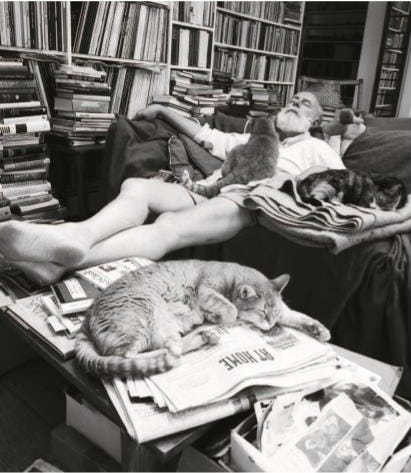

The centenary tributes for black-humor past-master Edward Gorey (1925-2000) have been dropping thick and fast, bless them. Keep them coming, I say. Gorey’s undying cult status was sealed in indelible ink by his mock-macabre animated title sequences for the PBS Masterpiece Theater Mystery! series launched in 1980, but as any obsessive will tell you, that scarcely begins to scratch the surface of the sui-as-generis-gets glory that is Gorey.

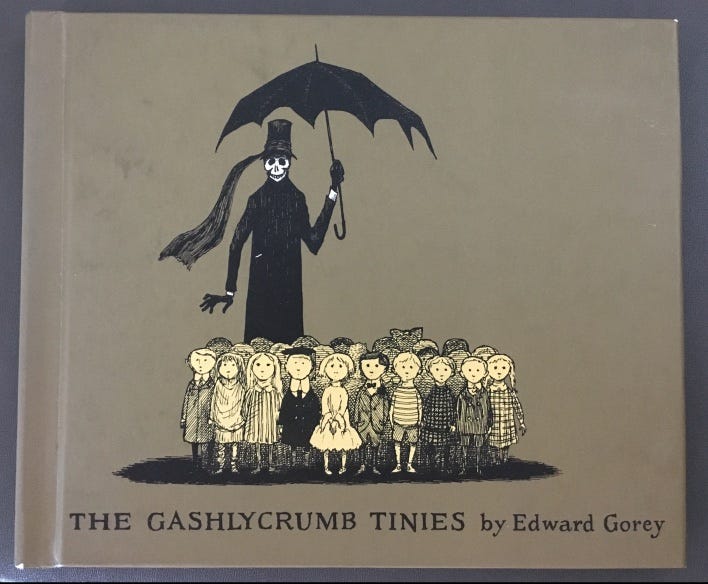

Like many a counterculture kid, it all started for me with The Gashlycrumb Tinies. All the anecdata agrees – it’s the gateway Gorey of choice bar none. If it doesn’t get you hooked, nothing will.

Full title: The Gashlycrumb Tinies: or, After the Outing. First published in 1963 by Simon & Schuster as the first third of the slipcase collection The Vinegar Works: Three Volumes of Moral Instruction. It was Gorey’s eleventh book of his curiosity-cabinet writing and art, a growing body of work already hailed by literary critic Edmund Wilson as “a whole little personal world … at the same time poetic and poisoned.”

