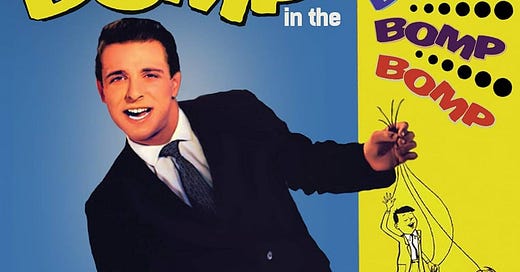

Who put the bomp in the bomp, bomp, bomp?

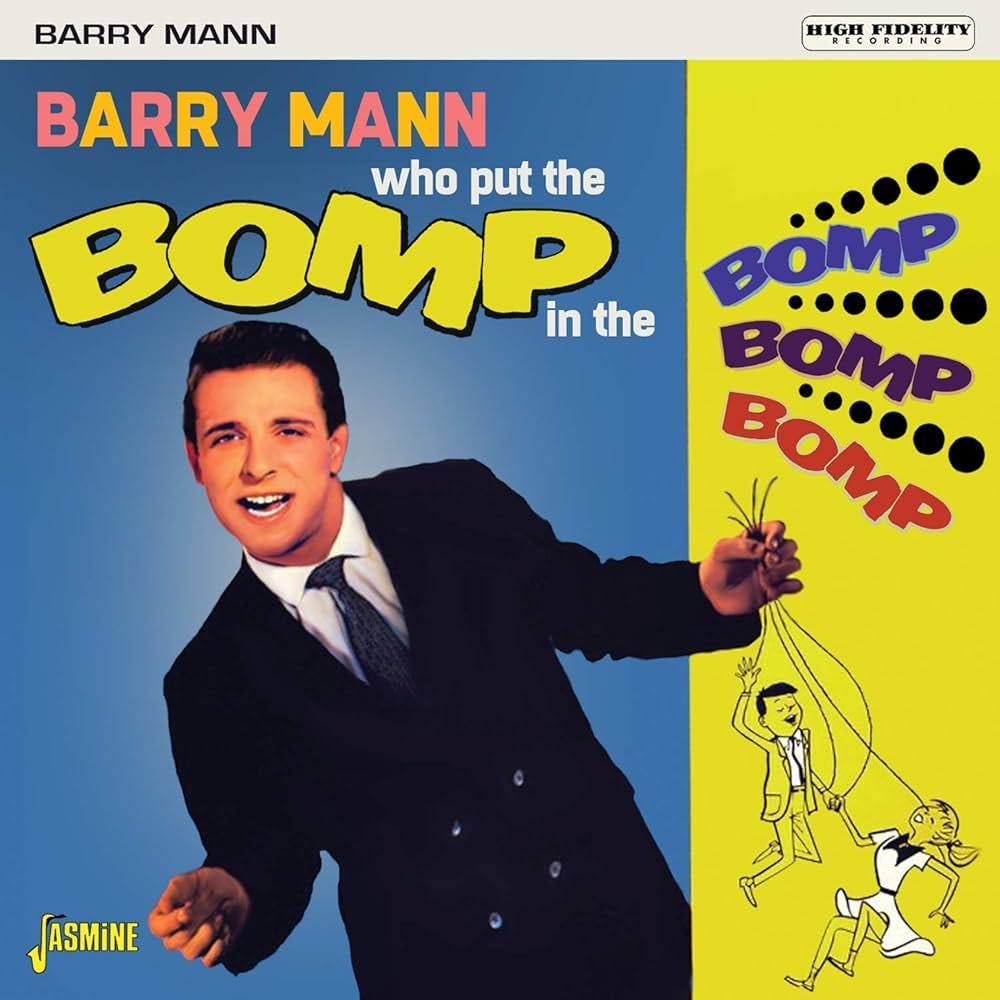

It’s a freighted existential question right up there with how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Spoiler alert: nobody knows. When the Brill Building songwriting team of Barry Mann and Gerry Goffin released their hit single “Who Put the Bomp” in 1961, they were just putting a doo-woppy new spin on an eternal mystery. Everybody knows nobody knows who put the bomp in the bomp bomp bomp, just like nobody knows who put the la in fa-la-la or the nonny in hey nonny nonny.

