Pen and ink, forever the deft draughtsman, a sixth sense for punctilious nonsense, nonsense on the nose. Guittara Pensilis, first album, drawn on the spot before withering – a quartet of little guitars dangling by their necks from one tall stem, hanging there in one overlapping row a little like bluebells, a little like the real thing in a luthier’s shopwindow. Do they sound like they smell? Do they catch your eye by ear? Do they grow in all keys? Do you pick them like arpeggios? Synaesthesia, “sensation in one part of the body produced by stimulus in another,” Modern Latin from Greek syn- (“together”) + aisthēsis (“feeling”), dating in English from 1881. Now you can see why the French Surrealists caught wind of a fellow traveller in pursuit of the systematic derangement of the senses. Now you can see why American high chieftain of avant-garde taste Alfred Barr rustled up some of the nonsense works on paper for his 1936 MOMA exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, sandwiched in with the likes of Bosch, Blake, Picasso, Dali, Magritte, and Duchamp. Now you can see why bulldog bullshit-detector George Orwell was a fan, commending the spirit that makes its presence felt on the page as “a sort of poltergeist interference with common sense.” Isn’t that the heady scent of air guitar? Isn’t that the ghostly strumming of perennials in bloom? Didn’t you hear they can be crossbred with strains of banjo and mandolin? Can’t you tell it’s the growing season for tasty licks and nonsense refrains?

