonafide dot.org banner. The World Monuments Fund (WMF) has just issued its biennial watchlist, per usual a slate of 25 threatened or vulnerable cultural heritage sites worldwide.

Worldwide until now. Memo to Earthlings – the Moon. The announcement was posted two days after the full “Wolf Moon” on January 15, and there’s no burying the lede. The Moon has made the Watchlist.

No kidding – the Moon. There are 24 other entries on the latest WMF roster of international sites at risk – including the Kyiv Teacher’s House in Ukraine, the Buddhist Grottoes of Maijishan and Yungang in China, the Waru Waru Agricultural Fields in Peru, and the Swahili Coast of Africa – but as far as optics go they all take a backseat to the Moon, the world’s one and only. It’s a new frontier for the global advocacy program that’s celebrating its sixtieth anniversary this year, the first time anything extra-terrestrial has appeared on the WMF’s running list of “historic places facing major challenges such as climate change, tourism, conflict, and natural disaster.”

If you thought that was all just a mess our own small planet has gotten itself into, think again. Move over, Earth, make room for the Moon. It’s been 55 years and counting since Apollo 11 touched down on the lunar surface, and there’s no time to lose. “As a new era of space exploration dawns,” the press bulletin begins, “international collaboration is required to protect the physical remnants of early Moon landings and preserve these enduring symbols of collective human achievement.”

By the Moon the WMF means the lunar surface, namely the coordinates of the first moonwalk in the Sea of Tranquility. You’ve seen the footage and the photos umpteen times, but it’s still a trip to be reminded how much paraphernalia is still up there:

The landing site, known as Tranquility Base, preserves some 106 assorted artifacts related to the event, including the landing module, scientific instruments, biological artifacts, and commemorative objects, as well as Neil Armstrong’s iconic boot print.

All relics worth preserving, but what’s the rush? It sounds like the moondust keeps things in mint condition.

Short answer: package tours. Junkets. Joyrides.

The naked truth can’t be concealed by the gauzy parlance – the new era of space exploration hasn’t just dawned, it’s homing in on high noon, all systems go. The overlords of pay-for-play space tourism have the Moon in their sights, and any day now they’ll be selling tickets. The race to the Moon is now a sweepstakes over who will be hawking the most kickass shuttle service.

The Watchlist isn’t naming names and it doesn’t have to. Flight plans to the Moon are all over the news. On the very same day the WWF posted its latest list, a SpaceX Falcon rocket blasted off with a payload of two privately built lunar landers for express delivery, a double-barrelled moonshot to conduct recon for future missions. One rocket, two start-up spacecraft ventures splitting the transport costs, a sign of the times. Space exploration is just another word for space entrepreneurship these days. Next stop: exclusive resort timeshares with scenic vistas over the Sea of Tranquility.

Lame punchline? Don’t be so sure. It was just last February that the Odysseus spacecraft designed by the Texas firm Intuitive Machines touched down near the lunar South Pole. It marked the first American moon landing since Apollo 17 in 1972, and the first-ever under private mission control.

It was a big deal, even if everything didn’t quite go according to plan. One leg of the lander broke off on impact, leaving the contraption tipped over against a slope. Hate it when that happens, but the NASA status reports showed that the on-board instruments remained in good working order and were relaying data with no glitches. Odysseus had landed and there it will stay. Intuitive Machines, in partnership with NASA, has two more contracted missions on the docket. Attention, Earthlings – now you see why the Moon is on the Watchlist.

All of which is to say, watch this space. Nearly a year after the Odysseus landing the honeymoon isn’t close to over. The future is now and it’s not just the technocrats who are pumped. All sorts of arts and culture curators want a piece of the action. On board the spacecraft was the latest installment of the Lunar Library created by the Arch Mission Foundation, a multi-pronged ongoing project that the non-profit describes as “an ultra-durable archive of humanity.”

You know, a time capsule.

For anyone of a certain age, it’s like revving up the wayback machine. We’ve been here before, only this time it’s less about the universe and more about us. When NASA launched its two interstellar Voyager missions in 1977, both probes were outfitted with identical Golden Records, twin gold-plated LPs containing an eclectic compilation of analog images and audio tracks. The two discs were encased in aluminum jackets complete with a stylus and cover diagram in binary code, stamped with the label The Sounds of Earth.

