Everyone knows things are bad these days, but how bad? So bad it’s hard to keep tabs on all the bad blood and bad faith, all the bad actors and bad apples, everything going from bad to worse.

So bad we need a whole new metric.

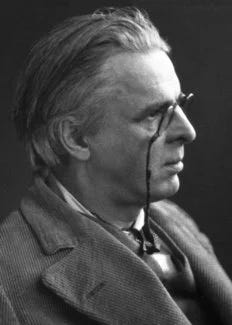

Wait, we’ve already got one. Back in the summer of 2018, when things were bad but not this bad, waggish Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole came up with a novel unit of measure – the Yeats Test. “The proposition,” he wrote in the Irish Times, “is simple: the more quotable Yeats seems to commentators and politicians, the worse things are.”

That would be William Butler Yeats – the superstar Irish poet and magus of letters, 1923 Nobel Laureate and self-proclaimed “king of the cats.” O’Toole nails it, and he’s not just stanning on a national treasure. He’d been tracking the spike in Yeats quotes like a stock ticker all across the Anglosphere punditocracy. He could make his case on the strength of Yeats’s “magnificently doom-laden” poem “The Second Coming” all by itself.

You know the one. Even if you haven’t read the thing since junior high, you’ve heard its killer catchphrases who knows how many times – Things fall apart, the center cannot hold, what rough beast, and slouching toward Bethlehem, for starters. They’ve been in heavy rotation as go-to commentariat commonplaces for roughly a century now, and still show no signs of conking out.

Everyone knows it. Things fall apart. The center cannot hold. Break out the Yeats Test.

O’Toole holds there’s nothing like it for getting a read on how bad things really are out there. He’d been doomscrolling, and he had the clicks to prove it:

“The centre cannot hold” was tweeted or retweeted 499 times on June 24th, 2016, the morning after the Brexit vote. Thereafter it continued to appear 38 times a day. It also appeared 249 times in newspapers in the first seven months of 2016…. And of course “Things fall apart” over and over. Other phrases from The Second Coming, like the “rough beast” (slouching towards the White House) have been called into service. The most frequent triggers for these quotes in 2016 were the Paris and Brussels terror attacks, the rise of Trump and the Brexit vote. But continuing global instability and the sense of foreboding it induces have made Yeats’s apocalyptic vision as quotable as a chart-topping song.

So what exactly makes the Yeats Test such a trusty barometer of bad times? O’Toole chalked it up in part to “the way great phrase-making acquires a timeless quality,” but he figured there’s got to be something more Yeats-specific to it. It must have to a lot do with Yeats’s war-torn times, he ventured, and even more to do with “his poetic antennae picking up the distress signals” on all fronts. “His brilliance,” O’Toole reckoned, “lay in his ability to turn these immediate anxieties into words that seem capable of articulating every kind of epic political disturbance.”

Might as well call it a Celtic spidey-sense. Things fall apart; the center cannot hold. Everyone knows it’s true. Whenever bad things start going down, there’s Yeats to tell us he told us so. His dead-on turns of phrase have a life all their own.

And here we are, seven years on. Things are bad, but the question is how bad. How bad, and how much worse it could get. Time to break out the Yeats Test again, but is it still up to snuff?

Even as he was first putting it out there, O’Toole himself was none too sure. He fretted that with the bull market in bad news, all those chart-topping Yeats lines were “in danger of sinking into the linguistic mire of cliché.” That would make it a Yeats Test of an entirely different order, a grim formula for calculating the rate at which great poetry dies an excruciating death by a thousand quotes.

Quite the sticky wicket. O’Toole proposed a reboot. To keep the Yeats Test in good nick, it was time to up our game. “We need to renew the store of Yeats images that seem to comment on our times,” he urged, and got things rolling with a cut-throat quatrain from the poem “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen” that in his view “says it all about fake news and the pre-fascist culture of hatred”:

We, who seven years ago

Talked of honour and of truth,

Shriek with pleasure if we show

The weasel’s twist, the weasel’s tooth.

Good one, fine and damning as they come. Maybe just the thing when the duly elected weasels run rampant. Then again, probably not – not terribly quotable in the public square, a bit too much of a slow burn in the heat of the moment. O’Toole had come to the tail-end of his column anyway, and he was really just spitballing. It’s two presidential cycles ago, donkey’s years in political commentary. Things still fall apart, but it’s starting to feel like the Yeats quote-quotient isn’t the geopolitical pressure gauge it used to be.

