1.

— So then what do you love, you extraordinary stranger?

— I love the clouds ... the passing clouds – up there, way up there … the marvelous clouds!

“The Stranger” (L’Étranger), the first of fifty strange “little poems in prose” found in Charles Baudelaire’s strange posthumous opus Paris Spleen, published in 1869, two years after his death. Printed with a prefatory Dedication: For Arsène Houssaye. A strange little epistle to the editor of La Presse, part preening crypto-manifesto, part posturing sales pitch:

Dear friend, I send you a work no one can claim not to make head or tail of, since, on the contrary, there is at once both tail and head, alternating and reciprocal…. Cut out any vertebra and the two pieces of this serpentine fantasy will easily rejoin. Chop it into many fragments and you will see how each is able to exist apart. Hoping some of these stumps will be lively enough to please and amuse you, I make bold to dedicate to you the entire snake.

A strange new kind of poetry – no stanzas, no syllabic measures, no rhymes, all that jettisoned in pursuit of an exalted form of prose repurposed for “the description of modern life.” The dedication doesn’t mince words:

Who among us has not dreamt, in moments of ambition, of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm and rhyme, supple and staccato enough to adapt to the lyrical stirrings of the soul, the undulations of dreams, and sudden leaps of consciousness. This obsessive idea is above all a child of giant cities, of the intersecting of their myriad relations.

Passing strange, stranger and stranger. Strangely audacious, strangely auspicious, peculiarly Parisian. The miracle of a poetic prose! Stirrings, undulations, sudden leaps! Giant cities! Who among us has not dreamt, indeed? Reads like a ghostly reverie, strangely imperishable. A ghostly reverie, a trippy last will and testament, a strangely ensorcelling assortment of little poems in prose, starting off with that strange little poem in prose, “The Stranger.”

THE STRANGER (L’Étranger)

— Tell me, who is it you love most, enigmatic man? Your father, your mother, your sister,

or your brother?

— I have no father or mother, no sister or brother.

— Your friends?

— Now you use a word I’ve never known the meaning of.

— Your country?

— I don’t even know the latitude where it lies.

— Beauty?

— I would love her willingly, a goddess and immortal.

— Gold?

— I hate it like you hate God.

— So then what do you love, you extraordinary stranger?

— I love the clouds ... the passing clouds – up there, way up there … the marvelous clouds!

Charles Baudelaire, Le Spleen de Paris (1855-1867). Translation mine.

2.

Clouds, the marvelous clouds. Baudelaire’s word of course is les nuages.

Oil and water, chalk and cheese. Cloud, from the Old English clud as in clod, “lump of earth or clay” or alternatively “mass of rock, hill,” the modern sense of “rain-cloud” believed to be a later variant in Middle English arising from the perceived resemblance of hilly mounds and cumulous clouds.

Nuage something else again, not even close. From the French nue, cognate with the Latin nūbēs, a fan-deck word with multiple shades of meaning for all things cloudy – cloud, mist, haze, dust, smoke, vapor; obscurity, concealment, a veil, a phantom; dense mass, swarm, gloom, threat (of war), and so on. Nue now archaic, and even in its prime “chiefly poetic,” more to do with metaphor than meteorology from the get-go. Nuage the French noun arrived at by hitching nue to the suffix –age, meaning “as a result” of the thing, the word for cloud resulting from a figurative expression mutating into the thing itself.

It’s the one thing the extraordinary stranger loves. The clouds, the passing clouds. But what is it about the clouds the stranger loves? He’s not saying. There’s no knowing. It’s hazy. Something to do with the grand passing spectacle. Something about the utter unbridled marvel.

The clouds, the clouds. J’aime les nuages… les nuages qui passent… là-bas… là-bas… les merveilleux nuages! It’s the là-bas… là-bas that steams up the windowpane. The English poeticism “on high” won’t wash. The phrasing is stranger than that. As Kent Dixon quips in a 2015 essay for the translation journal Transference, the idiomatic sense of là-bas might best be approximated in English as “Over-there” only more far-out, “a kind of you-can’t-get-there-from-here Over-there.”