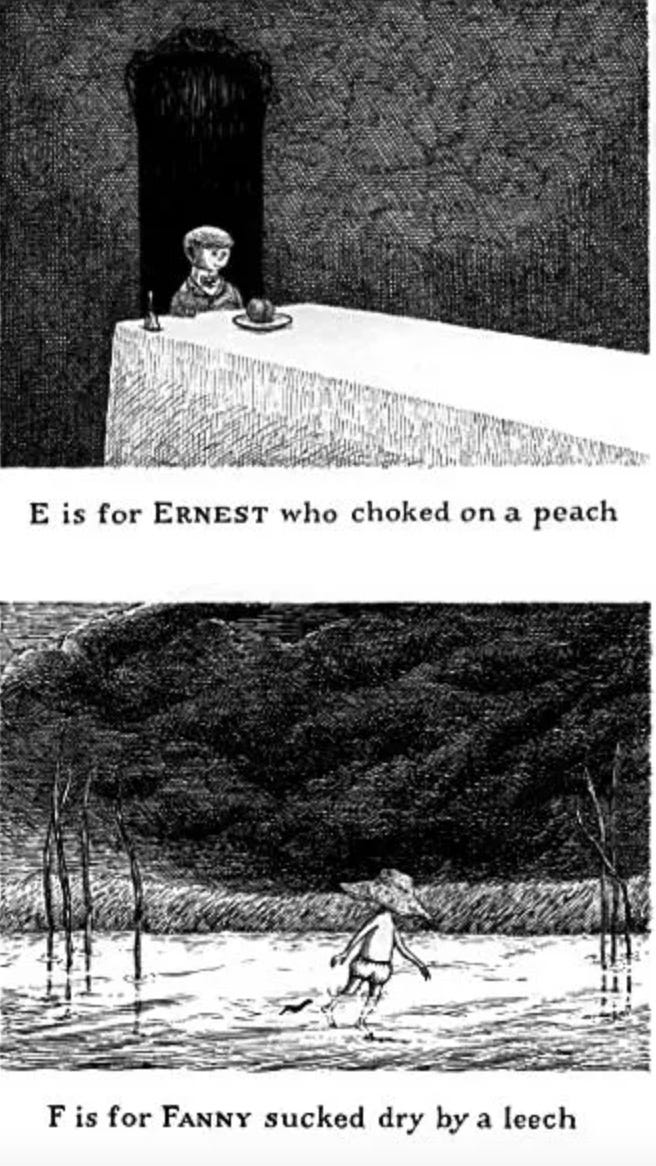

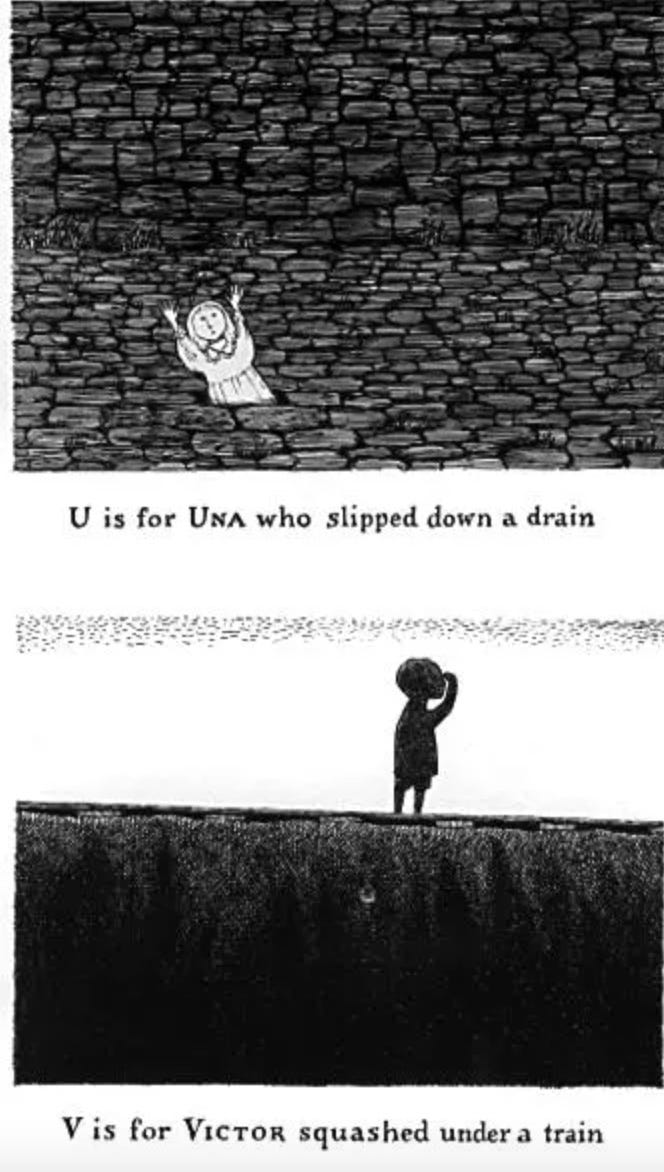

That just about covers it, and in this case it’s the perfect tagline. Poetic: the text consists of thirteen rhyming couplets in adept dactylic meter, each couplet spotlighting two pitiful waifs by name. Poisoned: every last line delivers the curtest of obits on the untimely end of each tot in turn.

It’s black comedy of the deadpan kind, morbid farce with a straight face. It’s a whole little world of airtight ghoulish wit, a custom-made staging ground for Gorey’s lapidary brand of fiendish surrealist nonsense. Not one grownup in sight, unless you count the towering skull-faced avatar in Victorian undertaker threads on the cover, looming over a gaggle of pipsqueaks with a giant bat-wing brolly. Two captioned images per page, etched with a pen dipped in arsenic. One terse line for each darksome drawing, each line an obit for one more doomed urchin.