So here we are. Things are bad and everyone knows it. Bad, but how bad? Maybe it’s time to break out the Yeats Test, or maybe it’s time for a whole new metric after all. An updated test, an upgraded readout, a next-gen index for calibrating how bad things really are.

Easier said than done. The beauty of the Yeats Test is its streamlined simplicity. Simply put, the more quotable Yeats seems to commentators and politicians, the worse things are. Good luck finding an alternative half as legit with anything like the same longevity. It would have to be someone who’s a decent match for Yeats’s all-purpose quotability. It would have to be someone in the same league at picking up on the rumblings of all the things falling apart.

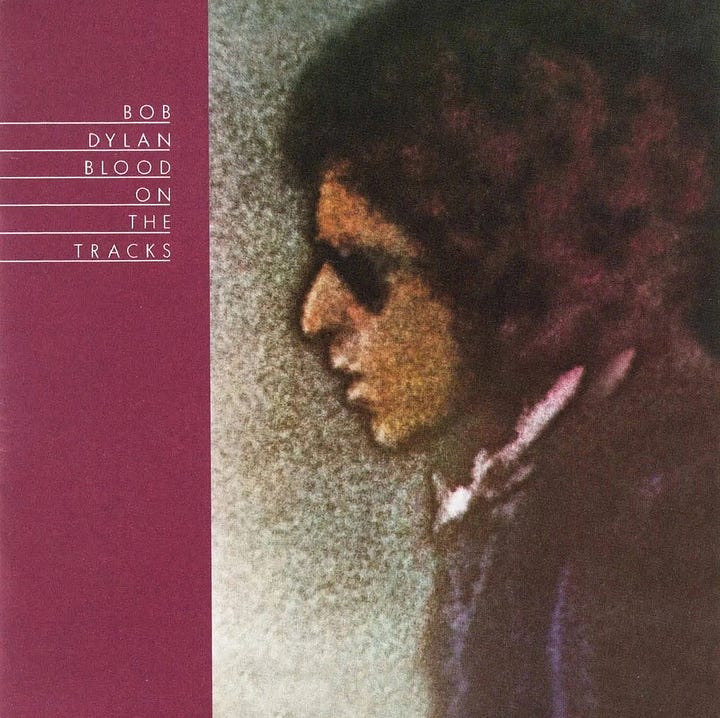

Only one real contender comes to mind. A Nobel Laureate like Yeats, if in every other way a whole other breed of cat. A bard who took on the name of another bard. Not a poet per se, but a true troubadour with an epic history of quotability. A troubadour with an ear to the ground and vision to burn.

Dylan, Bob Dylan.

Bob Dylan, born Robert Zimmerman. Bob Dylan, his adopted surname a shout-out to the meteoric Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

Bob “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” Dylan.

Bob “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” Dylan.

Bob “Like a Rolling Stone” Dylan.

Bob “All Along the Watchtower” Dylan.

See, the guy can hold his own in a zeitgeist quote contest on the strength of his song titles alone.

Bingo, time to break out the Dylan Test. Only not so fast, it’s no simple matter of swapping out one for the other. Dylan is no Yeats and Yeats is no Dylan, even if it sometimes seems they’re sending out red-alerts on the same wavelength. Like when Yeats said in 1916: The line it is drawn | The curse it is cast … And the first one now | Will later be last | For the times they are a-changin.’ Like when Dylan said in 1964: All changed, changed utterly: | A terrible beauty is born.

Whoops, other way around. Yeah right, as if for a heartbeat it could be a case of mistaken identity. Forget about retrofitting the prototype – as in, the more Dylan you hear quoted in the media of record, the worse things must be getting. Things fall apart; mere correlation cannot hold. It won’t fly to simply reset the dial.

A modest proposal, if I may. Introducing the Dylan Scale.

Not the Yeats Test 2.0, another metric altogether for sussing out how bad to the rotten core all the bad mojo is getting to be.

The Dylan Scale, modelled loosely on scales for indexing forces of nature like the Richter for earthquakes and the Beaufort for wind-speeds, scales for rating degrees of intensity and levels of mayhem.

The Dylan Scale, a scale for tracking bad vibes in exponential orders of magnitude, all the bad faith and bad blood in the world going from bad to worse.

The Dylan Scale, reverse-engineered for pattern recognition in the course of human events, geared for getting a reading on all the ways history doesn’t repeat itself but often rhymes.

Are things really that bad? Time to break out the Dylan Scale.