Là-bas… là-bas. The double-take seals it – what the stranger loves, really loves, is the strangeness of the clouds, strange beyond all reason and reckoning. The clouds in all their strangeness, and les nuages all the stranger.

All the stranger because that much closer to the Proto-Indo-European root nebh and its tangled web of associations – the Sanskrit nabhas (vapor, cloud, mists, fog, sky), the Old English nifol (dark, gloomy), the Latin nebula (mist, fog, smoke, exhalation).

Nebula, from which we get the English word for “an interstellar cloud of gas or dust” and the adjective nebulous, attested to by 1831 in its now-familiar figurative sense of describing things said to be vague or formless, as in German Romantic landscape painter Caspar David (Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog, c. 1817) Friedrich’s professional observation, “The eye and fantasy feel more attracted by nebulous distance than by that which is close and distinct in front of us.”

It gets stranger. There’s nebulous and then there’s nuance, nuance originally meaning “shade of color” in the French, later absorbed into English as “A subtle or slight variation or difference in meaning, expression, feeling, etc.” First attested to in a 1781 letter by Horace Walpole: “The more expert one were at nuances, the more poetic one should be.”

Strange but true – the word nuance in French derived from the noun nue (cloud), derived in turn from the Latin nubes, same as nuages. Nebulous distance, expert nuance, same cloud family, all the more poetic, the varying tints of sunlit clouds giving rise to fine shades of meaning and feeling.

The clouds, the clouds. The clouds in all their strangeness, and les nuages all the stranger.

The nebulous nuances, là-bas… là-bas… les merveilleux nuages!

Strange stuff, more attractive to the mind’s eye than the things close and distinct in front of us. The more expert, the more poetic. Strange but true.

It’s the one thing the extraordinary stranger loves, really loves.

The clouds, the clouds, the clouds that never lose their strangeness.

3.

