Notes Towards a Field Guide to Edward Lear’s Nonsense Botany (1)

How pleasant to know Mr. Lear!

Who has written such volumes of stuff!

Some think him ill-tempered and queer,

But a few think him pleasant enough.

Artist, illustrator, landscape painter, author, versifier, odd duck. English, the next-to-last of 21 children. Raised by his eldest sister, Ann, 21 years his senior. Dates: 12 May 1812 – 29 January 1888. Burly, bespectacled, beard like a gorse bush. Musician, composer, celebrated for his musical settings of Tennyson’s poetry, the only settings Tennyson tolerated, Tennyson the poet laureate for much of Queen Victoria’s epic reign. Prodigy, professional ornithological draughtsman at age sixteen for the Zoological Society of London. Specialty: Family Pissiticidae, Parrots. At eighteen, publishes imperial lithography folio of parrots drawn from life, the first of its kind, straightaway elected Associate Member of the Linnaean Society. Epileptic, asthmatic, melancholic, beset by “the Morbids,” tormented by the love that dare not speak its name. The Godfather of the Limerick, the Grandmaster of Nonsense, the One and Only Dreamer-upper of the Scroobious Pip and the Dong with a Luminous Nose.

Native Londoner, early years in what was then the leafy burb of Highgate. Second home of sorts at Knowsley Hall, the 13th Earl of Derby’s estate near Liverpool, first on a commission to draw birds and animals in Lord Derby’s famed menagerie, then at length in demand as impresario of the family nursery. An unfailingly painterly eye his meal ticket as a commercial artist for the smart set, specializing in scenic vistas. Habitual traveller or if you will wanderer, often abroad, business and pleasure, touring, sketching, sightseeing, scribbling. London, the Continent, London, the Mediterranean, London, some storied isle. Rooms in Rome, sojourns in Sicily and Malta, winters in Cannes and Corfu, peregrinations to Greece, Egypt, Dalmatia, The Alps, The Suez, Venice, Constantinople, Jerusalem, India, Ceylon. Across the Levant from Damascus to the Dead Sea, up the Nile as far as the first cataract. Run of travel journals brought out by assorted London presses – Views in the Seven Ionian Isles, Illustrated Excursions in Italy, Journal of a Landscape Painter in Corsica, Journal of a Landscape Painter in Southern Calabria, & c. Confirmed expat in later and last years, settles in San Remo on the Italian Riveria, has own home built, the Villa Emily, then purchases land to build another, the Villa Tennyson, named not for the poet but his dear friend the poet’s wife. Final resting place San Remo’s Foce Cemetery. Headstone honors a landscape painter in many lands … dear for his many gifts to many souls.