It’s a package deal, and that’s the kicker. You know right away what’s going down – Gorey will be doling out death sentences to 26 little ones in time-warp period garb, first name by first name, letter by letter. It’s an ABC book. It’s a danse macabre in the form of an abecedarium.

Not a term you hear every day, but if you’re reading this you know what it means. Abecedarium, from the Medieval Latin abecedāriānus, coined by none other than St. Augustine. A derivation of the English word “abecedarian,” meaning “one learning the letters of the alphabet” (noun) or “pertaining to the alphabet, alphabetical” (adjective). The noun “abecedarian” in due time giving rise to the term of art “abecedarium,” an acrostic verse form calling for successive lines or stanzas beginning with letters in alphabetical order. Another word for it is abecedary, but by and large A is for abecedarium.

Fancy name, familiar thing. Bet you remember a favorite version right off the bat. It’s how we all learned our ABCs, the primary-color troupes of cosplay letters parading by page-by-page in alphabetical order. A is for Alligator, B is for Buffalo. A is for Apple, B is for Bread. X is for Xylophone, Y is for Yarn. It’s how we’ve all learned our ABCs for ages now.

You don’t really have to sweat the Latin, but it keeps things interesting. It’s not as simple as ABC. Not all ABC books are abecedariums, and not all abecedariums are manuals for your ABCs. The earliest examples go back to antiquity, beginning with the Hebrew Bible. (Psalm 119, notable as the longest psalm, is the longest because it’s an acrostic poem with 22 stanzas tracking the 22 letters in the Hebrew alphabet.) Chaucer wrote one when he was up and coming – “An ABC (The Prayer of Our Lady)” – complete with an epigraph in Latin that left nothing to chance. Incipit carmen secundum ordinem litterarum alphabeti, right there at the top: Here begins the song according to the order of the letters of the alphabet.

Here begins the saga of the abecedarium in Middle English, and it was just getting started. ABC primers in rhyming verse came later and have their own illustrious history. They would be some of the first printed matter solely for schoolchildren. It was the way you would learn to read, starting with your ABCs.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. In the early days there was only room for the bare-bones letters on the single folios affixed to a paddle-like hornbook or battledore, but with the influx of bound pamphlets and booklets, the familiar paginated format now familiar to us all came of age. ABCs spelled out in pictures and captions. Letters brought to life. Abecedariums proper, neat short rhymes beginning with each successive letter in alphabetical order.

A is for Axe, B is for Bull, and so on, each with its own beguiling etching or woodcut as a visual aid. And sometimes a whole little story, a winsome alphabetical tale or chronicle. Like that famous saucy one with the wacky stemwinding title first printed in London by John Evans, circa 1795: The Tragical Death of a Apple-Pye, Who Was Cut in Pieces and Eat by Twenty Five Gentlemen: With Whom All Little People Ought To Be Very Well Acquainted. It’s a literary genre unto itself, a prolific lineage stretching from assorted Anons to Kate Greenaway and Dr. Seuss, et al.

Up they’ve kept cropping like fairy rings of fungi. Not all of them by-the-book abecedariums, some of them abecedariums by default or afterthought. Some more deft or daffy than others, some straitlaced and others downright cheeky, but no matter. The cornerstone conceit remains the same.

They’re books for nippers. They aim to instruct by way of delight. You’re learning to read. You’re cracking a code. You’re having a ball.

Or maybe not. I give you The Gashlycrumb Tinies. An ABC book with a body count. Tykes dropping like flies.

It’s all a spoof. Or maybe a sick joke. Some gentle souls sure must have felt that way when it first came out in 1963, insolently billed as one of Three Volumes of Moral Instruction.

The same year, as it happens, that not everyone was quite ready for Maurice Sendak’s game-changing Where the Wild Things Are. You could call it a volume of moral instruction too, and it got some grownups freaked out. A picture book with a wild child in a wolf suit on a wild rumpus as hero? A boy who would be king of the Wild Things with their terrible claws and terrible teeth? Too scary, too raw, too wild by half. Books for bambinos shouldn’t get under the skin like that.

