The word means exactly what it sounds like it means. It’s an Old English word that means the same thing in modern English. A compound noun, a word made out of two words smushed together. A word made out of two common words to make one cryptic word. A word made out of two familiar words to make a word you’ve never heard of.

The word in Old English is wordhord and it means what you’d figure it means – a hoard of words, a cache or stash or stockpile of words. Old English word from the Proto-Germanic wurda, “speech, talk, utterance, statement, report, news.” Old English hord from from the Proto-Germanic huzdam, “treasure, hidden place, buried treasure.” A hoard of words, a trove of words, words concealed in one place, words for safekeeping, a treasury of things to say. Two everyday words, one arcane word. A word made out of two readymade words that sounds like it must be a made-up word.

What sorts of words were stored in the word-hoard? Special words. Stirring words. Cunning words. Words that were only used on certain occasions for certain reasons. Words that only someone who knew the combination to the word-hoard could use.

Only a select few knew. The keepers of the word-hoard were the Anglo-Saxon scops, and they kept the word-hoard in their heads. They were poets, oral poets, the makers of lays, the singers of tales. The special words in a well-stocked word-hoard were nothing less than the words that made poetry poetry, the words that made words sing. The poets kept the word-hoard in their heads, and the words were the tools of their trade. The word-hoard was the exclusive inventory of words for the standard repertory of sanctioned things for the keepers of the words to sing. Only poets knew how to help themselves to the word-hoard because only poets knew the words by heart.

Special words. Storied words. Crafty words. Loaded words, one-of-a-kind words, words out of this world. Words that cast a spell. Words that work like charms. Words like whale-road, world-candle, battle-light, weaver-walker, bone-locker. Words like word-hoard, fancy that.

The original old-school word for words like word-hoard is kenning. From the Old Norse kenna, “to know,” to know in all kinds of ways, “to know, to recognize, to understand, to feel or perceive, to describe, to call, to name.” A kenning a special kind of knowing-by-naming, a stylized figure of speech in Old Norse and Old English poetry, one freighted word made out of two innocuous words as a signature means of metaphor-making. Special words with special powers, a specialty of Anglo-Saxon oral poetry, a declaiming scop’s spiffy device for transfiguring the sea into whale-road and the sun into earth-candle in no time flat. Every kenning a tool of the trade, all the kennings locked up for safekeeping in that storehouse of kennings known as the word-hoard.

But that was then, and this is now. Whatever happened to the word-hoard? Where are the kennings of yesteryear? Long gone and hard to find, relics of a dead tongue from a lost world. The stockpile has become a scrapheap, the storehouse a haunted ruin. The whole operation had a good run, but it’s been out of commission for a millennium or so. All that survives of Anglo-Saxon oral culture is all that survives in a bedraggled handful of medieval monastic codexes, and there’s no telling how much the scribes may have been salvaged. All that’s left of the words the poets kept in their heads are ghosts in our machines.

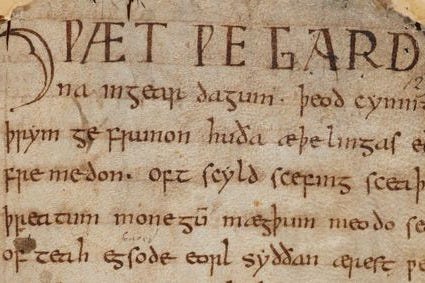

But a funny thing happened on the way to oblivion. Kennings never really wasted away, they just stuck to their knitting by any other name. The word-hoard never really closed up shop, being a metaphor for a poet’s memory bank all along. It’s also the case that the word wordhord has come down to us intact as text, even if just by the skin of its teeth. In her enlivening 2022 book The Wordhord: Daily Life in Old English, medievalist Hana Videen does the math – wordhord appears precisely seven times in the extant corpus of Old English literature, each time in a passage of poetry. A grand total of seven times, always in a work of verse, most notably in the grandest remnant of all:

Him se yldesta ondswarode

werodes wisa, wordhord onleac…

The scene: Lines 258-259 in the Beowulf epic, the Geatish warrior Beowulf parlaying with the watchman at the Great Hall of Hrothgar, King of Denmark, the great warrior here on a mission to slay the monster Grendel. The watchman on the wall demands that Beowulf state his business, and Anon the poet steps in for two terse lines of stage directions:

The leader of the troop unlocked his word-hoard;

the distinguished one delivered this answer…

Unlocked his word-hoard – that’s Anon as translated by Seamus Heaney, the Irish magus faithful as ever to the flinty alliterative economy of the text. Videen notes that wordhord is hitched to onleac in four of those seven instances, a small sample size that might still suggest that it’s not a bug but a feature of the oral-formulaic method. Even so, it’s worth speculating whether Anon is overplaying her hand here. Beowulf’s answer is his letter of introduction, long on exposition and information. Unlocking his word-hoard makes it sound like the distinguished one is reaching into his bag of tricks rather than distinguishing himself by speaking his mind.

