Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish…

Mark Antony has lost it. You can tell by the way he speaks to his old friend Eros. You can tell by the way he starts talking about clouds.

It’s Scene XIV in the rapid-fire Act IV. Cleopatra’s Palace. Another room. All is lost, the end is near.

He’s lost it, all of it. His squadrons have been routed at sea. His bosom buddy Enobarbus has sold him out. His war-ships have deserted him to take up with Caesar. Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, for whom he waged war on his native Rome, has plainly betrayed him. He’s lost it, lost it all.

All is lost, the end is near, and Mark Antony is there and not there, a shadow of himself. You can tell by the way he speaks when his old friend enters the room: Eros, thou yet behold’st me? He says it like he’s already a ghost.

He knows it’s over and he knows he’s lost it. He says so in so many words. You can tell he knows by the way he speaks. You can tell he knows by the way he starts talking about clouds.

He’s lost it, lost it all. He talks about clouds like he’s already a ghost. He’s speaking to Eros, but it’s not a conversation. He speaks in the first-person plural, but it’s not the royal we. He’s talking about clouds being phantom forms. He’s talking about clouds like he’s speaking in tongues. He’s talking about the way clouds hand us our heads. He’s talking about himself.

It’s a stark turning point in a late Shakespearean tragedy, a fallen hero’s stricken reckoning as the end nears. It’s a searing speaking part cutting to the quick of a star-crossed persona’s riven psyche, crushed under fortune’s wheel. It’s the sound of spoken English raised to the purest and surest pitch of lucid raving, the vocal cadence of visceral pathos, blank verse keeping a steady beat for a flaying soliloquy in full cry. It’s a tragic aria on losing it all, a virtuosic lyric poem unto itself:

ANTONY

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish;

A vapour sometime like a bear or lion,

A tower’d citadel, a pendent rock,

A forked mountain, or blue promontory

With trees upon’t, that nod unto the world,

And mock our eyes with air: thou hast seen

these signs;

They are black vesper’s pageants.EROS

Ay, my lord.

ANTONY

That which is now a horse, even with a thought

The rack dislimns, and makes it indistinct,

As water is in water.EROS

It does, my lord.

Antony isn’t done speaking, but that’s it for the clouds. They hover there in their spooky illusory glory, signs of a mind gone round the bend, a self in the throes of self-implosion. He’s seeing things – beastly shades and specters, vaporous lands and towns, a shadow-world, there and gone, there and gone. He’s seeing things – things he believed were other things, things as they really are, the scales falling from his eyes, such stuff as meltdowns are made on.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. In his magisterial study Shakespeare’s Language (2000), British literary critic Frank Kermode singles out this precise moment as an atom-splitting passage of dramatic poetry: “The intellectual energy of the verse is now probably more intense than anywhere else in Shakespeare, except possibly in Coriolanus, yet it is never completely wild.” For Kermode the utterance hits a flashpoint with the phrase “The rack dislimns”:

“Rack” is drifting cloud; “dislimns” is an essential, irreplaceably apt new word (later uses are quotations of this one, as the OED notes; an artist “limns” and the cloud breaking up does the opposite for the horse. Antony is dislimned like the shapes in the cloud; he “cannot hold this visible shape.”