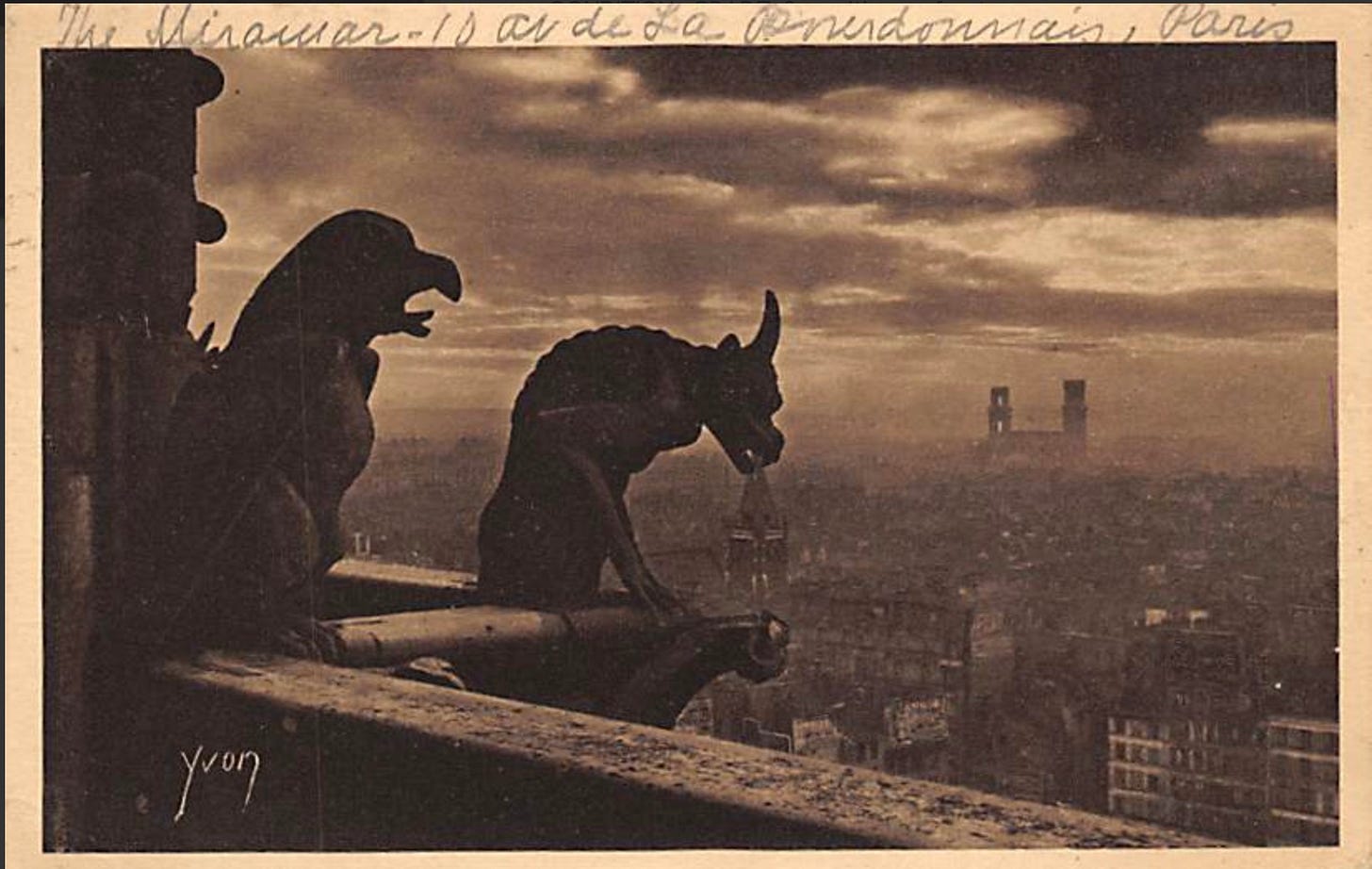

Strange stuff, getting stranger all the time. Stranger and stranger, as in curiouser and curiouser, just like Alice said across the Channel a couple years back in 1865. The stranger who loves the clouds has company. Further on in the same volume, another little poem in prose. A title like something out of a cabaret act: La Soupe et les Nuages, “The Soup and the Clouds.” Pithy, wacky, cockeyed, a portrait of the artist in cloud cuckoo land:

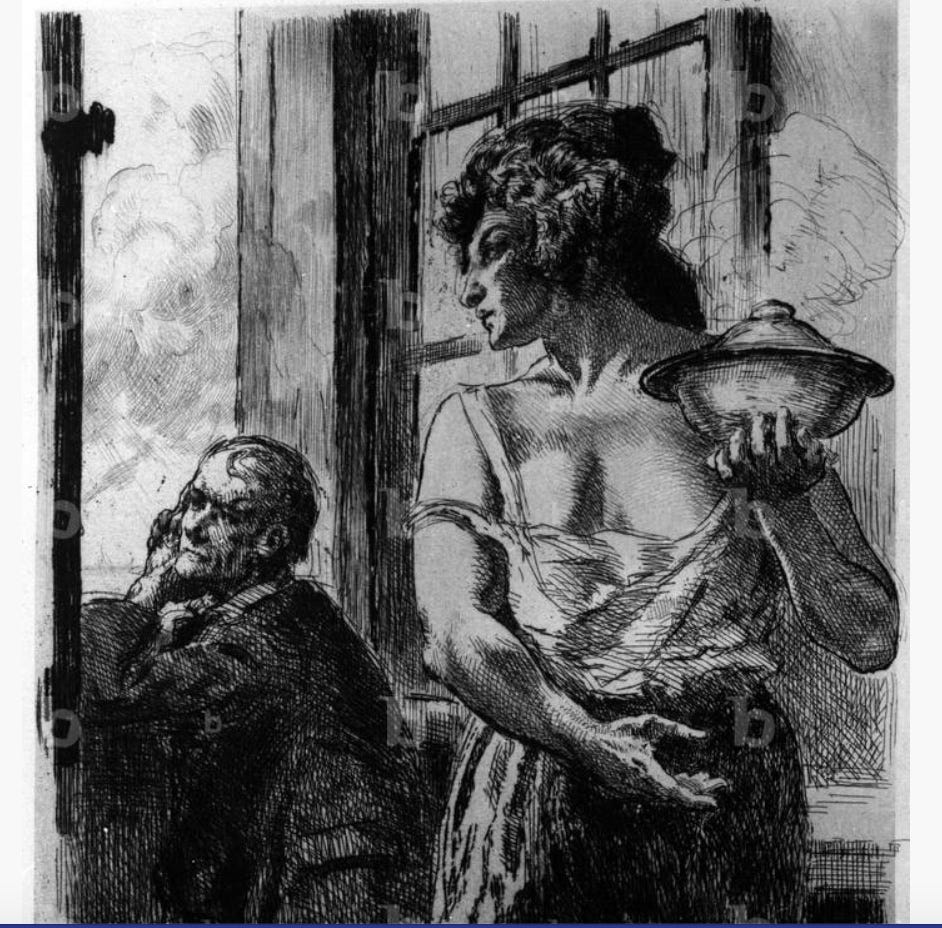

My dear little mad beloved was serving my dinner, and I was looking out of the open dining room window contemplating those moving architectural marvels that God constructs out of mist, edifices of the impalpable. And as I looked I was saying to myself: “All those phantasmagoria are almost as beautiful as my beloved’s beautiful eyes, as the green eyes of my mad monstrous little beloved.”

All of a sudden I felt a terrible blow of a fist on my back and heard a husky and charming voice, an hysterical voice, a hoarse brandy voice, the voice of my dear little beloved, saying: “Aren’t you ever going to eat your soup, you damned bastard of a cloud-monger?”

Paris Spleen, translation by Louise Varèse

Stranger and stranger, curiouser and curiouser. Too strange to be a true story, too strange to be a mere travesty. The extraordinary stranger’s got company – another lover of clouds, another strange cloud-smitten type.

Only this time it’s a love triangle, a showdown between his beloved and his beloved clouds. His dear little mad beloved and his dearly beloved phantasmagoria. That’s him at the open dining-room window now, caught in the middle. Torn between his beloved’s beautiful green eyes and those moving edifices of the impalpable. The soup on the table and the clouds in the sky.

The stranger’s got company – or are they two sides of the same racked soul? No telling, and no matter. It’s the clouds that count. The clouds are the common ground. Don’t forget, this is the poet who’s been dreaming, in moments of ambition, of the miracle of a poetic prose, finely calibrated to channel lyrical stirrings of the soul and sudden leaps of consciousness. No wonder his head’s in the clouds.

Stranger and stranger, curiouser and curiouser. The soup on the table and the clouds in the sky. The passing clouds, those marvels God constructs out of mist, up there, way up there. It’s nebulous and it’s nuanced. One man’s cloud cuckoo land is another man’s little piece of heaven. It’s a thin line between an extraordinary stranger who loves the clouds and a damned bastard of a cloud-monger.

4.

Spleen, Paris Spleen. Le Spleen de Paris, fifty strange “little poems in prose” kicking off with L’Étranger, “The Stranger.” Strangely audacious, strangely auspicious, peculiarly Parisian. Take it from the jacket copy of Keith Waldrop’s 2020 translation:

Between 1855 and his death in 1867, Charles Baudelaire inaugurated a new – and in his own words “dangerous” – hybrid form in a series of prose poems known as Paris Spleen. Important and provocative, these fifty poems take the reader on a tour of 1850s Paris, through gleaming cafes and filthy side streets, revealing a metropolis on the eve of great change. In its deliberate fragmentation and merging of the lyrical with the sardonic, Le Spleen de Paris may be regarded as one of the earliest and most successful examples of a specifically urban writing, the textual equivalent of the city scenes of the Impressionists.