A time capsule, but not really. More like an exercise in testing the limits of the earthbound imagination. More like a message in a bottle. The astronomer Carl Sagan, chair of the committee NASA convened to select the tracks for the Golden Record, put it this way: “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

The Golden Record was meant to be the gold standard. Much ado was made about assembling a stellar set of grooves that would put life on Earth in the best light. These were pre-digital times, mind you, so it was only natural for Sagan’s star chamber to give prime attention to what should go on the soundtrack. The Sounds of Earth would be pressed on the record’s inner ring, but for all intents it could have gone by Earth’s Greatest Hits.

They’re still out there, the two Voyagers mounted with their Golden Records, travelling further into the interstellar cosmos than any other Space Age objects by a long shot. In his 2017 New Yorker article “How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made,” the sensei science writer Timothy Ferris marked the mission’s fortieth anniversary as a milestone of starry-eyed inspiration, musing on how it still goes to show that “there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe.” That collective “we” also happens to be wholly personal. Ferris was a close friend of Sagan back in the day, and his fingerprints were all over the making of the Golden Record.

It makes for some memoir. NASA gave Sagan the green light and a tight deadline. Ferris was all-in. They were mutual audiophiles and hatched plans for a playlist that would be nothing less than “an audio history of our planet.” They had to work fast and they would need to book studio time with all-pro mixmasters. They would cut a record. It would be gold.

The committee called it The Sounds of Earth. They could have called it Earth’s Greatest Hits. There were tracks laid down with natural sounds and the sounds of Homo sapiens. Sounds of fire, sounds of rainfall, footsteps and heartbeats, a kiss, a laugh. Greetings in many languages, wolf-howls, whale-songs.

The big draw of course would be the sound of music. It wouldn’t be a Golden Record without chants and songs and symphonies. Ferris took on the role of producer and hoped to enlist the services of his favorite ex-Beatle John Lennon. Lennon was game, but “tax considerations obliged him to leave the country.” Ferris’s consolation prize was signing up Lennon’s control-room whiz-kid and future industry mogul Jimmy Iovine as the project’s studio guru.

Nothing against the classic back catalogue of Mother Nature, but recorded music by the human primate was always going to be the heart and soul of the Golden Record. Ferris tells us he went so far as to say so for the record, taking a leaf from Lennon and inscribing a personal note right there on the pressed LP:

Lennon’s trick of etching little messages into the blank spaces between the takeout grooves at the ends of his records inspired me to do the same on Voyager. I wrote a dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.”

Boss starman Carl Sagan was of the same mind. In the 1978 book Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record, co-written with the rest of the team, Sagan took up the subject in a passage that has since become proverbial:

Perhaps there is a “universal” music. In addition, I was cheered by an earlier remark of the biologist Lewis Thomas, president of the Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York City. When asked what message he would send to other civilizations in space, Thomas replied with words to this effect: “I would send the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach.” But that, he added as an aside, “would be boasting.”

Bragging rights or not, so far the Golden Record appears to have fallen on deaf extraterrestrial ears. There’s no indication of any intelligent life tuning into the Glenn Gould version of “Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C Major” from Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier or rocking out to Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” Voyager 1 is still transmitting radio signals back to NASA mission control from more than 15 billion miles away in deep space, but the on-board audio might as well be filed in the remaindered bin.

The funny thing is, until a few years ago nobody here on Earth was listening to it either. Sagan and Ferris, et al., had anticipated that the finished product would see commercial release in due course, but it was not to be. As Ferris reports in “How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made,” it wasn’t until a Kickstarter campaign in 2016 that there was a will and a way to get the master tapes out into the world. Released by Ozma Records, the three-LP Voyager Golden Record: 40th Anniversary Edition went on to win a 2018 Grammy for “best boxed or limited-edition package.”