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. Kermode’s otherwise trusty gloss undersells the metaphor’s force-field by somehow overlooking the wicked punning (“limbs” dismembered on the “rack,” anyone?), but that only amplifies the voltage of the verse here. There are no real clouds in the scene, only a sublime word-cloud. Mark Antony is seeing things.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and this time Mark Antony sees himself as just so much cloud-stuff. Sometimes things can only be spoken of in figures of speech, so just to make sure Eros and the groundlings get it, he explains in his next breath what his metaphor means: “My good knave Eros, now thy captain is | Even such a body: here I am Antony: | Yet cannot hold this visible shape, my knave.” He really shouldn’t go to the trouble. His word-cloud needs no parsing. No sooner does the horse rear up, up there, than it’s long gone. No sooner does he say his own name, right here, than he’s nowhere to be found. Now that all is lost, he’s lost all sense of who he is or ever was.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. The genius is in the -ish. Not a cloud that looks like a dragon – that would be much too obvious and much too obtuse. Not a dragon-shaped cloud – that would be way too cognitively sound and not nearly so unnerving. The -ish gives the cloud its fishy unfinished freakishness.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and the -ish is what makes it nightmarish, the very -ishness of it mocking our eyes with air. It’s been a puckish little part of speech practically from the start. In a nutshell, a promiscuous adjectival suffix from the Old English -isc, “of the nativity or country of” or more generally “of the nature or character of,” the usage already ushering in the shadow of a doubt. Here it’s -ish as in roughly, approximately, kinda, sorta, “inclined or liable to,” “having a touch or trace of,” but in any case not clear-cut – could be that trace of resemblance might just vanish, could be that touch of likeness is turning into something else even with a thought. It’s the -ish that makes Antony’s dragonish cloud so fiendish.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. The genius is in the -ish, and there’s always been something about sizing up clouds that fills our heads with -ishness. It could hardly be otherwise, seeing as probably no observable natural phenomena has proved as devilish to pin down in words. What can hold a candle to the clouds when it comes to mocking the naked eye? There and gone, there and gone, touch and go, now ursine, now leonine, now apparitions of mountains, or are they castles in the air? There and gone, touch and go, and that’s where all the -ishness rushes in.