Maybe that’s why Gorey gets a pass. It’s not bloody likely that most folks take his death-trap ABC book as the real thing. He’s not really getting off on creeping out actual children by dispatching his inky-dink moppets with no mercy. It’s a burlesque, a send-up, an impish little piece of gallows humor. It’s all in wicked good fun and if it’s not to your taste, that’s between you and your consenting adulthood.

But what if he’s having it both ways? It wouldn’t be the first time a parody of pedagogy went for the jugular. It would hardly be the only time a crack wit wielded lethal caricature as a corrective to cloying portrayals of childhood. Besides, you’d have to be born yesterday to believe there was ever a time when ABC books were only teaching you the ABCs.

Gorey isn’t just being facetious in calling his abecedarium a volume of moral instruction. He’s getting a kick out of playing possum with the elephant in the room. Strange as it sounds, alphabets have always had agendas. They come with strings attached. For as long as reading primers have been around, there’s been an eternal wrangle over the lessons you ought to be learning as you’re learning your letters.

Alphabets have always had agendas, and they’ve been known to spell out doctrines. History teaches us the stakes go up whenever the vessel of moral instruction takes the form of a full-blown abecedarium. You can’t get anywhere with a versified alphabet in a neutral gear. It’s telling a story and calls for a through-line. It’s an initiation and it’s sending a message. The letters and the lessons are in it together.