Timing is everything. Dylanology is back in the spotlight big-time. Timothée Chalamet’s chameleonic star turn in James Mangold’s touted 2024 biopic A Complete Unknown (the title a lopped-off simile from the simile-slinging 1965 kiss-off smash “Like a Rolling Stone”) has sent shares in Dylan futures to highs not seen since he took home the 2016 Nobel in Literature. It’s the perfect time for a hot-button trial run.

Now comes the fun part. Like the Yeats Test, the Dylan Scale ought to be a user-friendly DIY dashboard for general circulation, no strings attached. No Bob-core Dylanologists at the table, please. It’s not some Dylanometer app coded to aggregate track-samples overdubbed to the drumbeat of late-breaking bad news.

That would be rad, but this here Dylan Scale runs on sheer chutzpah and works strictly by feel. You can be a mere buff or even a newbie wet be.hind the ears. You don’t need to know when Dylan went electric or which hurricane the song “Hurricane” is about. All you need to do is tap into the Official Bob Dylan Site and go for a spin.

It’s not a test, it’s a scale. It’s adjustable, it’s adaptable, it comes with multiple settings. Go ahead, program your own customized version. You can set up your own system of weights and measures. Your own Dylan Scale for keeping tabs on what you will.

Me, I’ve got Dylan ballads and blues on the brain. Hold on, make that hardhitting choruses and heatseeking refrains. My DIY Dylan Scale is built to home in on shadows and echoes, not issues or causes. It’s got a conversion table for things like dreams deferred and wolves at the door. It doubles as a playlist for doomscrolling.

DIY means DIY, I tell you. You might be envisioning a Dylan Scale designed to monitor the vital signs of the body politic, useful for administering yourself a civic stress test. Handy-dandy, you cue up the iconic early protest anthems – “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” “Masters of War,” “Chimes of Freedom,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” – to get a fix on how the arc of history is bending sixty years on.

Makes perfect sense, but that’s not how mine works. I’ve rigged up my Dylan Scale to function as a bespoke gutcheck-tracker and homemade soulsickness detector rolled into one. I’ve jiggered the thing to chart the shocks to my system and the ground moving under my feet. I’ve devised my own Dylan specs to size up how badly I’ve got them, the Subterranean Homesick Blues, the Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues, the Tangled Up in Blue Blues, the It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue Blues. How bad a case I’ve got of the creeps, the shakes, the willies, the bends.

See, that’s where all the choruses and refrains come in. They’re my units of measure, my degrees of magnitude. They keep coming round with the same chord changes and rhyming lines, but never landing the same way twice. Sometimes it’s a shift of phrase, sometimes a slant rhyme or a bent note, sometimes a vocal rasp or verbal riff launching a banshee mouth-harp wail. Here it comes now, and there it goes again. Never landing the same way twice, but somehow always hitting me where I live.