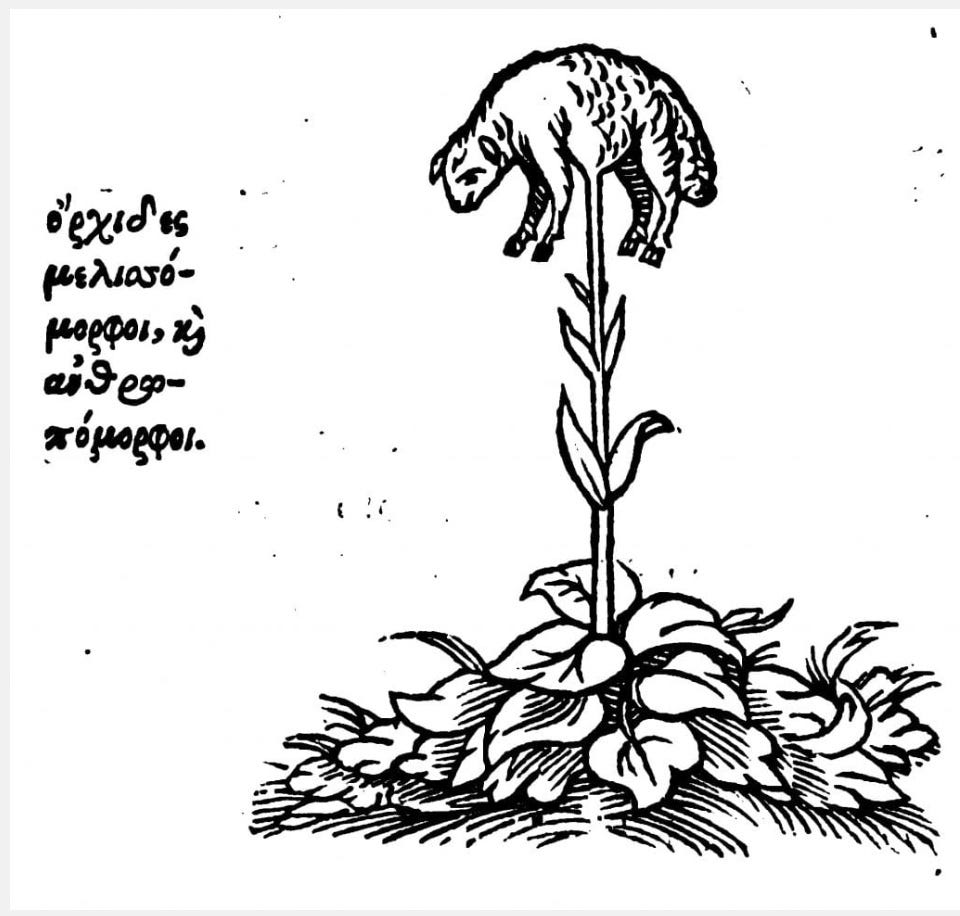

Stuff and nonsense – botantical specimens sprouting birds, pipes, bottles, forks, beaks, all scrupulously classified to the letter. Perfectly sensible, then, to scare up some truly beastly species. Piggiwiggia Pyramidalis – a fan-shaped bract of heliotropic swine budding out by the hindlegs, picked someplace where they grow hog-wild. Barkia Howlaloudia – a spiking stalk of baying dog-heads spiraling upwards in a snarl of snapping jaws. Tigerlillia Terriblis – a rare subspecies of the one you’ve heard of, five maneaters cheek by jowl in one big-ass unfurling blossom with long striped tails scrolling up their spines. Stuff and nonsense, but no more or less so than that fabulous zoomorphic marvel Agnus scythicus, the Tartary lamb, described in Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie as plant-bearing fruits that “look exactly like that animal … the same legs, hooves, ears, and head.” A tall tale, they say, but you’ve got to see the woodcut from Athanasius Kircher’s 1654 treatise Magnes sive de arte magnetica – a single young sheep in bloom high atop a leafy umbilical stalk with useless hooves dangling, a woolly zoophyte full of juice, not blood. Zoophyte, from the Greek, “animal-plant,” now fallen out of scientific usage but for a long stretch in wide circulation as a taxonomic class with the blessings of Linnaeus, his catch-all term for “composite small organisms, with both animal and plant characteristics” like corals, sea squirts, comb jellies, and sponges, a fudging label so handily expedient as to still crop up in Darwin’s early writings even as the science sped it into obsolescence, hard to shake even as it was shown in no uncertain terms to make no sense. Stuff and nonsense, next stop Tartary and the Jumbly Islands.