It’s a real blast from the past. Even just skimming the track listing, it’s a bit chastening to get a crash course on how such things went down in the age of analog. Only so many tracks, running times only so long, the audio quality from antique vinyl and acetate demos at best only so-so. Longest musical cut: the first movement (“Allegro con brio”) of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, the Otto Klemperer Philharmonic version clocking in at 8:49. Shortest:“Wedding Song,” by young girl from Huancavelica [Peru], recorded by John Cohen [founding member of the New Lost City Ramblers], at 0:42. The record was golden, but the recording specs were draconian.

No walk in the park to pull it off in those days, and that’s what makes it such a historical touchstone as a thought-experiment in action. What would you want The Sounds of Earth to sound like out there across the universe, when you only have so many sound-waves to work with? Every note and beat and treble clef has to count. Only an hour or so of music will survive the cut.

You’d think the committee meetings would have broken out into one big food-fight, but Ferris recalls almost no wrangling. Something about the categorically impossible ambition of it all seems to have made the whole thing hubris-proof from the start. The two gold-plated LPs would be duplicate time capsules, but not the brassy kind that pretends it can beat time at its own game. “They were a gift,” Ferris writes, “proffered without hope of return.” You could call the Golden Record a time capsule, but better to think of it as a timeless gesture. A humanistic gift up for grabs, airmailed with no strings attached to the space-time continuum.