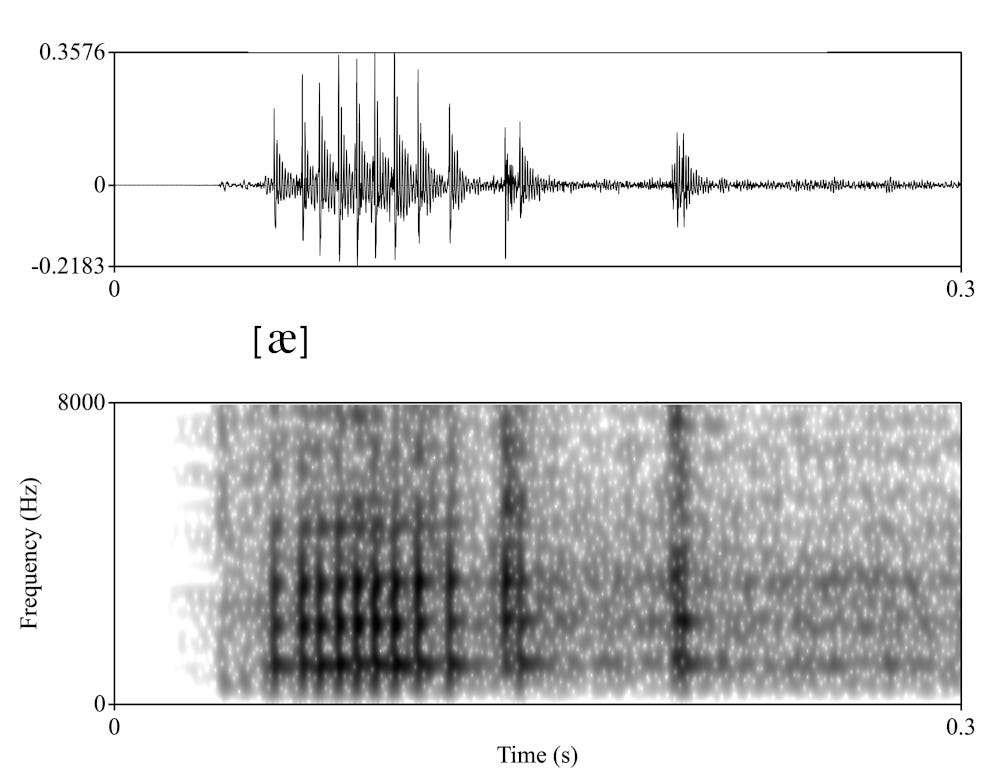

Linguists call them “non-lexical vocables.” The rest of us can get by with calling them nonsense syllables or just plain gibberish. They’ve been around forever, or at least since our chatterbox ancestors swung down from the trees. They mean nothing and they tell us everything we need to know. Our tongues would be tied without them.

Who put the bomp in the bomp bah bomp bah bomp? Who put the ram in the rama lama ding dong? Short answer: songs, vocals, the singing voice the world over. Trad ballads, old-school madrigals, hymns and chants of all stripes, pop crooning and scatting all across the dial. Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, Yodel-ay-ee-ooo, Do-re-mi, Da-doo-run-run – those nonsense syllables are the air we breathe, the vocables of the spheres. They’ve been around forever, and they’ve never gone away.

Sometimes these days they come streaming back. You couldn’t miss them on last week’s playlist tributes to genre-straddling pop prodigies Brian Wilson and Sly Stone, both dead at age 82 after blowing the doors off the music industry while still twentysomethings. Dreaming up runs of nonsense syllables to groove on probably wouldn’t make it onto either savant’s short list of signature chops, but when the spirit was willing they could really shoot the works. You could even argue for their place in the pantheon on the strength of just one milestone side apiece.