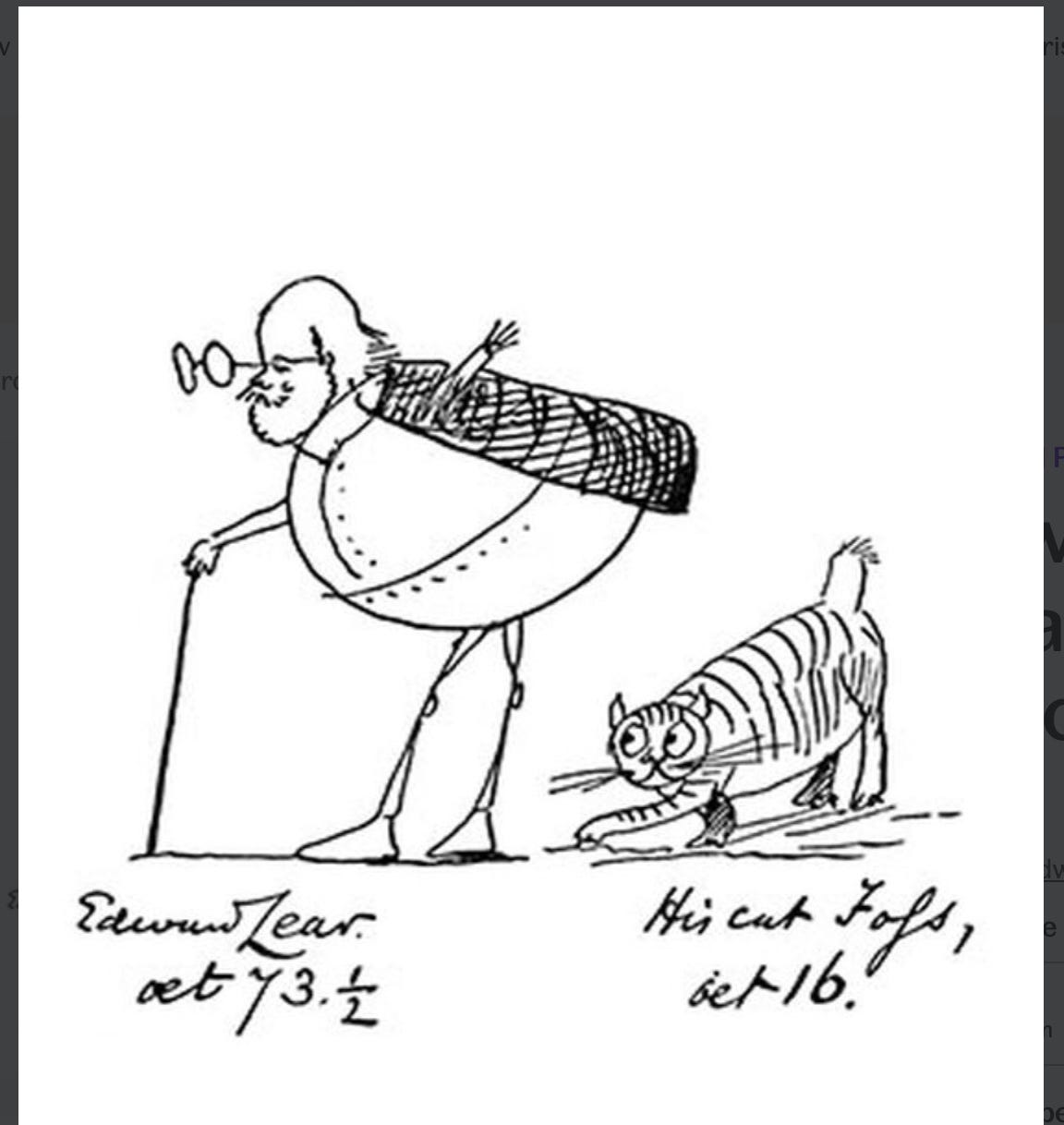

Nonsense a gift, nonsense his calling card, nonsense his ticket to making himself welcome as a nonplussed house guest way above his natural station. Nonsense with a provenance – nonsense ditties and drawings dashed off for nursery entertainment at Knowsley Hall while in artistic residence painting living specimens and skins from his great patron Lord Derby’s gobsmacking zoological collections, not yet twenty but already a nature illustrator of no small repute thanks to his surpassing Family Psittacidae plates. Just one of many commissioned artists and collectors present at the creation of the renowned zoo and archive at the Earl’s family estate, but the shambling young fellow soon becomes a household favorite, by day turning out enthralling watercolors of cranes and emus and lemurs and zebras and marsupials, and upon an evening regaling Lord Derby’s brood of grandchildren with his nascent nonsense. A busy recurring visitor from 1831 to 1837, when Lord Derby underwrites a long stay in Italy to launch his charge’s career in landscape painting. Two volumes privately published in 1846 that stand as a split-screen retrospective of those early golden years: Gleanings from the Menagerie and Aviary at Knowsley Hall, a handsome set of lithographic plates made from small selection of his original watercolors, and A Book of Nonsense, by Derry Down Derry, bound in two oblong octavo volumes. Indentical pictorial front-boards for both volumes, illustrated and hand-lettered by the author, the cover drawing a self-portrait of the jubilant Purveyor of Nonsense on tippy-toes bestowing his open book on an elated gaggle of nippers, one of them turning a somersault in glee. Inside, a grand total of 72 illustrated limericks on the recto leaf only, printed in lithography with the verses in italic capitals under the imprint of Thomas McLean, marked for purchase at 3/6d. And right there in script beneath the cover scene as a personal touch, a sprightly dedicatory limerick:

There was an old Derry down Derry,

Who loved to see little folks merry:

So he made them a Book,

And with laughter they shook,

At the fun of that Derry down Derry!

Derry Down Derry, who? A pip of a pen-name for the nonce, and a little inside joke – Derry down derry in all its reshuffled variants a common chorus in popular folk balladry, and like Hey nonny nonny a lyric device typically known as a nonsense refrain. A letter-perfect pseudonym to assume for A Book of Nonsense, just the persona for a nonesuch with a natural gift for the stuff, merely moonlighting in lunacy at present but already showing every sign of being a pastmaster at inimitable nonsense, a true-born laureate of nonsense for nonsense’s sake.