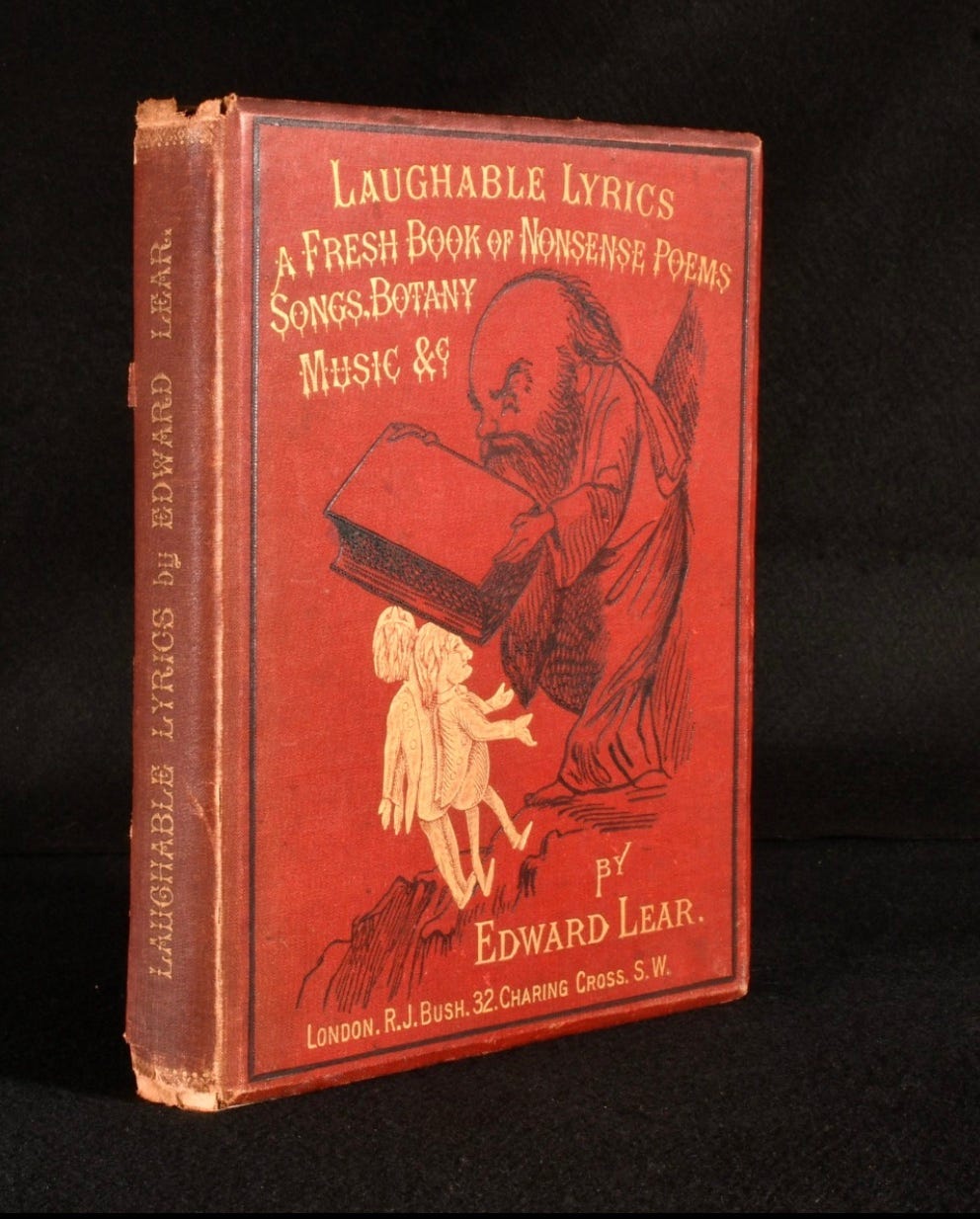

Nonsense Botany, series of droll sketches appearing in three omnibus collections under imprint of London publisher Robert Bush: Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets (1871), More Nonsense, Pictures, Rhymes, Botany, etc. (1872), and Laughable Lyrics: A Fourth Book of Nonsense Poems, Songs, Botany, Music, & c. (1877). First installment drawn in 1870 while staying in Nice and Certosa del Pesio in the Italian Alps: ten species brought to light in the spitting image of standard botanical folios, a line drawing roughly to scale with binomial Latin name as caption underneath. Verso, recto, visual, verbal, one specimen per page. Flowering plants, burlesque in bloom, hybrid quips and japes to see and say in sync, snip-snap, nosegays of binomial nonsense.

Nonsense Botany, running sight-gags, plants as puns, flowers to tickle the fancy, all in the thick of a glorious late flowering of imperishable nonsense. Period from 1869 through 1877 a procession of such volumes of stuff. “The Owl and the Pussy-cat,” debuting in the anthology Our Young Folks (Boston) in 1870, first of the canonical nonsense songs in print. Not one, not two, but three treasuries of fertile first-rate nonsense, containing among other fetching things the awesome alliterative alphabet “The Absolutely Abstemious Ass” and sterling nonsense songs “Calico Pie” (“Calico Pie, | The little birds fly | Down to the calico tree”), “The Jumblies” (“They went to the sea in a Sieve, they did, | In a Sieve they went to sea”), and “The Pobble who has no Toes” (“Nobody knew; and nobody knows | How the Pobble was robbed of his twice five toes!”). Stories. Songs. Pictures. Poems. Rhymes. Alphabets. Laughable Lyrics. Botany, Music, & c. All hail the Nonesuch of Nonsense.