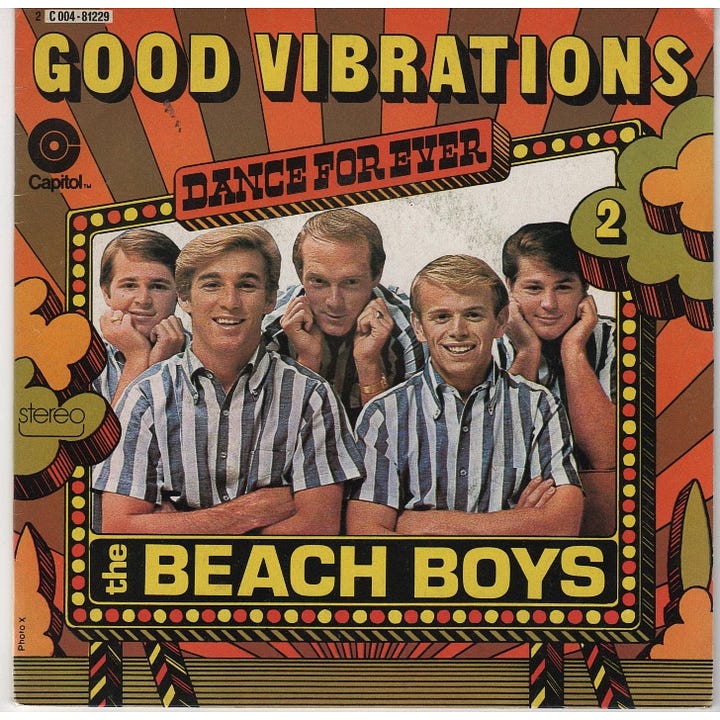

Flashback: Brian Wilson’s 1966 studio masterwork “Good Vibrations,” by general consent the greatest of the Beach Boys’ greatest hits. Instant classic, psychedelic sonic boom, multi-session mixing-board miracle. The “pocket symphony” Wilson would call “my whole life performance in one track.” A chart-topping harmonic convergence greater than the sum of its over-dubbed multi-track parts, surf music meets Mozart.

All that, and a seraphic chorus of non-lexical vocables too. Even in the thick of all the orchestrated muchness, they somehow more than hold their own. Not that you’d know it from just side-eyeing the lyric sheet:

I’m pickin’ up good vibrations

She's giving me excitations (oom bop bop)

I’m pickin’ up good vibrations (good vibrations, oom bop bop)

She's giving me excitations (excitations, oom bop bop)

Good, good, good, good vibrations (oom bop bop)

She’s giving me excitations (excitations, oom bop bop)

Good, good, good, good vibrations (oom bop bop)

She’s giving me excitations (excitations)

It looks like gibberish on the page, because on the page it is gibberish. Three nonsensical syllables, that’s it. Oom bop bop, in parenthesis no less. It sounds like baby talk, and it’s all of a piece. Rattling off good after good sounds like a bad joke. Excitation is not a word.

And look, the Outro is a total meltdown. Bops are wild. The goods are gone, along with all the nouns. Not a word to be heard. It’s na na and do do, over and out:

Na na na na na, na na na

Na na na na na, na na na (bop bop-bop-bop-bop, bop)

Do do do do do, do do do (bop bop-bop-bop-bop, bop)

Do do do do do, do do do (bop bop-bop-bop-bop, bop)

Say it out loud, and you sound like a half-wit. Say it out loud, and you’re doing it wrong. The only way it makes sense is when it’s sung. Only then will nonsense syllables take wing.

That’s how it’s been since the world was young. The non-lexical vocables making waves in “Good Vibrations” echo down the ages. They’ve been known to make for the best good vibes. Oom bop bop, Oom bop bop on repeat, one more catchy volley of nonsense syllables in the untold dynastic line of Tra-la-las, Yippie-ki-yays, Derry-down-downs, and Doo-wah-diddys. On repeat, but with a tempo and a beat, the dum-de-dum rhythms of nonsense choruses and nonsense refrains. If you want them to mean something, you’ve got to lend them your ears.

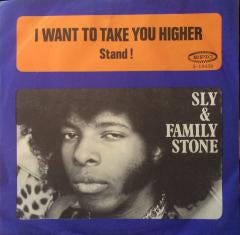

Next in the queue: Sly Stone’s 1969 funk-rock anthem “I Want To Take You Higher,” originally a B-side but immortalized as the turbo-charged highlight of Sly and the Family Stone’s pre-dawn set at Woodstock. Electrifying performance, booty-shaking freedom joyride, a groove to run a power grid on. Peak Woodstock, peak Woodstock Generation film clip, peak Afro-haloed Sly shredding on keyboards in blazing white raptor-feather fringes like some incandescent astral being. The title refrain recycled from the Family Stone back catalogue but taking on a life of its own as a call-and-response hippie-gospel mantra, inevitably recycled again for Jeff Kaliss’s 2008 Sly Stone bio, I Want To Take You Higher: The Life and Times of Sly Stone.