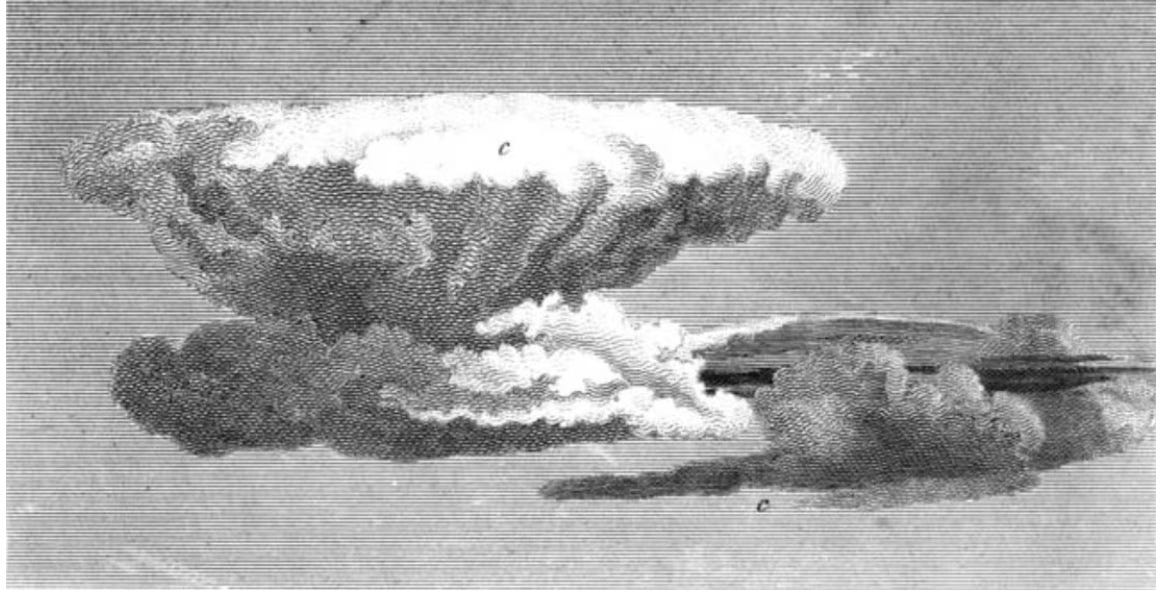

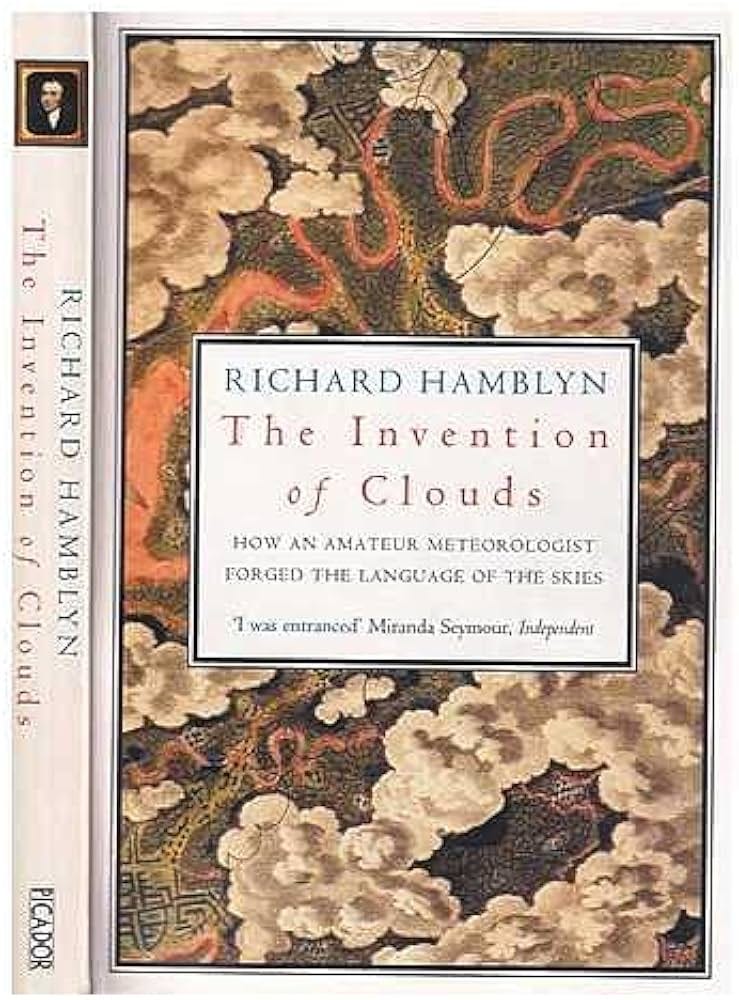

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and in the absence of any sort of common nomenclature, what you see is what you get. For all the fascination clouds have held for poets and philosophers since antiquity, for the longest time they raced beyond the reach of all rhyme or reason. As English author Richard Hamblyn tells it in the chapter “A Brief History of Clouds” from his 2001 book The Invention of Clouds: How an Amateur Meteorologist Forged the Language of the Skies, making sense of the spectacle of the cloudscape before the advent of modern scientific instruments never really got off the ground, an epic reign of error marked by one wild surmise after another from Aristotle’s Meteorologica on down. Clouds were their own dark continent, and no theory or hearsay could be counted out. There and gone, touch and go. Here be dragons.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. That’s poetry for you, and it was a bear for natural philosophy to keep up. Even as the first state-of-the art thermometers and barometers inaugurated “the era of the weather collector,” writes Hamblyn, “bafflement over clouds and cloud formation proliferated.” Going by a choice aperçu he plucks from Oliver Goldsmith’s 1774 tome A History of the Earth, and Animated Nature, the new science may have been in high gear, but clouds were still up to their old tricks:

Every cloud that moves, and every shower that falls, serves to mortify the philosopher’s pride, and to show him hidden qualities in air and water, that he finds difficult to explain.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and until the clouds were classified that was about as close as you could come to the gist of it. Dragonish, impish, nebulous, nameless – what you see is what you get. They could be anything. Their mutability and anonymity were of a piece. The stars had names. The winds had names. Not the clouds, not for the longest time. Not until Hamblyn’s “unknown young amateur meteorologist” Luke Howard gave a talk at a London laboratory in Plough Court upon an evening in December 1802. He’d been studying clouds for a good while now. He had the nomenclature all worked out. He had named the clouds, and now he proposed to lay to rest any notion that the study of clouds was “a useless pursuit of shadows."