Nonsense Botany, nonsense run rampant, springing up like wildflowers. First crop dating to 1870, written for English friends Mr and Mrs Bellenden Ker, chasing the sun in Cannes. Charles Henry Bellenden Ker the son of noted English botanist John Bellenden Ker, best known not for his treatise on orchids but the autodidactic Archaeology of Popular Phrases and Nursery Rhymes (1837). Nonsense Cookery, from previous year, also dedicated to the Kers. Nonsense the “breath of my nostrils,” he writes to another correspondent in 1870. And to yet another, the next January: The critics are very silly to see politics in such bosh: not but that bosh requires a good deal of care…. Nonsense in the air, a nose for nonsense, nonsense in full flower, a bumper crop of bosh, all bosh but what bosh, such bosh as only flourishes in the hands of a painstaking caretaker.

Nonsense Botany, a gift for nonsense, nonsense as a gift, a nonsense maven’s tussie-mussie by post. First unveiled in letter to Mrs. Ker dated 19 May 1870, from mountains above Nice:

As I know how fond you & Mr. Ker are of flowers, I have looked out carefully for any new ones all about the Grasse Hills, & have been fortunate enough to find nine sorts: – they are all very rare, & only grow about here, & in the Jumbly islands, where I first saw them long ago, – & as there happened to be a Professor of Botany there at that time, I got the Generic & Specific names from him. Unfortunately, the flowers all withered directly after I gathered them, so I made drawings of them on the spot, in order to send you a correct illustration of each.

A gift for nonsense, nonsense as a gift. All very rare, one specimen per page. Nine sorts, a correct illustration of each. Each one in trim profile by the book, each name supplied by a Professor of Botany, each illustration correct, one unerring drawing per page, binomial nomenclature in fine print. Nonsense, all nonsense, expertly executed binomial nonsense, botanical nonsense finely wrought, nonsense that can only be the child of knowhow.

First set, first page – Baccopipia Gracilis. Five tapering shoots, long and lean, the tallest one in bloom, the blossom one long-stem smoking-pipe. Long stem, funnel bowl, like something out of an oil by a Dutch master – Jan Steen, say, Steen’s “The Happy Family” (1668), the happy clan the very picture of merry dissipation, two young things toking on slender foot-long tobacco-pipes like old hands, girl and boy personifying the proverb on a parchment dangling from the mantelpiece reading So de ouden songen, so pijpen de jongen (“as the old sing, so shall the young pipe”). Pipe, from the Vulgar Latin pipa, “small reed, whistle,” hence “tube-shaped musical instrument.” Meaning “the sound of the voice” recorded by 1570s. Meaning “narrow tubular device for smoking” by 1590s. Gracilis, Latin for “slender,” sometimes Englished as “gracile,” customarily in physical anthropology – gracile as distinct from robust, as in the gracile early hominids Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus africanus, slender not in body build but in relative size of the masticatory apparatus of jaws, teeth, and chewing muscles. Not to be mistaken for a tobacco plant (Genus Nicotiana), indigenous to the Americas, Australia, Southwestern Africa, and the South Pacific, or for one of the world’s many grasses (Family Poaceae). Drawn on the spot, the tallest stem in bloom, the blossom the bowl of a single long-stem smoking-pipe.

First set, first facing pages – Bottlephorkia Spoonifolia (verso) and Cockatooka Superba (recto), both very rare. Verso specimen pictured tilting left, the blossom a bottle, possibly brandy or claret, encircled by a whorl of little upturned forks, likely fancy silverware but could be three-pronged pitchforks or even if you squint a matching set of tridents, all that plus leaves of spoons, soup-spoons if you had to guess, four spoons forking off the one stem at odd angles. Recto specimen tilting right, two stems in a V and a central stem keeling under the load of its budded corolla, a cockatoo with a flaring crest giving you the side-eye, the cockatoo a type of parrot but no longer a “true parrot” belonging to the parrot family Psittacidae, only just classified in 1840 by English naturalist George Robert Gray as subfamily Cacatuinae, a distinction lost to most but not to the Associate Member of the Linnaean Society who made his name as the superb illustrator of Psittacidae.