Spleen. A strange word with a long strange history. An anatomical term first and last: “non-glandular organ of the abdomen of a human or animal,” now known to “produce certain changes in the blood,” splen in Middle English circa 1300, from the Greek splēn, “the milt.” The internal organ long held to be the source of “black bile” and hence the seat of the unruliest passions, doing double-duty in the typology of the humours as the fount of pervasive melancholy. Same meaning in French and English, attested early and often in the sense of bottomless dejection and gloom, seething rancor or corrosive spite, as when Shakespeare’s Richard III brays O preposterous | And frantike outrage, ende thy damned spleene.

Spleen. Le Spleen de Paris. No word so strangely but truly Baudelaireian. Four poems under that title in Les Fleurs de Mal (1857), the premier poète maudit blowing the dust off the term’s pseudoscientific associations and assigning it the status of a full-blown modern pathology. Spleen no longer merely a synonym for run-of-the-mill melancholy, a strain of melancholy taken to be the default setting for an inborn temperamental malady. Baudelaireian spleen something deeper and darker, melancholy as a terminal condition. Le Spleen de Paris, a posthumous assemblage of little poems in prose, an elliptical chronicle of malignant Parisian soulsickness. Spleen, as if scrawled in the blackest ink.

Is the extraordinary Stranger who loves the clouds suffering from a bad case of spleen? And our poor clobbered cloud-monger too? Could the clouds be the cure, or at least an anodyne?

Could be, but it’s not that simple. It’s nebulous and it’s nuanced. It’s nebulous, but Walter Benjamin had a nuanced hunch about it. In Benjamin’s fragmentary work “Central Park,” a series of notes for his unfinished book on Baudelaire dating from 1939, you’ll find several aphoristic remarks on Baudelaire’s signature affliction (“Spleen is the feeling that corresponds to catastrophe in permanence”) and one enticing passage on Baudelaire’s thing for clouds:

If, as generally agreed, the human longing for a purer, more innocent, more spiritual existence than the one given to us necessarily seeks some pledge of that existence in nature, this is usually found in some entity from the plant or animal kingdom. Not so in Baudelaire. His dream of such an existence disdains community with any terrestrial nature and holds only to clouds. This is explicit in the first prose poem in Le Spleen de Paris. Many of his poems contain cloud motifs. What is most appalling is the defilement of the clouds (“La Beatrice”).

No reference to the Stranger by name here, so it goes without saying that Benjamin’s Baudelaire speaks for himself. Hence the hunch. Nature offers no refuge from the tender mercies of Baudelaireian spleen. Nothing on earth answers to the Baudelaireian longing for spiritual communion. Only the clouds, the marvelous clouds, the clouds overhead.

How nebulous, how nuanced, how strange. How strange that clouds of all things would be untainted by Baudelaireian spleen. How do the clouds come by their special powers? Impossible to say, but the cloud motifs in many poems suggest it must be so. “I saw a cloud descending on my head | in the full noon,” runs the version of “La Beatrice” in Robert Lowell’s Imitations, “a cloud inhabited | by black devils, sharp, humped, inquisitive | as dwarfs.” If you’re not quite convinced that the scene lives up to Benjamin’s billing as an appalling defilement, you can’t deny it’s pretty damn besmirching.

Spleen, as if scrawled in the blackest ink. Paris Spleen, Baudelairean spleen, pathological melancholy, prognosis negative. Le Spleen de Paris, fifty strange little poems in prose written under the sign of spleen, starting right off the top with “The Stranger,” that strange little study in self-estrangement, reading like a redacted transcript of enhanced self-interrogation. Spleen also stewing away further on in “The Soup and the Clouds,” another astringent little spoonful of splenetic rue to make the bitter pill go down. Spleen like something in the water, spleen never failing “to plant his black flag on my drooping brows,” the poet croaks in Les Fleurs de Mal, spleen the thing infecting everything. Only the clouds are exempt.

Only the clouds, who knows why. They’re the one thing the poet who’s a stranger to himself loves, really loves. His mad monstrous little beloved is out of her league. His heart belongs to the clouds.

The clouds, the passing clouds, the clouds passing high above the cobbles and spires of Paris. The clouds, the clouds in all their nebulous nuances, là-bas… là-bas… les merveilleux nuages! The clouds, the clouds in all their strangeness, up there, way up there where spleen will never reach.