A Book of Nonsense a great success, nonsense his ticket to a growing following, and not just the little folks. A second printing in 1855 and a third edition, “new and enlarged,” in 1861, this time under his own name. And this time bedecked with an Original Dedication: “To the Great-Grandchildren, Grand-Nephews, and Grand-Nieces of Edward, 13th Earl of Derby, This Book of Drawings and Verses (The greater part of which were originally made and composed for their parents).” Away with the assumed character, along with any misconception that the infectious fun of the nonsense adept formerly known as Old Derry Down Derry was ever meant to be relegated to the nursery. No Nonsense Botany in evidence yet, and just a few traces of plant life getting in on the nonsense of the limericks, like the Old Lady whose folly induced her to sit in a holly and the Old Person of Dover who rushed through a field of blue clover. Those first nine nonsense flowers (all very rare) not coming to light until the nonsense bonanza of 1871-1872, back-to-back treasuries teeming with Nonsense Songs, Stories, Rhymes, Botany, Cookery, Alphabets, and More. Easy to get lost in the shuffle, true, what with all the classic numbers on tap – “The Owl and the Pussycat,” “The Jumblies,” “Calico Pie,” “The History of the Seven Families of the Lake Pipple-Popple,” plus more Nonsense Alphabets than you can shake a pointer at – but even so, worth its weight in lightfingered levity. All under his own name now to set the record straight, though he still can’t swear off the occasional turn as a nonsense double agent. Hence the impish headnote in the 1871 volume for the offerings falling under Nonsense Cookery and Nonsense Botany:

Extract from the Nonsense Gazette, for August, 1870.

Our readers will be interested in the following communications from our valued and learned contributor, Prof. Bosh, whose labors in the fields of culinary and botanical science are so well known to all the world. The first three articles richly merit to be added to the domestic cookery of every family: those which follow claim the attention of all botanists; and we are happy to be able, through Dr. Bosh’s kindness, to present our readers with illustrations of his discoveries. All the new flowers are found in the Valley of Verrikwier, near the Lake of Oddgrow, and on the summit of the Hill Orfeltugg.

Stop the presses! No other number of the Nonsense Gazette survives, alas, but there’s much to savor in this choice scrap of newsprint. Prof. Bosh, Dr. Bosh, name-brand bosh, bosh from the Ottoman Turkish bos, “empty,” introduced to English via J. J. Morier’s popular 1834 romance Ayesha, thereupon slang, chiefly British, for nonsense, stuff and nonsense, humbug, claptrap, blatherskite, what have you, another brand of name-brand nonsense. Professor Bosh, Doctor Bosh, our valued and learned contributor answers to either honorific and why not, renowned as he is the world round for his eurekas in the fields of culinary and botanical science, back again from his circumlocutions with a portmanteau of fantastic flowers native to the latitudes of Verrikwier and Oddgrow, smartly drawn and taxonomically correct for the edification of all bosh-loving botanists, that’s right, you heard it here first, exclusive to the Nonsense Gazette, bosh, all bosh, bosh but what bosh, all the nonsense fit to print.

ITEM

Angela M. Foster, Hands to Spell-Read-Write: Nonsense Botany. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; Large Print edition (2014)

This is the first book in the series Hands to Spell-Read-Write. It introduces American Sign Language (ASL) Manual Alphabet in a fun way of decoding the ASL handsigns into written words in order to learn the Nonsense Botany names. Children learning their ABCs will also have fun decoding the handsigns into letters and coloring the delightful illustrations. If you already know the ASL Manual Alphabet, then reading this book in just the handsigns would also be fun.