All very rare, fortunate to find them, found only about here and in the Jumbly Islands. Nonsense botany growing out of nonsense geography, nonsense geography giving rise to nonsense minstrelsy. See also: “The Jumblies,” dating from July 1870, being the verse chronicle of a voyage undertaken by seafarers of no great shakes but all kinds of pluck:

They went to sea in a Sieve, they did, In a Sieve they went to sea: In spite of all their friends could say, On a winter’s morn, on a stormy day, In a Sieve they went to sea!

The Jumblies, the Jumbly Islands, nonsense begetting nonsense. In a Sieve they went to sea, the Jumblies. Got to be the Jumblies of the Jumbly Islands, the happy isles where all those rare flowers are found. Got to be, but this nonsense shanty is all about the shipping news. In a Sieve they went to sea, they did, but will you look at that, in twenty years they all come back, in twenty years or more. But wherefore the islands, the Jumbly Islands, the happy isles where you can gather ye cockatoo-buds while ye may? You won’t get any fresh intelligence on nonsense geography or nonsense botany from this piece of nonsense minstrelsy. All there is to go on is the lovely lilting malarkey of the tape-loop nonsense refrain:

Far and few, far and few, Are the lands where the Jumblies live; Their heads are green, and their hands are blue, And they went to sea in a Sieve.

Far and few, far and few, the lands where the Jumblies live. Far and few, the only other clime where all those rare flowers grow. You can’t get there from here, and who would wish it otherwise? Better by far for it to be all jumbled up like this, lest things start to make sense.

Nonsense Botany, but not so fast. As there happened to be a Professor of Botany there at the time, I got the Generic & Specific names from him. Generic & Specific – adjectival forms of Genus and Species, terms that put the binomial into nomenclature. Taxonomy, the surpassing system for classifying everything in nature, two Latin names for everything, as if it were the most natural thing in the world. All Linnaeus’s doing, his great life’s work, still the gold standard in cutting-edge molecular biology. Linnaeus a force of nature, blazing the trail for science to sort specimens of all possible kinds and chart the evolutionary lineage of all living things. Linnaeus a physician and a zoologist but above all a botanist, botantical fieldwork his principal discipline, plant life classified by flowering sex parts his reigning obsession. Linnaeus not just a classifier in a category all his own but a thinker of stature, Linnaeus who in his 1751 treatise Philosophia Botanica argues that “the true beginning and end of botany is the natural system,” whereby “all plants exhibit mutual affinities, as territories on a geographical map.” Linnaeus the namesake of the Linnaean Society of London, founded 1778, for thirty years counting among its associates the precocious painter of Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1832), a full set of 42 hand-colored plates complete with generic and specific names, an imperial folio dedicated to Her Most Excellent Majesty and issued to acclaim half a lifetime before said artist would apply all that Linnaean know-how to a little something called Flora Nonsensica. Nonsense Botany, fantasy parroting taxonomy, taxonomy taking flight into fancy.

All names Latinized all due to Linnaeus, the name Linnaeus from lind in Swedish, the linden tree, the dead language alive and well as taxonomic lingua franca, outlandish as it sometimes might sound. Only two names now, gone are the days of polymorphously perverse polynomials when the flower otherwise known as baby’s breath went by nothing less than Caryophyllum saxatilis foliis graimineis umbellatus corymbosis. Every name a neat and tidy twin-bill now, no matter how polyglot the flower market – Gypsophilia (“chalk-loving”) fastigata (“parallel, clustered, erect, reaching skyward”), nothing to do with babies or breathing or gypsies or fasting, nothing to leave you short of breath, baby. Neat and tidy, makes perfect sense. Drawn .on the spot – Pollybirdia Singularis, the petals a pinwheel of five roosting parrots, the corolla a five-point polygon atop a stalk at a slant, all in pen and ink but plenty flashy all the same. Nonsense taxonomy by way of oxymoron, proposes biographer Sara Lodge, “in that it contains literal ‘pollys’ (parrots) and figurative polymorphosis; it is ‘singular’ (odd) and plural at the same time.” Latin the name brand for no such thing, polyvalent as you please. Neat and tidy, makes perfect nonsense.

[First in a series]

Botanica Queeriflora: Notes Towards a Field Guide to Edward Lear’s Nonsense Botany