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. So says Mark Antony, and who can quarrel with him? He’s seeing things. He sees what he sees, and so do we all. Dragonish, monstrous, insurmountably nebulous, sometimes delirious, sometimes numinous, despite no longer being nameless. Thou hast seen these signs.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and it’s there to remind us that classifying isn’t synonymous with demystifying. Meteorological geek-speak hasn’t made clouds any less potently metaphorical. Sometimes it can sound that way, but there’s usually a kinetic current of poetry in the air. Take the user-friendly companion handbooks The Cloudspotter’s Guide (2007) and The Cloud Collector’s Handbook (2011) produced by the UK Cloud Appreciation Society founder Gavin Pretor-Pinney. The basic idea here is to herd clouds under the big tent of the traditional pictorial nature guide, with cloud-spotting and cloud-collecting taken literally as the listing of names and the ticking of boxes. While that rules out all the random clouds only known to bamboozle us, in this case it still leaves ample space for the ones that work on us in mysterious ways.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, but that falls outside the purview of the Cloud Appreciation Society. Pretor-Pinney sticks to the nuts and bolts for the most part, keeping things plain and simple for the novice: “The system of naming clouds is rather like that of plants and animals, and uses Latin terms to divide them into different genera, species, and varieties.” But plain and simple in his book doesn’t mean dry as dust. As befits a big breeze in a cloud society, Pretor-Pinney isn’t merely an authority but an aficionado. He’s a veritable curator of cloud lore and an avid collector of cloud-centric literary allusions, now referencing Aristophanes’s cloud chorus as “patron goddesses of idle fellows” and now invoking everyday cloud systems “magicked into being by the inscrutable laws of the atmosphere.” Here he is in typical good form in The Cloud Collector’s Handbook, wrapping up his snappy opening pep talk on “How To Collect Clouds”:

While it may not have the permanence of a collection of coins, not the swapability of one of rare stamps, there’s something honest about a collection of clouds. Clouds embody the impermanence of the world around us. “Nature,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “is a mutable cloud which is always and never the same.”

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, honest-to-goodness, and if we take up cloudspotting sometimes we’ll see something called a sundog. Nothing akin to Antony’s horse or bear or lion, not a canine-like cloud, not a cloud at all. Turn to page 124 in your Cloud Collector’s Handbook: sundogs, “large spots of light that can appear on one or both sides of the sun…. formed as sunlight is refracted through the ice crystals of thin layers of clouds.” A light-show brought to you by certain types of cloudbanks, if you know when and where to look. Sometimes called “mock suns,” as Antony would approve, clouds mocking our eyes with airborne ice. Not a cloud, but a colloquialism for what some clouds can do, one of the many ways clouds are so good at making us see things.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. Mark Antony is seeing things, and it’s a sign that he’s lost it, lost it all. His soul-rending word-cloud hovers there, glorious and delirious, and it’s poetry, tragic poetry, poetry as a force of nature. He’s lost it, but he’s here to remind us that clouds will never lose the dragonish essence of their incessant —ishness. Call them by their proper names all you like, they still speak in their own sign language. Meteorology, metaphor, call it a draw.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and that’s how we know clouds can still take the form of our own mulish wishfulness and willfulness. Sometimes a cloud is just a cloud, but that doesn’t stop us from seeing things. You don’t need to be a cloud collector to see the signs. Not for nothing does the study of clouds as a branch of meteorology go by the name nephology, after the Greek cloud-nymph Nephele. Meteorology, mythology, same difference – clouds will always be unfinished business, always and never the same.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish. Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, there and gone, touch and go. Refraction, convection, condensation. Myth, metaphor, magic.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and we go look it up in a cloud guide.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and it means we’re seeing things.

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish, and that’s all there is to say.

Very like a whale: Field Guides to the Clouds

First installment in a running series on cloud atlases, cloud art, and cloud poetry