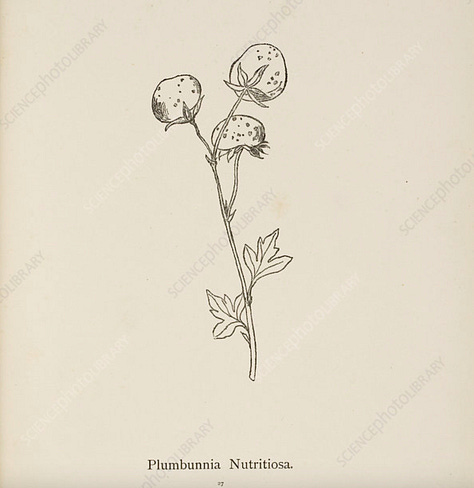

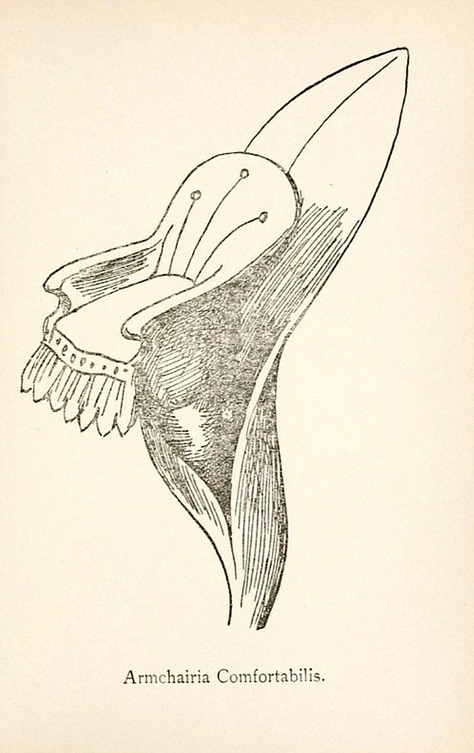

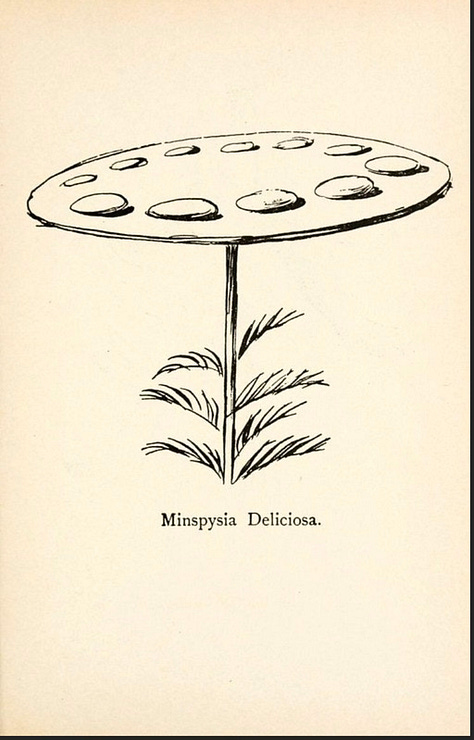

Plumbunnia Nutritiosa. Minspysia Deliciosa. Bassia Palealensis. Creature comforts. Good eats. A wee dram whenever you please. All growing wild, all for the taking. A nowhere out there in the ether, where I first saw them long ago. The Jumbly Islands a land of plenty, maybe another name for Lubberland, Cockaigne, the Big Rocky Candy Mountain. Here’s where the handouts grow on bushes, as the classic hobo song says. Go ahead, pluck a plum bun and a bottle of ale as you make your way, there’s more where they came from. Not a dreamland for wanton indulgence or indolence, mind you, closer to a kind of domestic arcadia, a market garden for a home sweet home. Local flora, one and all – Tureenia Ladlecum, Shoebootia Utilis, Washtubbia Circularis, Arthbroomia Rigida, Armchairia Comfortabilis. Nonsense botany, mere wordplay, but maybe as revealing a reverie as any on the good life.

All to amuse, to charm, to ingratiate, to make light, child-like. Tots to delight, cronies to regale, patrons to court, high muckamucks to disarm. Binomial nonsense, flowers to tickle the fancy, mostly running the gamut from zany to silly. How pleasant to know him, and he means to keep it that way. But how now, what’s this – a pair of botanical specimens on facing pages that don’t exactly smack of crowdpleasing whimsy. On this side, looking every bit the part, Phattfacia Stupenda, a bulbous visage glowering in a ruff of petals, haughty disdain written all over the monstrous countenance. No telling if it’s any particular Somebody, but you know the type – a stupendous brute of a bigwig boor fixing to throw some weight around, sucking up all the oxygen out there anyplace anytime. And on this side, just as in-your-face, Manypeeplia Upsidownia, a cluster of little flower-people hanging by their heels at the end of a long drooping stalk, gravity getting the better of them all. All suspended there, arms dangling straight down, in no position to do anything but twist in the wind. Who are these people? Who would want to find a stupefying mug like that in your flowerbed? It feels like there’s some subliminal spite afoot. Both specimens come off as more than a shade grotesque to sit comfortably under the heading of blameless nonsense. Charming stuff, nonsense botany, but it can’t get us back to the Garden. However pure or utter, there’s sure to be some worm in the bud. Some people – make that manypeeplia – are bad seeds. Some are festering lilies that smell far worse than weeds. Nonsense botany, disarming stuff, but there’s no missing the pong of misanthropy in the air.