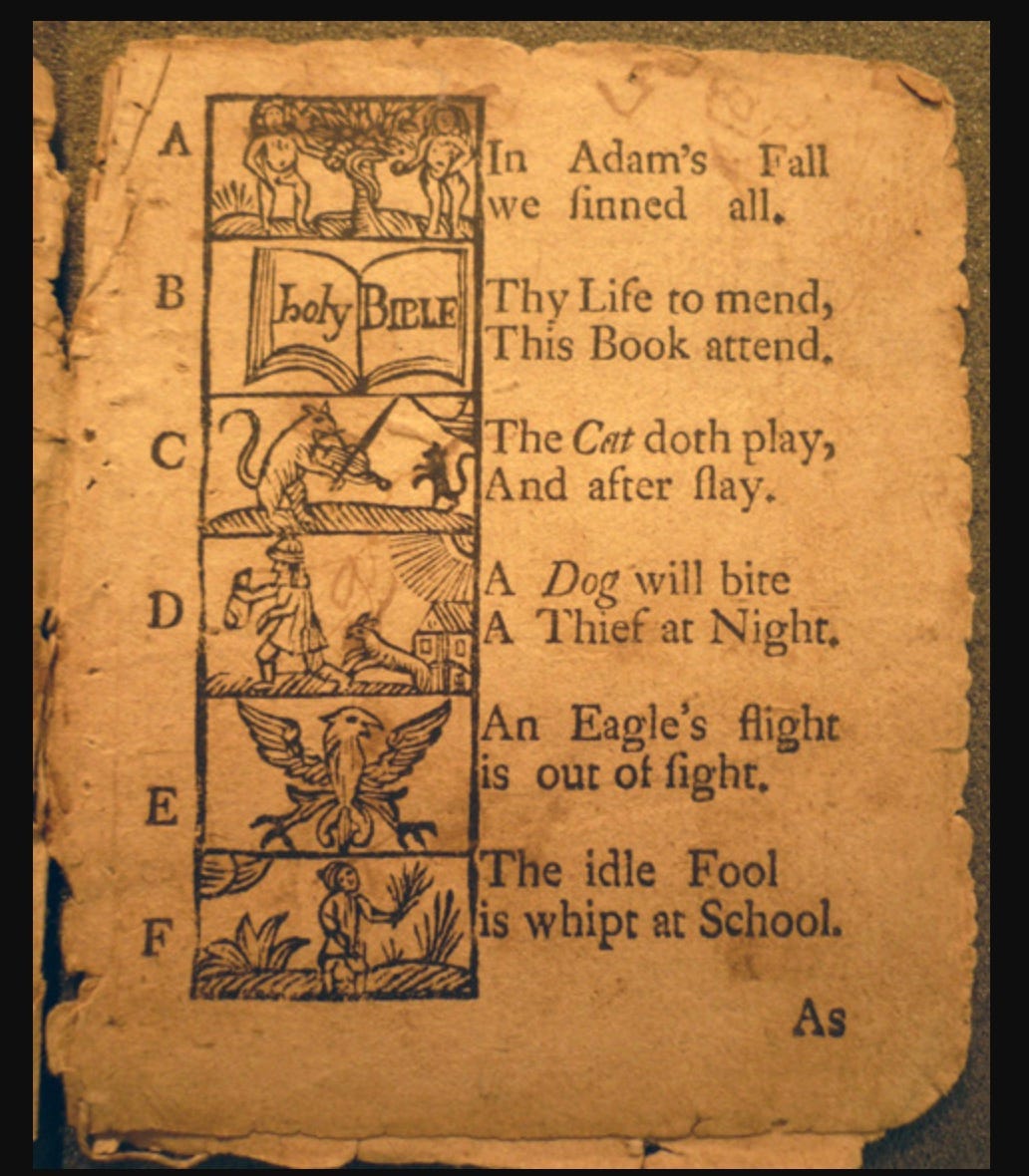

It’s been that way from the beginning. A pictorial ABC in rhyme calculated to sow fear and dread in the hearts of little first readers sounds like a taboo going smash, but it turns out to be the oldest trick in the book. It’s not a sick joke or iconoclasm incarnate. It would be a fair description of the first and foremost American abecedarium of them all.

I give you the opening pages of the late great New England Primer. The rock on which the Puritan schoolroom was founded. First printed in Boston circa 1690 and then in copious editions thereafter, For the more easy attaining the true reading of English. It begins with the alphabet. It begins with an illustrated abecedarium.

To say the Primer was far and away the standard textbook of its day is to undersell its dynastic reign of influence. As Patricia Crain writes in her first-rate scholarly survey The Story of A (2000), we’re talking about “one of the longest-lived and most successful literacy manuals in history,” with some estimated eight million copies in print through the early 19th century. Long after the Puritan theocracy melted away, The New England Primer still ruled the roost. It was the alpha and omega of the colonial American schoolhouse.

Editions abounded, but there was one constant. The ABCs came first. You had to get those down if you were going to keep turning pages. You were expected to memorize them by rote, and the verse inscriptions were meant to stick in your head.

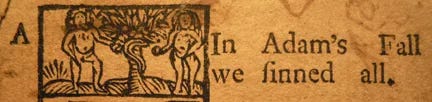

It all begins here, Crain makes plain, with the book that “inaugurates American alphabetization.” From edition to edition some of the rhymes would change, but not the very first one. Not the inscription for A. The first verse meant to stick in your head was always the same:

Two lines, six words, seven syllables. Not much room to work with, but did it ever fit the bill. A wasn’t for Adam, A was for Adam’s Fall. The whole Old Testament doctrine of Original Sin in one pinpoint rhyming couplet. It was time to memorize your ABCs, and you were expected to recite the verse out loud so it would stick with you for good.

You already knew the story. You had heard it before in sermons. Now it was time to get it by heart. You were learning your alphabet and your scripture in the same breath. You were just a schoolchild, but your soul was in peril. You were born into sin. You too were fallen.

And that was just the letter A. None of the other inscriptions are quite as letter-perfect as a concentrated hit of catechism, but the alphabetical drumbeat of puritanical admonition rolls on. It’s not nonstop doom and gloom – L is for both peaceable creatures in the couplet The Lion bold | The Lamb doth hold, and the Lion laying an avuncular paw on the Lamb’s hindquarters is a nice feel-good touch – but it’s the letters belching brimstone that jump off the page.

Here’s G in the guise of a gigantic hourglass on its own theater proscenium, half-full or maybe half-empty: As runs the Glass, | Man’s life doth pass. Here’s T taking a lusty swing with a scythe, an allegorical harvester grimly reaping away: Time cuts down all, | Both great and small. And how about Y, a strapping skeleton about to run through some mouthy Everylad with a big-ass lance: Youth’s forward lips | Death soonest nips.

It’s not looking good for the forward Youth, and it doesn’t look like the punishment fits the crime. Nipped in the bud just like that for backtalk or whatever? Those Puritan schoolmasters were tough customers, but still.

Then again, it’s not like our wayward Youth wasn’t put on notice. He would have learned to recite his ABCs by rote, beginning with the verse inscription for A. He should have known he was damaged goods from the day he was born. In Adam’s Fall, goes the verse, We Sinned all.