All that, and rolling salvos of non-lexical vocables too. Not choruses this time, and not really refrains either. The true refrain here is the title phrase, bursting out of the first verse and coming back time after time:

Hey, hey, hey, hey

Beat is getting’ stronger

Music getting’ longer, too

Music is a-flashin’ meI want to, I want to, I want to take you higher

I wanna take you higher

Baby, baby, baby, light my fire

I wanna take you higher

I want to, I want to, I want to take you higher, and away we go. Wanna take you higher, I wanna take you higher (Higher), and here we go again. It’s the verse and the chorus all in one, riffing on repeat. It’s the song’s title and its mission statement. It’s also the mainspring for the repeated interludes of nonsense syllables, always touched off by another higher:

Boom laka-laka-laka, boom laka-laka-laka

Boom laka-laka-laka, boom laka-laka-laka

Boom laka-laka-laka, boom laka-laka-laka

That’s how it goes on some online versions of the lyric sheet, at least. Whatever you do, don’t run anything through Spellcheck. It’s oral transcription, and your eardrums may vary. On this site it’s Boom shaka-laka-laka Boom shaka-laka-laka, on that link it’s Boom laka-laka-laka, Boom laka-lak-goon-ka boom. Some transcriptions pimp out the syllabics with exclamation points (Boom laka-laka-laka! Boom laka-laka-laka!), others splice in extra lexical snatches (Hey hey hey hey, Higher higher higher). Some end on running reps of higher, and some by doubling down on reps of Boom laka-laka-laka.

Yadda, yadda, yadda. Talk about talking nonsense. If you’re thinking it’s whacked to be parsing babble like this, you’re not wrong. It looks like gobbledygook on the page, because on the page it is gobbledygook. Say it out loud, and you sound like a loon. Subject it to close reading, and you’re missing the point by a continental divide or two.

Oom bop bop. Boom laka-laka-laka. Scuttle the lyric sheets. Cue up the tracks on repeat. Those nonsense syllables booming and bopping in your ear-buds have a long history and take a multitude of forms. What you hear is what you get.

That’s how it’s been since the earliest days of recorded sound. Singers of all sorts cut their vocals, and glossolalia comes with the territory. This you’ve got to hear. You tap your foot to it, and you play it back.

Boom laka-laka-laka, Boom laka-laka-laka on repeat, another catchy volley of non-lexical vocables coming through loud and clear. Only this time nothing like the ethereal vocal harmonies of “Good Vibrations,” something smacking of the revved-up verbal attack of jive-talking and scat-singing. Another head-rush of gibberish on repeat, only this time a vocal break from the beat in the midst of taking you higher. Something in the boisterous spirit of Cab Calloway’s “Minnie the Moocher” (Hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-hi Hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-hi). Something in the raucous spirit of Little Richard’s “Tutti-Frutti” (A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom). Sly keeps whooping he wants to take you higher, but his non-lexical vocables fire the booster-rockets.

Tap your foot to it, and play it all back. Just don’t ask what the A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop really means. What you hear is what you get. It comes with the territory. It makes no sense and it feels right. It makes no sense and that’s why it feels right.

If English is your mother tongue, you could say it’s bred in the bone. Something about all those Nonny-nonny-nos and Diddle-dee-dums in heavy rotation in all those old English ditties and folk ballads. Something about all those Iko-Ikos and Derry-os hoovered up from all those English-adjacent dialects lilting and diddling away. Something about English words with roots in non-semantic sounds. Lullaby, from the Middle English lollai or lullay, “probably imitative of lu-lu sound used to lull a child to sleep.” Folderol, from Fal-lal-de-ral, originally “a nonsense refrain in songs, much like tra-la-la.”

It’s a mother lode. Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay. Boola boola. Boop-Boop-a-Doop. Ob-la-di Ob-la-da. It goes in one ear and goes in the other one too. It’s as if you’ve downloaded one big maxxed-out playlist on shuffle mode. Now up, the Child Ballads: With a downe, derrie, derrie, derrie, downe, downe. Next up, Lady Gaga: Dum dum, da-di-da Dum dum, da-di-da-dadda-da-di-da.

Nonsense refrains, jabberwocky choruses. Cadenzas of glossolalia, arias of gibberish. Rapid-fire babble, non-lexical vocables. They’ve been around forever and they’re never going away. Brian Wilson struck gold, but he didn’t put the bop in the oom bop bop. Sly Stone hit the jackpot, but he didn’t put the boom in the boom-laka-laka. They were standing on the shoulders of giants, and so were the giants. One big playlist on shuffle mode, all on one bomp-bam-boom bandwidth, one Trolly-lolly-lo and Be-bop-a-lula after another.