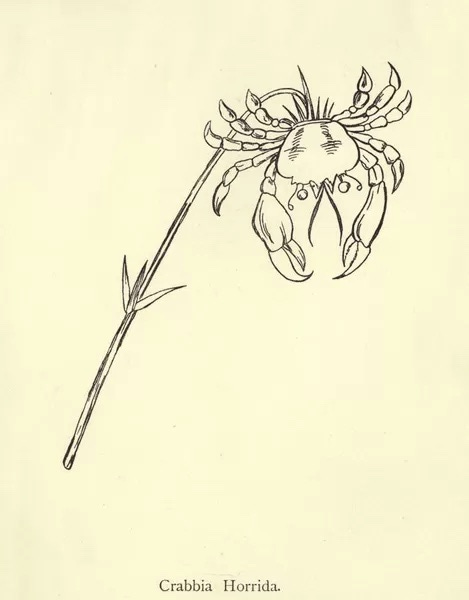

Not half-bad as a cod-botanist, knows his genuses, tends his own garden. Nasticreechia Krorluppia, a sprig of flowering caterpillars sprung up like some mutant snapdragon, or maybe an inside joke, a true flower the nasty creatures gobble up in no time flat, until all that’s left are their own creepycrawly humps and horns where the blossoming should be. Crabbia Horridia – horrid all right, one goonish crustacean fully sprouted and splayed like something out of Greek mythology or a Roman orgy, the hanging pincers big shears in search of little green thumbs. Nonsense chops working overtime, or maybe not – evidence points to first-hand knowledge on both counts. Nasty customers, those midsummer hornworms and the like, the bane of kitchen gardens everywhere. And the horrible horticultural crab? Maybe not nearly as nonsensical as you’d suppose. Dr. Bosh’s real San Remo garden known to boast many an exotic, including one native to New Zealand grown from seed sent by a sister, stunning to behold. Clianthus puniceus, something to write home about, the simile his, huge red flowers “like lobster’s claws – four bunches of them.” Clianthus, from the Greek kleios (glory) and anthos (flower), puniceus, borrowed from the Carthaginian, blood-red, reddish-purple, scarlet. Clianthus puniceus, common name kakabeak from the Maori Kōwhai Ngutu-kākā, also known as Glory-pea, Parrot’s Beak, Parrot’s Bill, and Lobster Claw. Clusters of waxy red flowers like lobster’s claws, the simile his but not his alone, listed online by the Royal Horticultural Society as Lobster Claw, evergreen scrambling shrub with pinnate leaves and spectacular claw-like flowers in spring and summer. Like lobster’s claws, like parrot bills, bunched scoops of flowers sometimes flamingo-pink but mainly fire-engine red or red like boiled lobster, flora from the bottom of the world like something you’d only expect to see in a book of nonsense, like wow. Nonsense in this case meaning part this, part that, mix and match, surf and turf, half in wonder, half in jest, bushes with beaks, shrubs with claws, shellfish grafted onto glory-peas, sea creatures growing on trees, one foot in one kingdom, one root in another. Nothing pure or sheer about it, kind of like the poet Marianne Moore’s imaginary gardens with real toads in them, nonsense meaning never having to say what you mean, nonsense meaning never say never.

[Second in a series]

Botanica Queeriflora: Notes Towards a Field Guide to Edward Lear’s Nonsense Botany

Part 1 https://postcardsfromthevolcano.substack.com/p/botanica-queeriflora