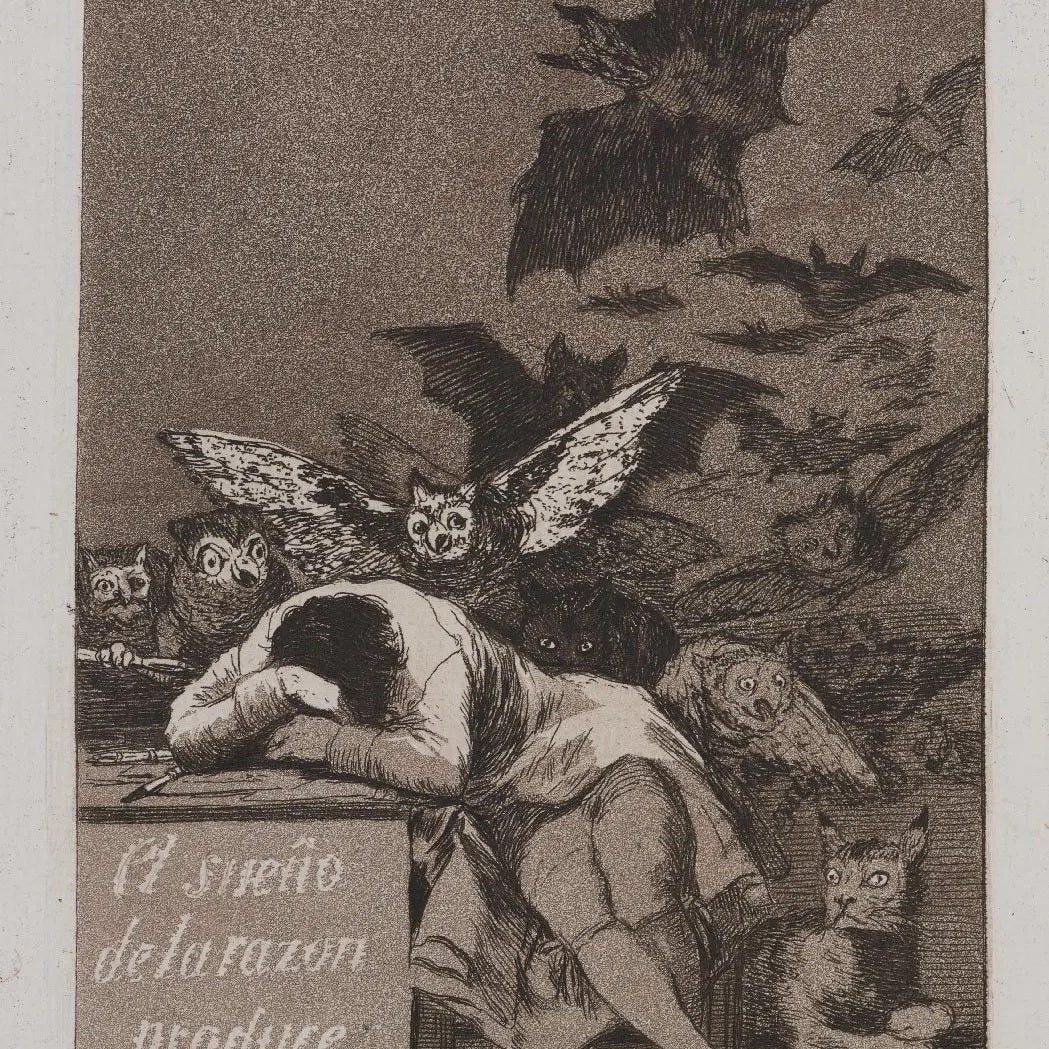

Refrains and choruses, reliable and mercurial. That’s the way a Dylan ballad or blues number usually rolls. It does its own thing by tapping into the deep dark wells of folk balladry and oral poetry, entwined traditions founded on the first principles of repetition and variation. It’s all about timing and the feeling of something happening again, moving the needle time after time. It’s all about everything that goes around coming around. Here it comes now, and there it goes again: And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, and it’s a hard | And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.

Reliable and mercurial, time after time. Repetition and variation, practiced devices for channeling primal forces. Dylan has been a genius at it from the first. (So was Yeats, by the bye, but that’s a thesis for another day.) Chorus and refrain, anaphora and litany, the repeating line that flips the script or steals a march. The chiming phrase that changes things up a little or a lot every time. The beaten track of a ballad stanza or blues hook turning into a path not taken or then again the other way around. Right on cue but like it’s out of the blue, the hard, the hard, the hard rain that’s a-gonna fall.

That’s the beauty of the Dylan Scale. That’s the great thing about my customized model. It’s not your old-school Misery Index. The lyrics rock, but it’s not really about what the lyrics are about. It has much more to do with the way the refrains keep landing and the raw nerves they’re always hitting. It’s not about anything topical, it’s something about the timing and the sinking feeling of everything falling apart in real time. Something about the times trying our souls, the past-is-prologue and the only-time-will-tell of it all.

It must be something about the way I’m wired. I’ve been listening to those choruses and refrains for so long it’s like they’re hooked up to my limbic system. They’re my units of measure, my degrees of magnitude. They can tell me my exposure levels to radioactive angst and animus. They can give me an EKG score for loss of heart. I can plot my standard deviation from the zero-sum dystopian mean. I can see where I fall on the it’s-a-hard-it’s-a-hard curve of picking myself up and dusting myself off.

Reader, I’ve just taken my latest reading. My Dylan Scale has spoken. The times they are a-falling apart, but you knew that already. The center it isn’t holding, but that’s hardly a scoop. The Yeats Test still works, but it’s high time for a new metric.

DIY means DIY. Your results may vary. I’ve configured my Dylan Scale to rate my tolerance threshold for the whole bloody shitshow. Bad times multiplying by orders of magnitude. The broken record of bad news about the bad doings of bad seeds. All the bad signs I can feel in my bones, gutting me where I live.

Nothing against the Yeats Test, but the dire hour calls for the Dylan Scale. Sometimes I doomscroll on Shuffle Mode. Sometimes I get a bad feeling history isn’t repeating itself but rhyming something fierce. Something tells me things they are really a-falling apart this time.

The Dylan Scale: A Doomscrolling Playlist