All of a sudden Gorey’s alphabetical postmortems don’t seem particularly skeevy after all. His cold dead cherubs aren’t poster children for perdition. They’re rubbed out one by one, but they don’t go to meet their maker. They don’t fall prey to Satan’s snares. They aren’t born sinners. They have nothing to repent. They’re just unlucky little buggers.

That doesn’t mean there’s no takeaway. As the morgue piles up with deceased young things, you get the sneaky feeling that Gorey’s abecedarium might be laying down a marker. It’s a system of order by nature, and there seems to be the semblance of a storyline.

Not to say it’s not what it looks like. Not to suggest it doesn’t quack like a duck. It’s not an alphabet on the up and up, not even close. It’s all parody and no pedagogy. All letters and no lessons. It’s not really for learning your ABCs, squirts.

All I’m saying is Gorey is having it both ways. He’s not pretending his primer is legit, but he’s not contriving to make a complete charade out of it either. It’s not pastiche and it’s not sabotage. It’s not an actual ABC book, but it’s a bonafide abedecarium. He’s twisting the genre all out of shape, but he’s also exposing its inbred quirks and kinks. He’s not clapping back at the Puritans, but he’s not letting them off the hook either. He’s playing a parlor game and he’s taking a stand.

Poetry and poison, just as Edmund Wilson noted with approval back in the day. Poetry: thirteen rhyming couplets in nimble dactylic meter, each couplet profiling a pair of small fry in alphabetical order by first name. Poison: each line a laconic obit in calligraphic longhand under a crosshatched penny-dreadful sketch, one by one a thumbnail coroner’s report on the ill-fated demise of each rug-rat in turn.

It’s a tour de force of playing both ends against the middle. The Goreyfied couplets toggle between the lurid and the ludicrous, just as the spidery drawings seesaw from grisly to zany. It’s biting satire, letter by letter. It’s a tongue-in-cheek sendup, from A to Z. It’s an abecedarium that doesn’t put a foot wrong, and it’s an abecedarium with a body count.

Be afraid, kiddos, be very afraid. It’s a thin pen-and-ink line between tragedy and comedy. There’s no moral calculus here, and that’s the message. You need to learn that life and death can be capricious. You slip down a drain or you’re squashed under a train. Life is short, and then you die. You’ll never get out of this world alive.

Pretty edgy, plenty campy, yet in the end still true to form. Patently its own screwball crypto-steampunk thing, but it doesn’t come out of a vacuum. A running gag in cold blood, but also a knowing bow to the ABC family tree.

It all goes back to the New England Primer. It begins with the English alphabet in teeming circulation across generations, cunningly assembled as a catchy abecedarium. Little pictures alongside the little verses, because its little readers are still illiterate.

But not for long, not if the abecedarium does its job. It’s here to help you commit your ABCs to memory. It’s here to teach you your letters and your lessons in one fell swoop. It’s an abecedarium, which is to say an alphabet with a through-line in verse. An abecedarium, which is to say an alphabet that acrostic energy and poetic ingenuity built.

We don’t learn our ABCs by reciting verses by rote anymore, but Edward Gorey is here to remind us that the alphabet left to its own devices might as well be a blank slate. He’s here to tell us that A is for Abecedarium. He’s prising the template apart and putting it back together again. He’s watching his Ps and Qs and he’s getting away with murder.

It’s farce and it’s more than just farcical. It’s not an alphabet to get by heart, but it’s an abecedarium to conjure with. It’s parody, it’s black comedy, it’s all in jest, it doesn’t go on the children’s shelf. It’s misanthropy without apology, it’s in your face, it’s making a contrarian mockery of the old-school alphabet primer as an underpinning of a kid’s moral education. Gorey is having it both ways, and that means we can too.

Lapsed children, today’s takeaway is that the alphabet is an abecedarium waiting to happen. A primer with no X factor will only take you so far. A is for Arbitrary until Artifice steps in, and that’s when literacy literally has its say. You don’t really know your ABCs unless you know how to make the alphabet dance to your tune.

Edward Gorey at 100 hasn’t lost a step. Class is not dismissed. He’s still got a thing or two to teach us about the tricks of the trade in spirit and letter.

A is for Alphabet, but you’d better have a Plan B.

A is for the Art of taking poetic liberties with alphabetical order.

We’ve come a long way since Adam’s Fall.

A is for Abecedarium.

The Edward Gorey House is now a museum open to the public (2025 season begins April 10).