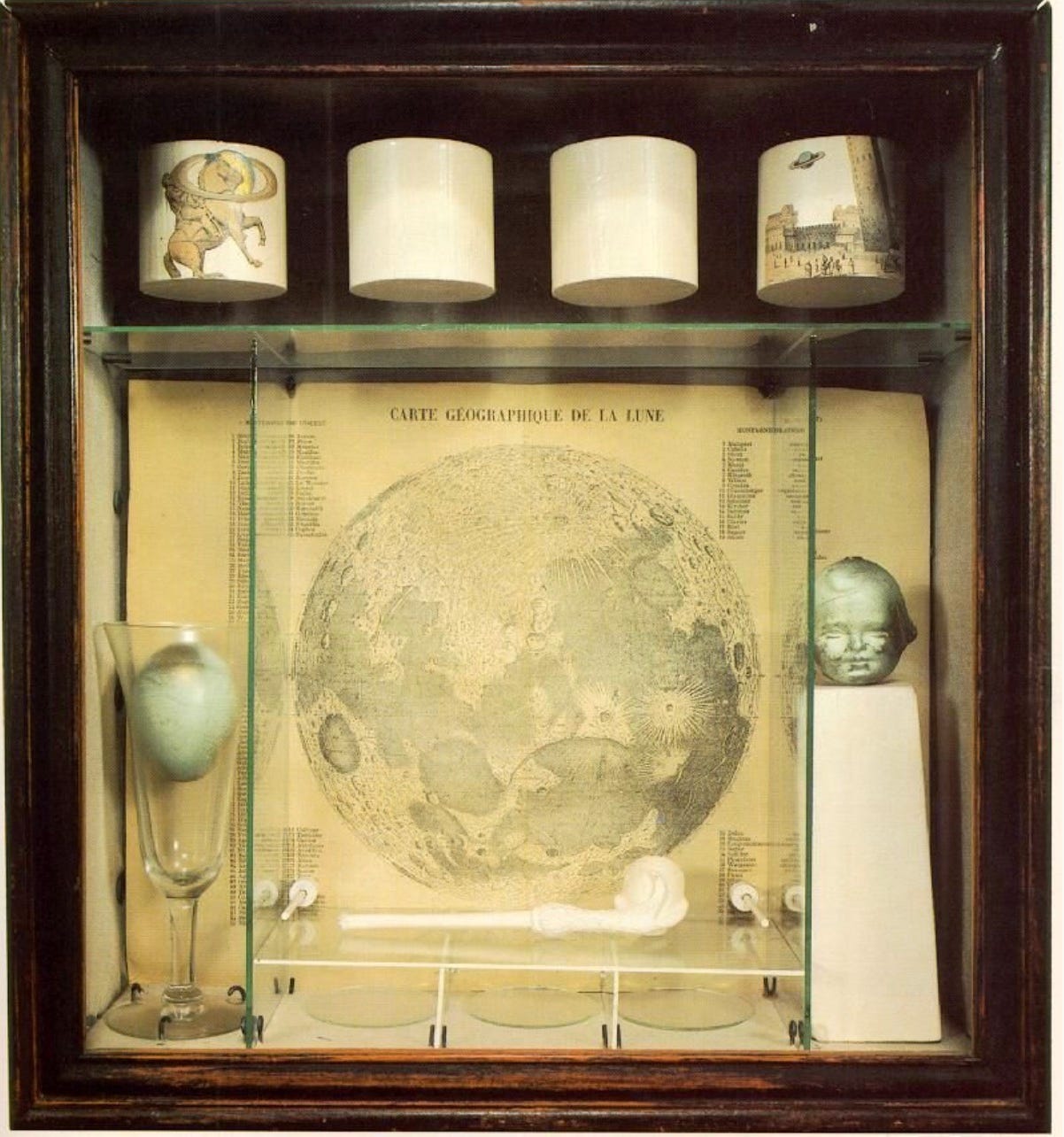

Fast-forward to our new era of space entrepreneurship and the vibes are worlds apart. The Moon is on the WMF Watchlist and now there’s something called the Lunar Library up there. It’s officially called the Galactic Legacy Archive. It’s the cornerstone of an ongoing project that “aims to create a long-lasting offworld archive of human knowledge.”

You know, a time capsule.

We’ve been here before, kind of. This time it’s got almost nothing to do with the universe and almost everything to do with us. It’s all about how many gigabytes of digitalized stuff can be packed on discs the size of DVDs. It’s all about the proprietary nickel-based Nanofiche data storage, projected by its patent-holder to be good to go for at least 50 million years on the lunar surface. It’s all about stashing things on the Moon for safekeeping.

All kinds of things, mostly all about us. Spoken and written language, thousands of world languages, “the linguistic heritage of all of humanity.” Thousands of crowd-sourced images, hundreds of copies of Neolithic cave paintings. Data sets written with synthetic DNA, literary classics from Project Gutenberg, the Torah, the Bible, the Koran, and in case you were wondering, “David Copperfield’s Magic secrets.”

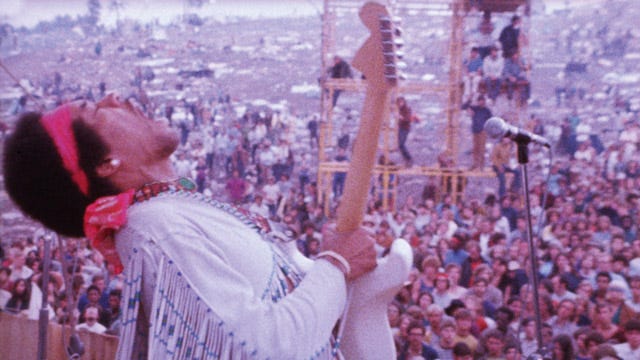

Also: music. Mostly pop music, so far. Classic rock, British Invasion, R&B, AOR. Elvis, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Marvin Gaye, Bob Marley, The Who. The premier industry trade journal was all over it: “Billboard can now reveal that the lunar lander made musical history as well, bringing digitized recordings from some of the most iconic musicians of all time to an arts-centric time capsule that’s currently sitting on the moon’s silent surface.”

A digital update of the Golden Record, kinda sorta. Another time capsule making musical history, but any meaningful resemblance ends there. Nothing under the purview of NASA this time, not the brainchild of a select committee of enthusiasts striving for the sonic gold standard. Another track-list of iconic music sent off into outer space, but nothing at all like a message in a bottle launched into the cosmic ocean. This time it’s all about hoarding earworm pop tunes on the Moon for the ages.

Billboard’s Joe Lynch fleshes out a few technical details and a lot of proper nouns. It’s complicated. The Lunar Library that hitched a ride to the Moon on the Odysseus mission is no one thing but a commercial consortium with various irons in the fire. The curator of the “musical moon museum” is one Dallas Santana, who runs a company called Space Blue. It was Santana who “came up with the idea of sending 222 artists to the moon and pitched it to the Arch Mission Foundation,” and then directed Space Blue to work with Galactic Legacy Labs to engineer the payload of digital files that was “affixed to the Intuitive Machines-built craft.”