What gives them their staying power? Musicologists have some theories. High on the list: sturdy practical utility by long social custom. On-the-job refrains in work songs and sea shanties (Hey ho rumbelow, Way-ay-ay). Expedient vocal filler for Latin-challenged church choirs (Fa-la-la-la-la). Off-the-shelf phonetic placeholders buying time for balladeers to improvise storyline verses (With my ree rum too rum | Fall the diddle i day). Readymade euphemism on tap when being explicit would kill the vibe, or you can kiss my sweet bum-bum-be-dum-bum.

Makes perfect sense, but this is nonsense we’re talking about. You can only ask gibberish to rationalize itself so much. Culture has something to say about the undying stick-to-itiveness of belted-out syllables signifying nothing, but the real secret surely lies deep in our natures. If the perennial allure of non-lexical vocables sometimes seems to be the most natural thing in the world, it must be the way we’re wired. It must mean there are times when meaninglessness makes sense like nothing else can.

Nobody knows who put the nonny in the hey nonny nonny, and we should know by now it’s a dumb question. All that’s really worth kicking around is why it was ever there in the first place and why in the world it’s still in the loop. Impossible to tell, but we can always go back to the best of all possible just-so stories. That would be the boffo little ditty from Act III of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, sung by the attendant tunesmith Balthasar at the request of his prince. It’s one for the maidens unlucky in love, taken for rides by rakes on the make:

Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more.

Men were deceivers ever,

One foot in sea, and one on shore,

To one thing constant never.

Then sigh not so, but let them go,

And be you blithe and bonny,

Converting all your sounds of woe

Into hey nonny, nonny.

Sing no more ditties, sing no more

Of dumps so dull and heavy.

The fraud of men was ever so

Since summer first was leafy.

Then sigh not so, but let them go,

And be you blithe and bonny,

Converting all your sounds of woe

Into hey, nonny, nonny.

Never mind who put the nonny in there. It’s there for a reason. It’s there for the sonics, not the semantics. It’s there to convert your sounds of woe into nonsense syllables, turning your pain and suffering into a soundtrack for being blithe and bonny. Sigh no more, ladies, here’s a mouthful of non-lexical vocables, just the thing for letting all your sorrows go. It’s all much ado about hey nonny nonny.

Sigh no more too, you gents – there’s a whole lot more Ooby dooby doo-wahs and Shang-a-lang-a-ding-dongs where those Hey nonny nonnys came from. Does it really still work, you may ask? Like a charm, going by that big old sound system on shuffle mode that keeps us coming back for more. Like nobody’s business, going by the strains of wordless earworms still breaking out all over. Going by the track record, non-semantic hooks must still have our number or else we wouldn’t be hearing a peep out of them.

It’s all much ado about hey nonny nonny, and that’s the ticket. It makes no sense, but it’s there for a reason. It means nothing at all, but it’s still just the thing for converting anything that plagues you into something that sends you. Surreal or silly, sacred or profane, it’s there to remind you that sometimes telling it like it is means letting words go. It’s a conversion experience waiting to happen.

This you’ve got to hear. Brian Wilson converting demons and bugaboos into Oom bop bop oom bop bop. Sly Stone converting bugaboos and demons into Boom-laka-laka boom-laka-laka. Leonard Cohen’s ace backup singers in “Tower of Song” going Doo dum dum dum da doo dum dum. Going Doo dum dum dum da doo dum dum in silky harmony all the way through, and on one live recording in London late in life, Cohen going out on an impromptu monologue in his hardboiled baritone that goes something like this:

Are you truly hungry for the answer? Then you’re just the people I want to tell it to. Because it’s a rare thing to come up on this. I’m gonna let you in on it now. The answer to the mysteries: Doo-dum-dum-dum-da-doo-dum-dum.

Were truer words ever spoken? You heard it from the horse’s mouth: Doo dum dum dum da doo dum dum. It means nothing and it tells you everything you need to know. What you hear is what you get. It makes no sense, but it sounds just right. It looks like Dada alphabet soup on the lyric sheet, but it’s pure poetry when voices carry. It’s the answer to the mysteries. It’s the way we’re wired.

It’s the answer to the mysteries, so don’t ask what it means. Don’t ask who put the dum in the Doo-dum-dum-dum. They’re nonsense syllables, and they’re there for a reason. They’re non-lexical vocables, and they’ve got our backs when words fail. They’re giving us good vibrations. They want to take us higher.

Many thanks, Mary! So good to hear it touched a chord. The Leonard Cohen clip is my all-time fave!

Cheers,

David

Brilliant piece, David! Thanks for the music clips to illustrate your thesis. I’m going to enjoy going through this many times over.

Mary Berg