Then again, maybe that’s taking the double-duty metaphor a little too literally. Based on the rest of Videen’s annotated examples, unlocking your word-hoard wasn’t like rifling though your kit bag for the killer kenning. It was also a way of saying someone spoke wisely and well, and it wasn’t just poets with a skeleton key handy. In the poem Andreas, it’s said that the eponymous St. Andrew “wise in understanding, unlocked his word-hoard.” In The Metres of Boethius, it’s Wisdom personified who “unlocked her word-hoard again, sang her own truths and spoke thus…” In fact, the only surviving reference to the craft of poetry appears in the first line of the poem Widsith, where the itinerant scop of that name unlocks his word-hoard as he launches into his braggadocious traveller’s tale in alliterative verse. If the legendary wordhord of the Anglo-Saxon oral poets can be likened to “almost a language within a language,” as Michael Alexander puts it in The Earliest English Poems, the ensuing spinoffs in translation have left us with a rebooted word-hoard that’s far less poetically proprietary than the archaic prototype.

In theory, anyway. The word-hoard never really closed up shop, but as a going expression it hasn’t exactly done a brisk business outside of rarefied academic circles. Up until fairly recently you could be a literary Anglophone up to your eyeballs and never have it swim into your ken. It’s probably safe to say that no great number of modern poets would catch the allusion either, except perhaps among those brought up in the latitudes where Anglo-Saxon was once in the air. More than a few of the rest of us may have first come across it as a kenning lurking near the tail-end of the title poem of Heaney’s 1975 collection North, one of the few choice words for the north-haunted poet spoken by a Viking warship’s “swimming tongue.” The ghost-vessel has a message, and it comes in the form of a stringent writing assignment:

It said, “Lie down

in the word-hoard, burrow

the coil and gleam

of your furrowed brain.

Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

in the long foray

but no cascade of light.

Keep your eye clear

as the bleb of the icicle,

trust the feel of what nubbed treasure

your hands have known.”

The tenor of the gesture is pure Heaney – a long walk across the crashing strand bringing on a summons-by-apparition from the ocean primeval, the language dense with the cumulative stratum of clashing tongues and creeds. So it follows that the task at hand calls for nothing so matter-of-fact as merely unlocking the word-hoard, not at this late date. The spectral instructions couldn’t be more explicit – the tall order here is to lie right down in it and go deep. As with the old oral poets toting around the word-hoard in their heads, it’s all there in the gray matter and it’s the only way you’re going to get anywhere. It’s all there in the word-hoard, and by now there’s so much more buried there that you’d better be ready to work in the dark and go by feel.

If Heaney’s latter-day word-hoard comes off as more fiendishly inaccessible than ever, Videen’s The Word-Hoard sets its sights on a far more user-friendly model. Her bright idea is to flip the catchphrase on its head, swapping out the lockbox wordhord of the scops for an open-door word-guide to Daily Life in Old English. That means many an otherwise mundane word that wouldn’t have made the cut in the wordhord of old can now have its day in the sun as a word worthy of special notice. Videen turns out to be an infectious cheerleader for Old English and a wordhoarder of long standing herself, going back to 2014 when she launched her own word-a-day Old English Word-hoard blog as a postgraduate student at King’s College, London. The first word she tweeted out was her favorite Old English word of them all – wordhord.

Some of the words in Videen’s word-hoard may have been humdrum in their prime, but her hashtag unearthings reliably give off a newfound gleam. She has a fine knack for digging up long-gone words for things we still don’t really have words for, words like #ūht-cearu (“care that comes early in the morning”) and #hyht-gifua (“gift which causes hope or joy”). There’s also the occasional whopper with literary fingerprints all over it – see #fastitocalon, “a large whale that tricks sailors by appearing to be an island.” Then there are words that blow your mind for not being remotely obsolete whatsoever. The word word is just such a word, a word that’s gotten around all this time without aging a whit.

If there’s one word here that leaves you wanting more, it’s that very word word. It belongs and it doesn’t belong. It means what it’s always meant. Its past isn’t dead, it’s not even past. It begins to feel like the odd word out. For all its instructive delights, Videen’s repackaged word-hoard largely remains the erstwhile name-brand wordhord in so many words. The word-hoard as a figure of speech in a sense, but mainly as a rubric for a standard lexicon listed word by word. A textbook case of something done before under the same title – here’s a scholarly citation for Stephen A. Barney’s Word-Hoard: An Introduction to Old English Vocabulary (Yale 1985), comprising “a vocabulary of some 2000 words drawn from the poems that beginning students normally read.”

Same word, same title, and the same scholarly liberties taken – turning the strongbox word-hoard into a big tent for Old English vocabulary writ large. Nothing untoward about that, but it’s still sure to be a word-hoard that locks a lot of us out. Leaving it at that would be the worst of both worlds – a word-hoard that can’t be what it once was, and won’t be all that it could be. Word has it that English grew up to be possibly the most word-welcoming, word-hoarding tongue under the sun, but there’s no extending the evolutionary metaphor if you stop the clock when Grendel’s carcass was still warm. Word to the wise: a word-hoard that’s just a wordhord is no word-hoard at all. That was then and this is now. It’s too good a word to let go of.

Too good a word and too opportune too to let it slip away. Too opportune a word not to seize on as a newfound term of art for coming to grips with the bedeviling signs of the times. It’s not too good to be true – the Old English wordhord falling into place as a stepping-stone to a whole new state-of-the-art word-hoard, and none too soon.

To be continued