It’s complicated. According to Santana it was also top-secret. NASA wasn’t in on it, and neither was SpaceX. The playlist was his baby, and no plutocrat rocketeers would have any say in it. “And musicians were concerned about that,” the Space Blue CEO told Billboard. “They said, ‘Does Elon Musk have anything to do with deciding what musicians go up there?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely not, this is a private payload.’ ”

A private payload, might as well call it a bespoke jukebox. Not an unconditional gift in the name of all humankind, more like a vanity project. The curator of the musical moon museum called the shots, and requisitioned a groovy soundtrack featuring “music from 1969 and artists who played Woodstock.”

You know, the year of the first moon landing and all. A symbolic tribute, but also a secret. Everyone kept in the dark, but not to fret. You can take Curator Santana’s word for it: “This is music that stands the test of time.”

Guess we’ll see about that. The tech bros say it’s good to go for 50 million years, give or take an epoch. Those far-out Woodstock jams will be safe up there on the lunar surface like, dude, forever. No vault or silo on earth stands a chance in hell of stacking up.

Not a snowball’s chance, and that’s exactly the point. We need someplace out of harm’s way to stash our stuff. As filmmaker and Lunar Library sponsoring partner Michael P. Nash tells Billboard, “In case we blow ourselves up with a nuclear weapon or a meteor hits us or climatic change wipes us out, there’s a testament of our history sitting on the moon.”

In that case, why curate? What’s the sense in losing sleep over what should make the cut? Surely nanotech is getting to the point where everything under the sun can be digitalized with countless microchips to spare. You’ve got to figure any day now the whole shooting match will be one big data-dump.

Just imagine what that could mean for the Lunar Library’s audio archive alone. You’d have the Golden Record to end all Golden Records, the Sounds of Earth as one astronomical boxed set, the Ultimate All-Time Signature Edition. The greatest hits, the deep cuts, the alternate takes, all the bootlegs. Millions of tracks good to go for millions of years, a complete and unabridged earthling playlist. Hit play, shuffle all.

On second thought, bad idea. It would spoil all the fun. The Galactic Legacy admins like to bill themselves as cultural curators, with Arch Mission co-founder Nova Spivack going all meta in stating that the foundation’s philosophy is to “curate the curators.” Whatever they call what they’re curating – time capsule, lunar library, off-world archive, arts-centric payload – they want it to be known they’re curators by calling.

You really can’t blame them. It’s cool to be a curator. Everyone wants to be a curator. Curators rock. We’ve all got a little curator in us now.

The Golden Record is still out there somewhere, but time capsules aren’t what they used to be. The Moon is on the Watchlist, but the Anthropocene has flipped the script. The lunar surface is the new frontier for digital stockpiling, and the next big thing in cultural curation. You know, just in case a meteor hits or we wipe ourselves off the face of the earth.

In the meantime, let’s not spoil all the fun. It’s cool to be a curator, even when it’s just a parlor game. We’ve all got a little curator in us now, so imagine the dream mixtape you’d charter on the next lunar payload if it were your call. It had better be good and it has to stand the test of time. It will be sitting pretty up there for eons.

Here’s my bright idea. A curated lunar roster of songs and poems all about the Moon. It’s a heady curatorial exercise if there ever was one. Lines and lyrics about the Moon or to the Moon, our one and only. There’s a multitude out there, going back to when the world was young. The Moon in all its phases and guises, lauded by poets and troubadours the world over. It’s a moonstruck earthly legacy unto itself.

So here goes. My own curated playlist of poems and songs for a fantasy lunar payload, just for fun. A one-off annotated short list just to get things off the ground. A vanity project, like all the off-world archives already up there. Hardly comprehensive, roughly chronological. A loony thing to do, but don’t spoil my fun. The Moon is on the Watchlist, and there’s no time to lose.

Shoot the Moon: A Lunar Payload Playlist